How Once ‘Backward’ Idukki Is Leading Kerala And India In Ending TB

Idukki, Kerala: In 2006, Idukki was the worst performing district in tuberculosis (TB) control in Kerala. The scenic hilly district, famous for its tourist destinations of Munnar and Thekkady, has difficult terrain and relatively poor public healthcare systems.

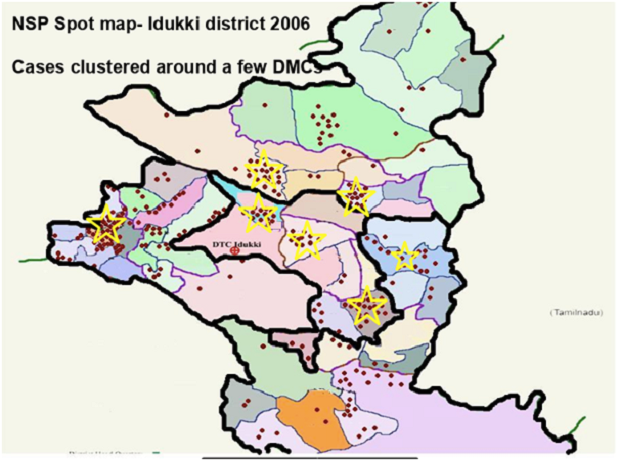

The district was detecting only 17 TB cases per 100,000 population at the time, which, as per the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP), was below expectation. RNTCP expected about 50 cases to be picked up per 100,000 people in south India.

In 2006, however, the District TB Centre decided to fill all vacancies of medical officers and laboratory technicians in order to improve access to diagnosis and treatment. It also started proactively looking for TB cases--an exercise called ‘active case-finding’, started nationwide in 2017--as far back as 2006.

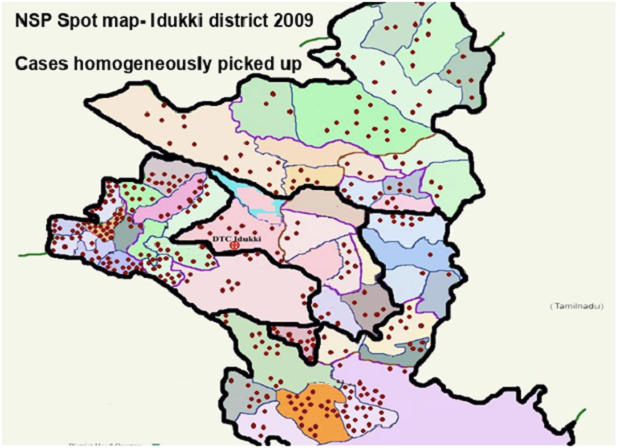

This led to an initial spike in the number of cases detected until 2009, after which the number has steadily fallen to now stand at just 51 for 100,000 people, as per the District TB Centre. India’s TB detection rate (or incidence), by contrast, is estimated to be 138 cases per 100,000, as per 2017 RNTCP statistics.

This shows how simple improvements in the public healthcare infrastructure and its utilisation can help India’s anti-TB efforts. Idukki is now one of the five districts with the lowest incidence of TB that have been selected by the Central TB Division, which implements RNTCP, to roll out strategies to cover the last mile of TB elimination, bringing incidence down to one case per million.

“Idukki is the laboratory where we tested all our ideas,” said Shibu Balakrishnan, the World Health Organization (WHO) consultant for the state, who has worked closely with the deputy district medical officer, Suresh Varghese, with whom he shared a strong motivation to make a difference, attesting to the effectiveness of a motivated workforce in achieving results. “Whenever any new strategy has to be tried in Kerala for TB control, it is usually tried first in Idukki, before it is implemented throughout the state.”

IndiaSpend is tracking Kerala’s ambitious plans to reduce the number of TB cases to 2020 by 2020, and deaths to zero, in a four-part series. In this second part of the series, we examine how the strategies deployed in Idukki district are key to understanding the means of eliminating TB in hard-to-reach areas, particularly where prevalence is low.

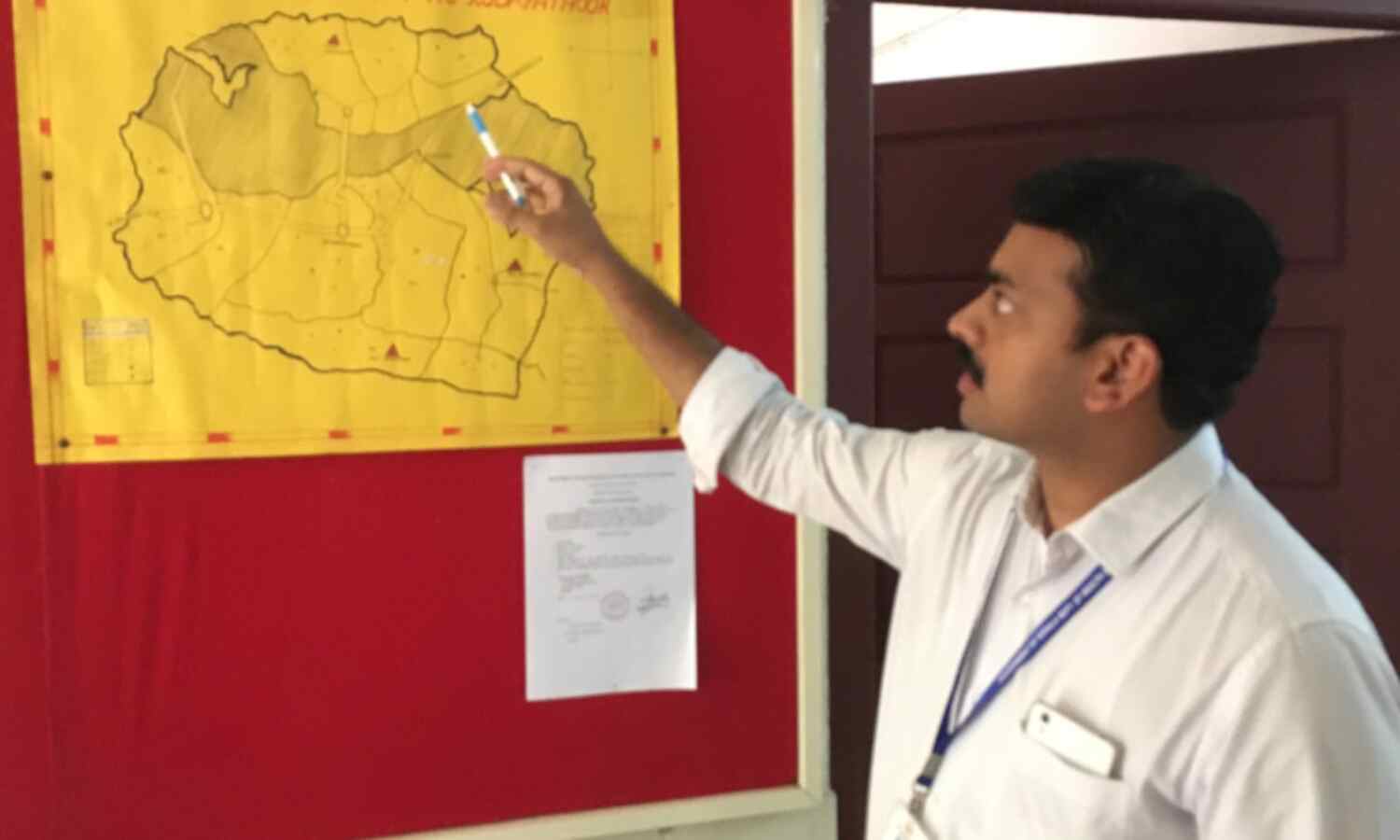

Suresh Varghese, deputy district medical officer of Idukki, showing the records collected during vulnerability mapping in the district.

Worst to one of the best

Idukki district has historically had poorer government healthcare infrastructure than the rest of Kerala--for instance, in 1995, it had 93 beds in government hospitals per 100,000 population, against Kerala’s average of 143. In 2013, government records show, Idukki had the fewest doctors (177) and fewest beds (1,085) as compared to other districts of Kerala.

It is one of the few districts in Kerala without a medical college or a tertiary public hospital, so that for serious ailments that need superspeciality treatment, such as a cardiac arrest, a patient has to travel more than 100 km to Kochi city.

“We do not have a neurologist in the district, even in the private sector. We have a couple of cardiologists in the private sector,” district TB officer Anoop K. told IndiaSpend. “Recently I had to arrange a neurologist from outside the district to be part of drug-resistant tuberculosis review meeting where we evaluate all patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis and approve treatment.”

In 2006, Idukki was struggling with a severe human resources crunch in its public health institutions. Although 21 centres (mostly primary health centres) had equipment to conduct sputum microscopy, the basic TB test in which the laboratory technician looks for TB bacilli in a patient’s sputum, only five were being utilised to full capacity, Varghese told IndiaSpend.

“The laboratories were not functional either because the medical officer or a laboratory technician was not posted there,” Varghese said.

As a result, the district was testing samples of 500 TB suspects per 100,000 people in a year. Over the next few years, the district administration filled the vacant posts. More samples began to be tested, and by 2015, close to 1,400 samples per 100,000 population were being tested annually. The national average now is approximately 700 samples.

“Now the vacancies are more or less filled. Doctors are willing to be transferred here after road access has improved,” Anoop said.

In November 2017, the state government conducted a pilot door-to-door survey of the entire population of Kudayathoor panchayat in Idukki to look for people with TB symptoms and map TB vulnerability, particularly diabetes. This exercise was then repeated all over the district and then the state.

A mapping of testing centres reporting TB cases showed they were spread homogeneously across the district, showing more uniformity of access. “The spread of microscopy centres had a huge impact in a hilly area like Idukki where people must travel longer hours,” said Balakrishnan. “These patients could have otherwise gone undetected or died.”

Source: Idukki District TB Centre/WHO

The District TB Centre was keen to have even more microscopy centres, but RNTCP guidelines said the district could only have 24 posts of laboratory technicians.

Varghese decided to use the funds allotted for partnering with the private sector to create more laboratories and hire more technicians. The District TB Centre signed a contract with the Indian Medical Association (IMA), the largest doctors’ organisation in India, to run laboratories and hire technicians. This ensured that 10 more laboratories in the district were up and running. The centre also started to pay per case for testing using microscopy, X-ray or CT scan at private hospitals.

The district now has 51 microscopy centres, including seven in the private sector.

Further, all samples that test positive in sputum microscopy in Idukki (and Wayanad district) are being sent to the Intermediate Reference Laboratory in Thiruvananthapuram, accredited by the Central TB Division, to run drug susceptibility or resistance tests. The idea is to nip any cases of drug resistance in the bud.

Patient-centric care

To strengthen the public healthcare system, health staff including front-line Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), multipurpose workers and nurses were given regular training.

The highest ranges in the district are populated by migrant workers, who would travel to the neighbouring districts in Tamil Nadu to find seasonal work every year. The District TB Centre decided to conduct active case-finding among them in 2006.

“We appointed supervisors of these workers as link workers,” Balakrishnan said. “They helped in collection of sputum samples and handed them over to our multipurpose workers. These workers would carry samples in their pockets and take them to microscopy centres.”

These activities increased patients’ access to TB treatment; they would ordinarily have delayed visiting a health institution when they were sick. The effort was to make the approach as patient-centric as possible, even training frontline health workers to have the same approach, Varghese said.

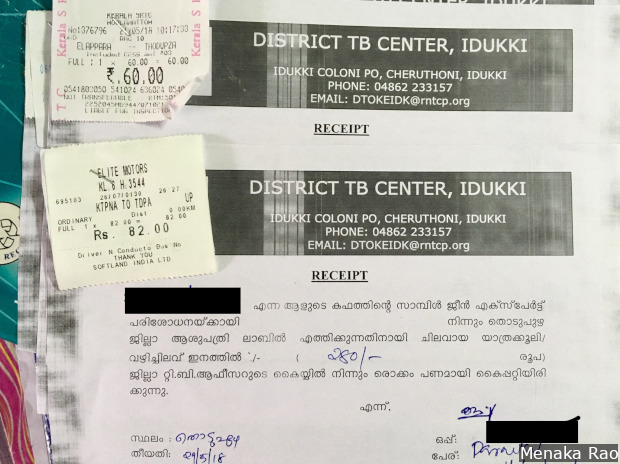

Idukki district reimburses bus fares of TB patients who travel to hospitals far from their homes.

Private doctors give government medicines

As early as 2006-07, Varghese and his team networked with the private sector extensively, asking them to collaborate with the district administration to report TB cases and training them in giving appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

The private sector in Idukki, by and large, consists of charitable hospitals and a small number of private doctors. The private doctors were sceptical at first, wary of government interference in their work. But the District TB Centre assured them that collaborating with the RNTCP would not cost them their patients but would actually benefit them by ensuring that patients completed their treatment regimens under close observation of a Directly Observed Treatment Shortcourse (DOTS) provider appointed by the government.

The government does not insist that patients go to government hospitals for follow up. “We do not want to interfere with the patients’ choice,” said Varghese. “Our concern is that the patient takes standard treatment for six months and gets our required outcomes,” that is, gets cured.

Last year, approximately 20% of the total reported TB cases in Idukki came from the private sector, Varghese said. “There are still a few doctors who do not notify [report],” he said, “There are about 10% more notifications we need from the private sector [based on drug sales]. We aim to plug the gap by this year.”

Fall in cases from 2009

With widened screening, the number of TB cases in Idukki steadily rose from 2007 to 2009. In 2007, the district detected 644 cases, a rate of 58 per 100,000. In 2009, the number had risen to 747, approximately 67 per 100,000, according to the Kerala TB Elimination Mission strategy document.

After 2009, the number of cases fell steadily--on average, by 4% every year, the District TB Centre statistics indicate (see table). In 2007, about 24 presumptive TB cases were needed to confirm a single TB case; the figure had gone up to 84 in 2016.

“Increasing coverage of TB services, strengthening of health systems and maintaining it is Idukki’s success story,” said Balakrishnan. “We have managed to keep everybody in place,” he said, referring to lab technicians, doctors and health workers, all of whom have been trained regularly. “These activities helped bring down TB notification,” he said.

With India’s new TB elimination plan--to reduce the number of cases to one in a million by 2025--there is a renewed focus on Idukki. It has shown that even in places with low resources, patients’ access to diagnostics and treatment can be improved. It also illustrates how low incidence areas, even in difficult terrains, can improve outcomes.

“When you put in resources where caseload is high, you throw a net, you can catch lots of birds,” Balakrishnan said, “In a low prevalence setting, you may need more resources as you may have to go to places where the cases are. Even if a single guy is vulnerable and gets TB, he could die.”

And Idukki has shown it can be done.

This is the second of a four-part series. You can read the first part here.

Next: In One Kerala District, A Community Group Supports TB Patients At No Cost To Govt

(Rao is a an independent journalist based in Delhi.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.