How Agriculture Consumes 23% Of India’s Electricity & Picks 7% Of Tab

The latest episode in the Delhi ‘power’ tussle was something of a surprise. The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP)-led Government (which subsequently resigned) announced an amnesty of sorts for consumers who didn’t pay their bills during a particular period. So, is there a rationale for the step? Simply put, if others don’t have to pay fair prices for power, why should consumers in Delhi (and elsewhere) do it?

A quick glance at the power 'equation’ in the agriculture sector is actually quite revealing as to how the economics of India’s electricity business is so out of whack. While there might be good reason for subsidies and the like, it is clear that the combined weight of subsidy and inefficiency has caused near permanent damage to all parties concerned, including the consumer. And the bigger problem might be in correcting the perception of cheap or free goods rather than just increasing the tariffs.

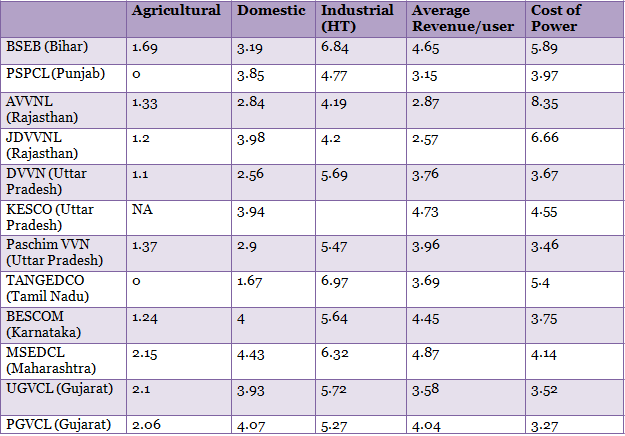

Numbers from Power Finance Corporation (PFC) indicate that agricultural users across the country pay only one-fourth the price for the power they consume compared to other users. This would have been bearable had the power distribution companies been profitable but sadly that isn’t the case.

The aggregate losses of power distribution companies across India added up to Rs 92,845 crore (pre-subsidy) during 2011-12. During FY12, the combined net worth of all these utilities also turned negative. The biggest culprits here are the distribution utilities of Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan.

Delhi seemed to be the only state with profits (pre-subsidy) amounting to Rs 1,710 crore. Gujarat had a profit of Rs 623 crore with subsidy and a loss of Rs 477 crore without the subsidy. Karnataka too had a profit of Rs 176 crore with the subsidy and a loss of Rs 1,176 crore without it.

So, how much do agricultural users pay compared to the rest of us? Agriculture consumed 23% of the electricity sold in India during 2011-12 but its revenue share was just 7%. To get a more accurate picture, we need to look at the price paid per unit.

For instance, the two distribution utilities of Haryana (DHBVNL and UHBVNL) charged an aggregate price of Rs 3.77/unit and Rs 3.01/unit to their consumers during FY12. And the price that was charged to agricultural users? An incredible 31 paise/unit and 34 paise/unit.

In case of neighbouring Punjab, the situation is even better – the rate charged to agricultural consumers is 0.00 – free power. Cost of power was zero for farmers in Tamil Nadu as well. Bihar State Electricity Board (BSEB) charges Rs 1.69/unit to farmers against an overall price of Rs 4.64 for all consumers.

Agricultural users aren’t the only ones being subsidised. Many states also subsidise household consumers. The average price charged to consumers by BSEB was Rs 3.19/unit for FY12 while the cost of power to BSEB was Rs 5.89/unit.

Table 1: Who Pays What For Power

All Figures in Rs/Unit

Source: PFC

The logic given for subsidising agricultural inputs like power and fertiliser is that it helps keep food prices low. But is that really true? We think not as, on the other side of the equation, the Government also sets the minimum support price (MSP) for key cereals wheat and rice.

This ensures that farmers get a minimum price for their produce and sets a floor price below which food prices can’t fall. Both of these are laudable goals but taken together, they don’t quite add up. After all, MSP defeats the very purpose for which the Government is subsidising electricity and fertilisers.

Meanwhile, high food prices hurt the poor because of which another leg has been added to the subsidy table – the Food Security Bill. Perhaps, AAP does have a point. If villages don’t pay for the power they use, why should the rest of us? This seems to be the easier option. A more difficult option will be to rationalise power prices, and give targeted subsidies to poor farmers/poor urban residents.

By and large, almost all utilities charge customers less than the cost of power. The difference is either made up by subsidy or carried as loss on the balance sheets of these companies. Being private sector players, the Delhi utilities charge market rates for power. Perhaps that is what makes people think they are ‘over-paying’ for power.