How Jharkhand's Rich Households Corner Power Subsidies

New Delhi: Well-to-do households in Jharkhand get over twice the amount of power subsidies that poor households receive, says a new study that surveyed over 900 households in rural and urban areas. Flawed subsidy design enables more affluent homes to benefit more by using more electricity.

This problem is not unique to Jharkhand and could be common in all states that have similar power subsidies, it suggests. Restructuring and improved targeting can help free up more than Rs 300 crore for Jharkhand, and a good portion of the Rs 110,391 crore ($15 billion) for all states, six times more than the 2020 budget estimate for the Union Ministry of Power.

Jharkhand’s electricity consumers received a total subsidy worth Rs 1,250 crore ($170 million) during April 2018-March 2019 (or financial year 2018-19). In both rural and urban areas of the state, the richest two-fifths of the households surveyed received at least 60% of these subsidies, while the poorest got 25%, found the study by two think-tanks, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) and the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP), released on October 2. “This doesn’t make sense--there’s an opportunity to improve equity here,” said Shruti Sharma of IISD and a co-author of the study. “Energy access is vital for development, and subsidies are provided so that electricity is affordable. But our research shows that it’s the poorest who are receiving the smallest benefits.”

While this imbalance in power subsidy distribution has been discussed in earlier studies (here and here), there has been little recent research “on the distribution of existing subsidies and exactly how targeting could be implemented to impact this subsidy distribution”, says the study. The report seeks to fill these gaps using the survey data collected from Jharkhand.

Jharkhand offers electricity subsidy to all the households across wealth quintiles. Though the amount of subsidy, by design, decreases as the average electricity consumption goes up, rich households still get some subsidy.

For example, the state government pays Re 1 per unit (1 kilo-Watt-hour or kWh) as subsidy to households that consume an average of over 800 units of electricity a month, but 63% of households surveyed in the study consumed no more than 100 units a month. Thus, rich households with more appliances, using 800 units or above, end up cornering a large chunk of the subsidy.

The study suggests that if the state government redesigns its subsidy distribution criteria--we further explain how--it can free up Rs 306 crore ($42 million). Such an exercise across the country could help save a substantial portion of the Rs 110,391 crore ($15 billion) that all states collectively distributed as subsidies for electricity consumption in 2018-19. This is six times higher than the 2020 budget estimate for the Union ministry of power.

“People across India have been hit hard by the economic shock of COVID-19. It is more pressing than ever to ask: are the right people receiving government support?” says Christopher Beaton, the project lead at IISD. “And could we do a better job at focusing support on the people who really need help the most?”

Better targeting of subsidies and the savings accrued through such moves would also help debt-laden electricity distribution companies (discoms) stuck with low-tariffs, the study says, adding that state subsidy payments do not fully compensate for the gap between the actual cost of supply and revenue realised. This has only worsened with the COVID-19 crisis. "Covering the cost of supply is essential to expanding and improving the quality of electricity,” it says.

One of the biggest hindrances for power subsidy reforms, as we discuss below, is the lack of political will. Increasing the tariff for residential users to meet the actual supply cost or removing subsidy benefits, political parties fear, could cost them their voter base.

How subsidy is distributed

The Jharkhand government distributed Rs 1,250 crore as electricity consumption subsidies in 2018-19 and of this, Rs 984 crore ($140 million), or 79%, is meant for residential consumers--the biggest beneficiaries of the scheme.

As per the 2019-20 numbers, residential consumers make up 91% of the 4.5 million consumers of Jharkhand Bijli Vitran Nigam Limited (JBVNL), the state-owned discom. These consumers also account for 61% of its total anticipated sales volumes. Agriculture consumers make up 1.3% of its consumers and account for only 2% of its sales, the study says.

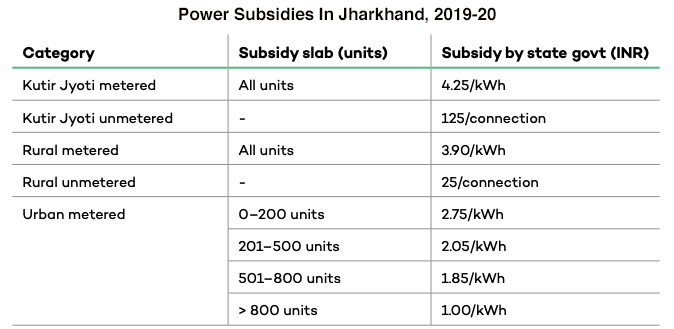

Within the residential consumer segment, the Jharkhand government provides subsidy for electricity consumption for users across capacities, as the table below explains.

According to the current subsidy design in Jharkhand, among rural consumers--including those in the Kutir Jyoti scheme for electrification of households below the poverty line--flat subsidies are provided to consumers, irrespective of their monthly consumption.

For urban residential consumers, though, there are slabs: Consumers who use up to 200 units of electricity get a subsidy of Rs 2.75 per unit and the subsidy falls to Rs 1.00 per unit as the monthly average consumption rises above 800 units per month.

Source: Jharkhand State Energy Department data, 2019, cited in the study by International Institute for Sustainable Development and Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy

Note: The figures are for Jharkhand Bijli Vitran Nigam Limited consumers.

The current subsidy distribution design enables rich households to get more subsidy by consuming more power, the study finds from analysing electricity bills. It also distributes these households into five wealth-quintiles (quintile one being the poorest and five the richest) based on a “wealth index” created through reported income, reported expenditure, and asset ownership. (A quintile represents 20% of the surveyed households.)

The “wealth index” approach is more accurate--because it includes more than one indicator described above to ascertain wealth--than the common ‘ration-card method’ wherein the possession of a card decides whether a household belongs to ‘poor’ or ‘not-poor’ categories, Sharma, co-author of the study, told IndiaSpend. It is also an improvement on the ‘expenditure method’ often used by the government wherein quintiles are established on the basis of self-reported household expenditure on different products.

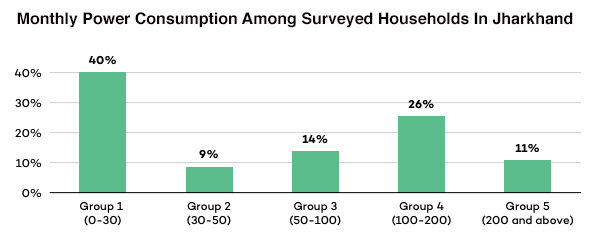

The analysis finds that 63% of surveyed households use fewer than 100 units of electricity per month, as we said earlier. Only 26% of households use 100-200 units of electricity per month and a mere 11% of households use more than 200 units.

Source: Survey of 900 households in Jharkhand, cited in the study by International Institute for Sustainable Development and Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy

Who benefits most

In rural areas, rich households categorised under quintiles four and five--that is, the richest 40%--use 60.6% of the total electricity subsidy provided by the state government, the study finds. The poorest 40% households--under quintiles one and two--only use 25% of the subsidy. In urban households too, the two richest quintiles use 60.2% of the subsidy and the poorest two 25.4%.

In rupees, the richest 20% households in rural areas use an average of Rs 374 per month, more than three times the Rs 106 used by the poorest households. In urban spaces, the amount decreases a bit but the gap between rich and poor households remains the same, according to the study. (See the table below)

“According to this model [current subsidy design], those consuming more than 800 kWh per month can receive up to four times more government support than those who use below 50 kWh,” Sharma said.

The study finds that the results do not change much even if other approaches are used to categorise households into wealth quintiles. For example, even using the ‘expenditure method’ showed that the two richest quintiles use close to 65% of the subsidies in both rural and urban regions. The poorest two quintiles still use between 18-25% of the subsidies as per this method.

Targeting subsidies better

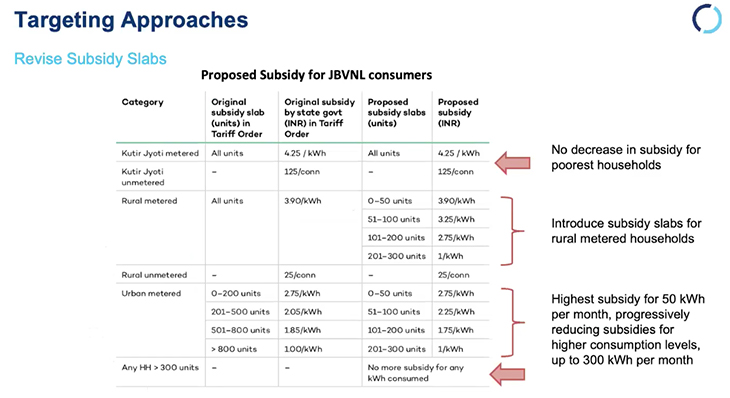

Subsidies can be designed to facilitate better distribution, the study says. The design it recommends includes introducing slabs for rural metered connections, instead of the current flat subsidy of Rs 3.90 per unit per month. Plus, it emphasises restructuring the slabs for both rural and urban metered consumers while keeping the per unit subsidy for urban areas slightly lower than rural areas. (Please see the table below)

In the new recommended design it is suggested that the subsidy for poorest households and unmetered connections be left untouched. It also suggests that the first cut-off for the subsidies--which currently is 0-100 units--should be changed to 0-50 units since most poor households consume fewer than 50 units per month.

The group that consumes 0-50 units per month should get the most subsidy of Rs 3.90 per unit in rural areas and Rs 2.75 in urban areas. The maximum consumption group for which subsidies should be offered needs to be limited to 201-300 units per month. This group will receive Rs 1 per unit of subsidy in both urban and rural regions.

The government should remove any subsidy to users who consume more than 300 units every month, as per the study.

Source: Survey of 900 households in Jharkhand, cited in the study by International Institute for Sustainable Development and Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy

How restructuring will help

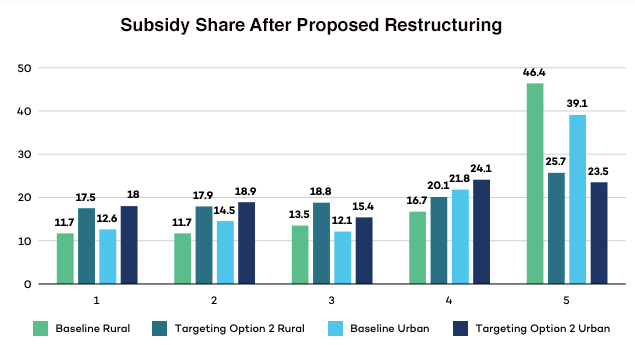

If the current subsidy structure is redesigned, the poorest rural households in the first two quintiles will start receiving 35% of the total subsidy offered by the government--this is 12 percentage points more than what they receive currently, the study estimates. The richest rural households in the last two quintiles, on the other hand, will receive 46% of the total government subsidy, 17 percentage points less than what they receive today.

For urban areas, subsidies for the poorest two quintiles will increase 10 percentage points, from 27% to 37%. For urban rich households, it will decrease from 61% to 48%.

This change will free up Rs 306 crore ($42 million) of government subsidy, 31% of the total subsidy expenditure on residential consumers by the Jharkhand government in 2018-19.

“We notice that the change in subsidy incidences [after the restructuring]--even though improves slightly--largely remains regressive,” Sharma of IISD. “It is very challenging to find a programme that delivers 100% of the benefits to only the targeted individuals.”

Sharma also pointed out that electricity supply is an election issue in India and restructuring its subsidies might be difficult for state governments without understanding “which consumer group has the most influence”.

Promises of free or cheap electricity can influence election results so political parties tend to leave power reforms to the next government, according to a June 2017 study by the Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi-based think-tank, that investigated the links between politics and power reforms in Uttar Pradesh.

Source: Survey of 900 households in Jharkhand, cited in the study by International Institute for Sustainable Development and Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy

Looking ahead

The report provides specific recommendations for governments based on the Jharkhand study.

In the short term, the researchers recommend a highly cautious approach, given the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on citizens: removing the subsidy only for households consuming more than 300 units of electricity per month.

Once the economy begins to recover, the report says, governments should progressively reduce subsidies for groups that consume between 50 units and 200 units per month.

Savings accrued through the restructuring and better targeting of subsidies could be redirected to improve electricity supply, support poor households consuming less than 50 units per month, or assist with recovery from COVID-19, the report says.

For other states the study recommends finding context-specific solutions with similar analysis of who benefits most from electricity subsidies and by testing different targeting strategies. Experts say this would allow states to improve targeting of subsidies without compromising energy access and affordability.

State governments should also work together with state agencies that maintain registries of the poor, to make sure energy access policies align with accurate data on household wealth, the study suggests.

(Tripathi is an IndiaSpend reporting fellow.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.