Without States On Board, DISCOM Reforms Could Fail

New Delhi: Power sector reforms announced as part of India’s COVID-19 economic package could fall short in achieving the goal of a financially healthy electricity distribution sector, unless state governments support these reforms and distribution companies (DISCOMs) deal with legacy issues, such as inaccurate billing and inefficient payment collection, experts have told IndiaSpend.

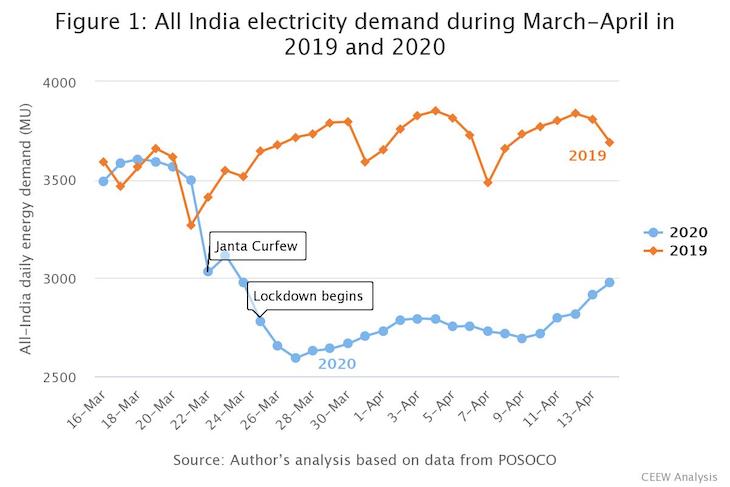

COVID-19 has reduced power companies’ revenues as electricity demand has gone down by nearly 20%. This is because industries and commercial establishments, major buyers of electricity, have been shut due to the lockdown. DISCOM losses could soar to Rs 50,000 crore in the financial year 2020-21, a 67% increase from last year’s estimated losses of Rs 30,000 crore.

To improve the health of the power sector and promote private investment in DISCOMs, Union finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a roadmap to change the sector’s investment policy and power tariffs. These include: privatisation of DISCOMs in union territories (UTs); progressive reduction in cross subsidies under which, currently, DISCOMs charge industrial and commercial consumers a higher tariff to subsidise electricity for households; and direct benefits transfer (DBT) of electricity subsidy rather than paying the subsidy directly to DISCOMs.

Most of these reforms are not new, and have been announced in the past, but were never enforced.

“As before, enforcement will be the key. Else we are going to be discussing the same points again in the future,” said Deepak Krishnan, associate director of the energy programme at the World Resources Institute India (WRI India). In the current announcements, what is missing is a vision or strategy on how DISCOMs will be made to shape up to deliver in a changed regime and also share the wins, he said.

Lack of a clear implementation strategy

The finance minister announced the following reforms on May 16, 2020:

- Power departments and DISCOMs in UTs will be privatised to improve services to consumers and for operational and financial efficiency. “This will also provide a model for emulation by other utilities across the country,” she said.

- The government will set standards for the quality of electricity supply and decide on penalties for load shedding to protect consumers.

- Cross subsidies will be reduced progressively.

- Those who require an electricity subsidy will receive it through a DBT. Currently, state governments pay subsidies directly to DISCOMs in return for low tariffs, free power supply to farmers and for unmetered connections.

- The use of smart meters will be promoted.

- Getting rid of regulatory assets. Regulatory assets arise from the practice of allowing distribution companies to push the recovery of current costs of power consumption to the future through future tariff hikes. Because these hikes are sporadic and mostly not enough to cover the costs of power generation and supply, regulatory assets have crossed Rs 1 trillion, according to a report in Livemint.

Most of the tariff reforms suggested by the government were already laid out in the May 2018 draft of the proposed amendments to the National Tariff Policy 2016. The move to privatise electricity distribution was also alluded to in the Draft Electricity (Amendment) Bill 2020, released on April 17, 2020.

Experts said that without a concrete strategy to implement these reforms in coordination with states, these too would fail like the government’s first bailout and reform programme for DISCOMs, the Ujwal DISCOM Assurance Yojana (UDAY).

UDAY had attempted some of these reforms but it was not successful, IndiaSpend reported in June 2019. The programme aimed at clearing debt from DISCOMs’ balance-sheet, reducing their Aggregate Technical & Commercial (AT&C) losses, the gap between the cost of power supply and the revenue collected from consumers, and increasing power tariffs to reflect the actual cost of power. The scheme concluded in March 2020 but DISCOMs were still in loss and many had not undertaken reforms to improve their financial situation.

State DISCOMs might not privatise

Indian UTs come directly under the Union government so the path to privatisation would be easy. However, it does not necessarily mean that state-owned DISCOMs across India would suddenly start adopting the model. The model of a private distribution company, such as Tata Power and Reliance Infrastructure-owned BSES in Delhi, has existed for years but state DISCOMs have not adopted it.

AT&C losses for private DISCOMs in Delhi were around 10%, compared to 20% for state-owned DISCOMs, as of December 2019, according to government data. AT&C losses are the sum of a DISCOM’s losses due to technical reasons, theft, default in payments, billing and collection--an indication of a DISCOM’s efficiency and health.

“The move to privatise UT DISCOMs may not be an example that states choose to emulate,” even as the benefits are clear, said Krishnan of WRI.

While privatisation can be one of the options, it would also be good to see how measures can be introduced to enable DISCOMs to perform better, said Krishnan.

Financial disincentives if DISCOMs do not implement reforms

Earlier, on May 13, 2020, the Union government had announced a Rs 90,000-crore economic package for the power sector which included non-banking lenders Power Finance Corporation and Rural Electrification Corporation offering conditional loans of Rs 90,000 crore to DISCOMs to pay their dues to power generation companies (GENCOS) and transmission companies (TRANSCOS).

DISCOMs owed Rs 97,653 crore to GENCOS as on March, 2020, according to the latest data available on the power ministry’s portal. Of this, Rs 85,784 (89%) is overdue--payment defaults over 60 days.

These loans will be given only if the state government agrees to guarantee the loans, Sitharaman announced on May 13, 2020. The Rs 90,000-crore loan that the government will give DISCOMs can be recalled if utilities do not put efforts towards “loss reduction”, Union power minister R.K. Singh said in an interview on May 14, 2020.

Adding a further condition, the finance minister on May 17, 2020, announced that the limit of borrowings for the state governments--to acquire additional financial resources amid a revenue crunch due to COVID-19--would be increased from 3% to 5% of the gross state domestic product. Part of the additional borrowing would depend on reforms in four sectors including power distribution.

These conditions for state-owned DISCOMs to receive help from the Union government are in line with the lessons for the government from the failure of UDAY: the need to introduce disincentives for not meeting targets, the Union power minister said in his interview to The Financial Express on March 9, 2020.

“Every time the Centre gives money to DISCOMs to strengthen their systems and infrastructure, they add new equipment, but end up not maintaining the facilities, because they are making losses and are financially broke,” he said. “[T]he disincentive for not meeting loss trajectories would be curtailment of the funding sources.”

Unless the legacy issues of DISCOMs--low electricity tariffs, cross subsidies, inefficient consumer billing and payment collection, delays in electricity dues by government departments and subsidy payments by states--are not methodically addressed, the disincentives would not be effective in bringing discipline and efficiency in the operation of DISCOMs, Vibhuti Garg, energy economist at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), told IndiaSpend.

Here are some of the legacy issues that have been pulling DISCOMs down and how electricity reforms could help resolve these issues:

State government payments: A DISCOM’s problems are accentuated by states not paying subsidies and power bills on time, said Garg of IEEFA. Currently, state governments are supposed to give these subsidies to DISCOMs at the end of each financial year in lieu of free power supply to farmers and for unmetered connections. Many states are late in paying these subsidies to utilities and owe about Rs 57,000 crore in subsidy payments.

The DBT would ensure that delayed payments from the government do not impact DISCOMs’ revenue realisation, said Garg.

Several government departments across the country owe cumulative dues up to Rs 54,000 crore to DISCOMs, the power minister had said in the interview on May 14, 2020. Therefore, the recovery package for the power sector should not be limited to making sure DISCOMs pay the GENCOS. Instead, it should also ensure that DISCOMS are paid on time, by all departments concerned, including the government, said Krishnan of WRI.

Recovering the actual cost of power: Higher tariffs that reflect the full cost of electricity supply are necessary to protect DISCOMs in dealing with sudden revenue shocks. This can be done by increasing tariffs regularly and getting rid of regulatory assets.

For instance, without commercial and industrial activities during the nationwide lockdown, India’s daily power demand dropped to 2,592 million units (MU), down by 28% on a year-on-year basis, according to the Delhi-based think-tank, Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). This resulted in a revenue loss of nearly Rs 15,000 crore over three weeks from March 25 to April 14, 2020, the analysis said. The last time India’s power demand was at these levels during the same period was in 2014.

The CEEW has done a three-part analysis (here, here and here) on the COVID-19 induced power sector crisis.

In the past too, the Union government has tried to get rid of regulatory assets by pushing states to increase electricity tariffs regularly under the UDAY programme. States were to increase power bills by 6% a year for four years until March 2019, but the average increase over the period was half of that, IndiaSpend reported in June 2019.

To answer how this time would be different from previous attempts of reforms, Krishnan of WRI said that more transparency is required to explain how these measures are going to be implemented.

Cross subsidies: In most Indian states, household and agricultural consumers do not pay a tariff that covers the average cost of electricity supply; the difference is cross-subsidised by charging a higher tariff to commercial and industrial consumers. Political parties also use the promise of free power or reduced power tariffs as a political tool in elections, as IndiaSpend reported in April 2018.

Reduction in cross subsidies will make the industries competitive as power costs are a big element of their overall cost, Garg of IEEFA told IndiaSpend. Reduced power costs will also help in promoting the establishment of domestic manufacturing bases, she added.

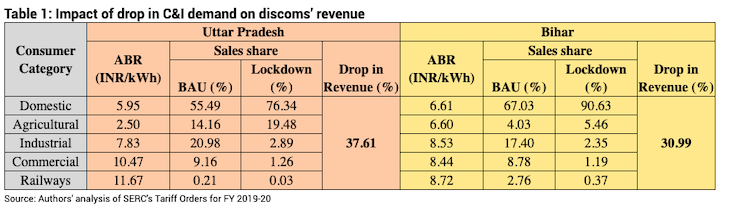

For instance, in Uttar Pradesh (UP), the power cost for domestic users is Rs 5.95 per unit, for industries it is Rs 7.83 per unit and for the commercial sector it is Rs 10.47 per unit. Together, on regular days, the commercial and industrial sector, along with railways accounts for just over 30% of the total power sales of a DISCOM. This reduced by about 26 percentage points during the lockdown, but resulted in a 38% drop in DISCOM revenue, as these sectors pay a higher tariff, as per the CEEW analysis, based on power consumption data from the preceding financial year.

Source: Analysis by Council on Energy, Environment and Water

Issues in billing consumers and collecting payments: DISCOMs’ revenue is further impacted by the fact that most are unable to bill consumers correctly and collect payments on time. Though automated meter-reading infrastructure and smart meters are now being used, these cover only a small fraction of domestic consumers, according to the CEEW analysis.

The problems in billing and payment collection were exacerbated during the lockdown as the government temporarily terminated activities of meter-reading and physical delivery of bills across the country. Most DISCOMs billed consumers on average consumption of the previous months but these bills would be considerably understated because the increased consumption due to summer would not be accounted for, said the CEEW analysis.

To overcome this issue of seasonal variation, the Indian state of Telangana has decided to bill consumers on the consumption records from the same month in the previous year, said the CEEW analysis, suggesting that DISCOMs in other states could turn to such options.

Currently, electronic payments are the easiest option to pay an electricity bill. However, only a few consumers across the country pay their electricity bills online. For instance, only 19% of all urban consumers in UP paid their bills online in December 2019, the analysis said.

DISCOMs need to encourage online payments through appropriate incentives such as discounts or bill waivers for customers who are paying the bill online, said the CEEW analysis. For consumers who are not comfortable with online payments, DISCOMs can offer alternative options, such as bill payments at nearby kiosks, common service centres and grocery stores.

(Tripathi is an IndiaSpend reporting fellow.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.