Study On COVID-19 Testing Data Calls For Random Testing, Improved Data Quality

Jaipur and Delhi: Data on exposure to COVID-19 were missing for 70.6% of patients tested between January 30 and April 30, according to a new study by government and independent researchers. This could be due to unknown COVID-19 cases or due to poor contact-tracing and data collection, the study said, adding that this lack of data restricts the ability to understand the spread of COVID-19 in the community.

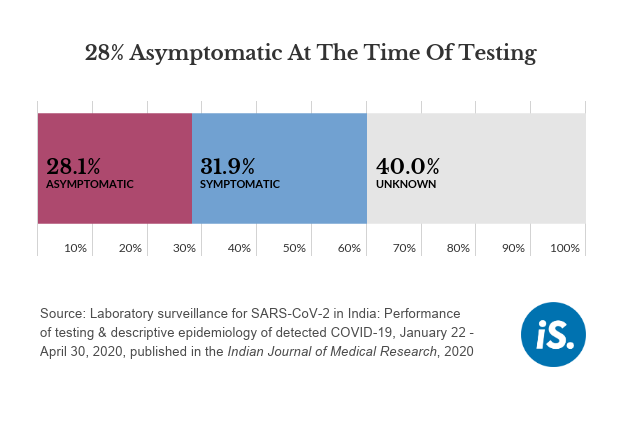

As many as 28% of those who tested positive for COVID-19 between January 22 and April 30 were asymptomatic at the time of sample collection, found the study by researchers from the government’s Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the public-private Public Health Foundation of India and independent consultants.

As many as 67% of all tests were among men, compared to 33% among women and there were more cases per million among men (41.6 per million) as compared to women (24.3 per million). But a higher proportion of women who were tested were positive (3.8% vs 4.2%) for COVID-19, the study found.

The study analysed data from 1,021,518 tests and 40,184 COVID-positive patients from 456 testing centres that used the real time-reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) test. Overall, it suggested that the government must increase contact-tracing and testing, and improve the quality of its data.

Importantly, it says India must supplement laboratory testing with sentinel surveys (random testing in specific communities) to improve its pandemic response. There is no nationwide sentinel testing so far, even though it could provide early warning signs and information about the next stage of the pandemic, and has been recommended by several health bodies including the European Center for Disease Control.

In India, Kerala has begun sentinel surveys for healthcare workers, those with high social exposure such as delivery staff, migrant workers and epidemiological samples from hospitals. Countrywide, all patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARI) have to be tested.

More local decisions needed

By April 30, 99% of 736 districts in India had tested for COVID-19 and 71% had confirmed cases, the study said.

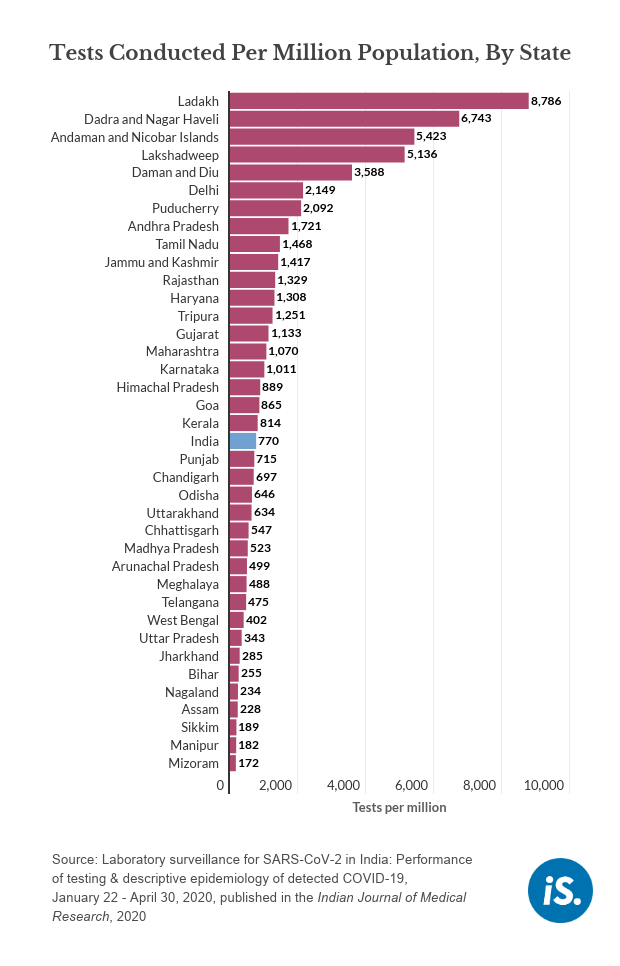

But the rate of testing varied from 172 tests per million in Mizoram to 2,149 tests per million in Delhi.

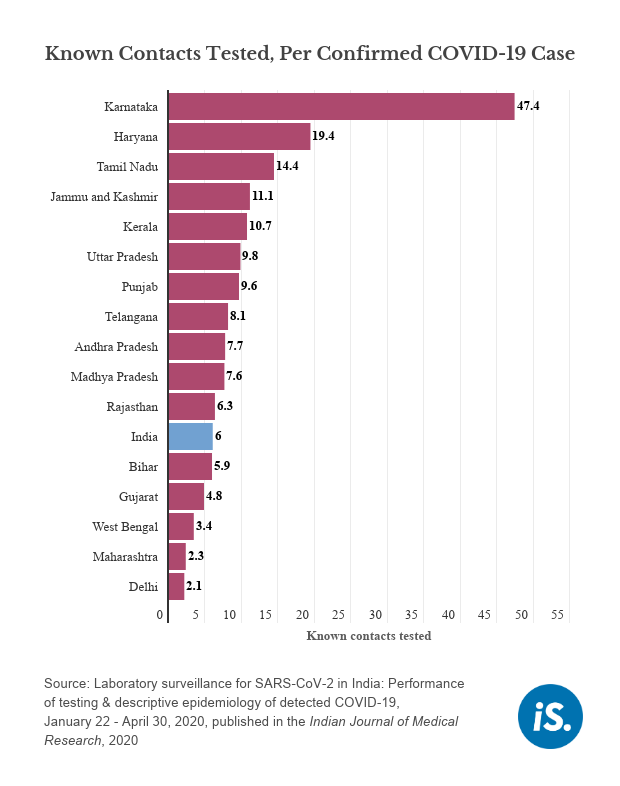

Not just the testing rate, but the number of contacts tested for each confirmed case also varies across states.

“It’s time to talk about each state or district and not the whole country as there are different levels of the epidemic and contact-tracing in different states,” said Tarun Bhatnagar, from the ICMR School of Public Health and one of the authors of the study.

These numbers only take into account 29.4% of people tested, as for the other 70.6%, there are no details on whether they were family members or contacts of confirmed cases, the study said.

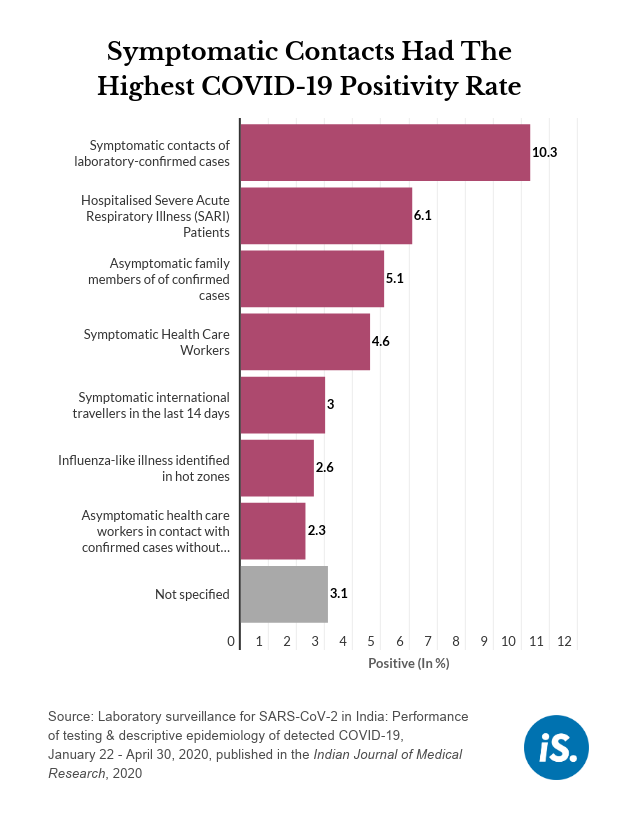

Even though 28% of patients were asymptomatic at the time of testing, “the focus still has to be on finding symptomatics as the positivity ratio is highest for that category”, said Bhatnagar. For instance, 10% of symptomatic contacts of confirmed cases tested positive as compared to 5% of asymptomatic family members, the data show.

Asymptomatic patients could have developed symptoms as the disease progressed but data on that were unavailable.

States should test all SARI patients

About 10% of all COVID-19 cases were among those who were hospitalised because of SARI, the study found, equivalent to the proportion of symptomatic contacts of patients and more than any other category of patients.

The COVID-19 specimen form has several categories for patients and the person collecting the specimen has to fill out such a form for every patient.

About 6% of all SARI patients tested were positive, the second-most after laboratory contacts of confirmed cases. “The SARI positivity rate is relatively high which could be because of a high numerator, that is a lot of SARI patients are COVID positive or, because of a low denominator, which would happen if states are not testing all SARI patients,” said Bhatnagar. “All states should be testing all SARI patients,” as this helps understand the spread of the disease, he added.

Of all those who tested positive, 55% were international travellers, contacts of confirmed cases, healthcare workers, those with influenza-like illnesses or those with Severe Acute Respiratory Illness (SARI). Such information was not available for the remaining 45% of patients, said the study.

Not only the elderly, young adults are also susceptible to COVID-19

Patients in the 20-49 age-group accounted for 59.3% of total cases and 64.9% of tests, indicating that young adults are also susceptible to contracting the virus, Bhatnagar said. Those older than 50 years comprised 29% of cases and 22.5% of tests.

The youngest are the least susceptible to the illness, based on the number of cases per million in at-risk populations across age groups, the study found, with cases detected per million increasing with age. There were fewer than 13 cases per million in those below 19 years, 40.5 per million for those aged 20-29, 48.5 per million for those aged 30-39, 50.1 per million for those aged 40-49, and 64.9 per million in those aged 50-59.

While the young are susceptible to contracting the virus, not all patients develop serious symptoms. Individuals with comorbidities and the elderly face significantly greater risk of death from COVID-19, as IndiaSpend reported on April 6, 2020.

Lack of data

All the findings from the study are based on the limited data available. For instance, because of the testing criteria, except for international travelers, SARI patients and those with influenza-like illnesses, anyone else would require exposure to a positive case before they can be tested, which means that the data would be skewed towards symptomatics and contacts of confirmed cases.

Even in contact-tracing, the exposure history of 70.6% of patients was missing.

Such limited data hinder researchers’ ability to calculate the probability that household members or close contacts of confirmed cases get infected.

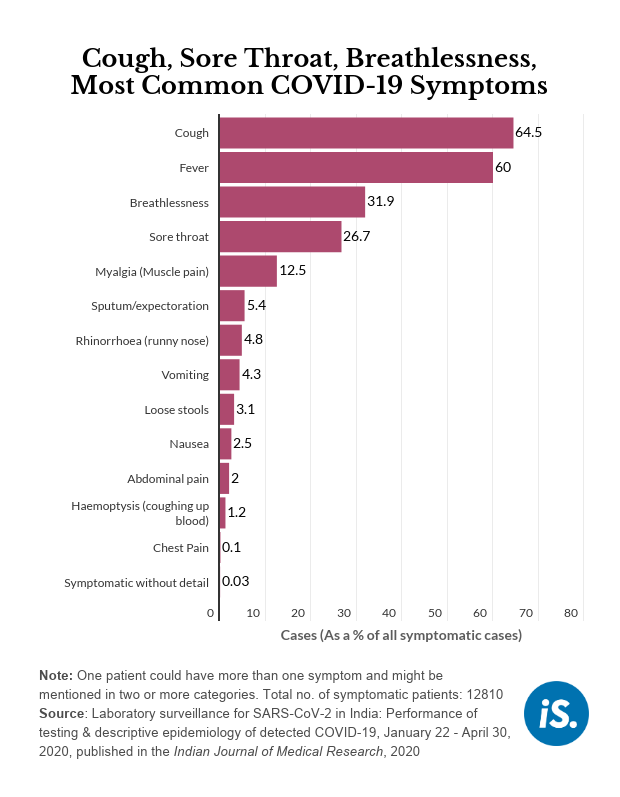

Further, the specimen form might not have all the options that patients fit under. For instance, those taking the sample choose the symptoms the patient has from a list of symptoms already on the form. There is no option to enter the symptoms of loss of smell and taste on the form, so many might not mention this, Bhatnagar explained. This would result in an incomplete profile of patients’ symptoms.

These gaps in data are partly because data are collected by laboratories testing for SARS-CoV-2 through a specimen form and the person taking the sample might have too many patients to take a complete history from each, said Bhatnagar. “As tests increase, the proportion of patients with information missing might remain the same or be even higher,” he added.

(Khaitan is a writer/editor and Bharadwaj is an intern with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.