India Must Act Swiftly To Stop This ‘Silent Pandemic’ From Becoming Catastrophic

By 2050, #AntimicrobialResistance is expected to claim 10 million lives a year globally, more than cancer and diabetes combined, with most of this burden falling on low- and middle-income countries

Mount Abu, Rajasthan: In early December 2022, Anamika (name changed), a university professor in Pune, contracted a fever, and simultaneously experienced abdominal pain, and a burning sensation and pain while passing bloody urine. Over 50 days and four antibiotics later, the infection persisted. It was only in February, after a doctor prescribed a potent antibiotic--reserved to treat infections from multidrug-resistant infections--that some of her symptoms were resolved.

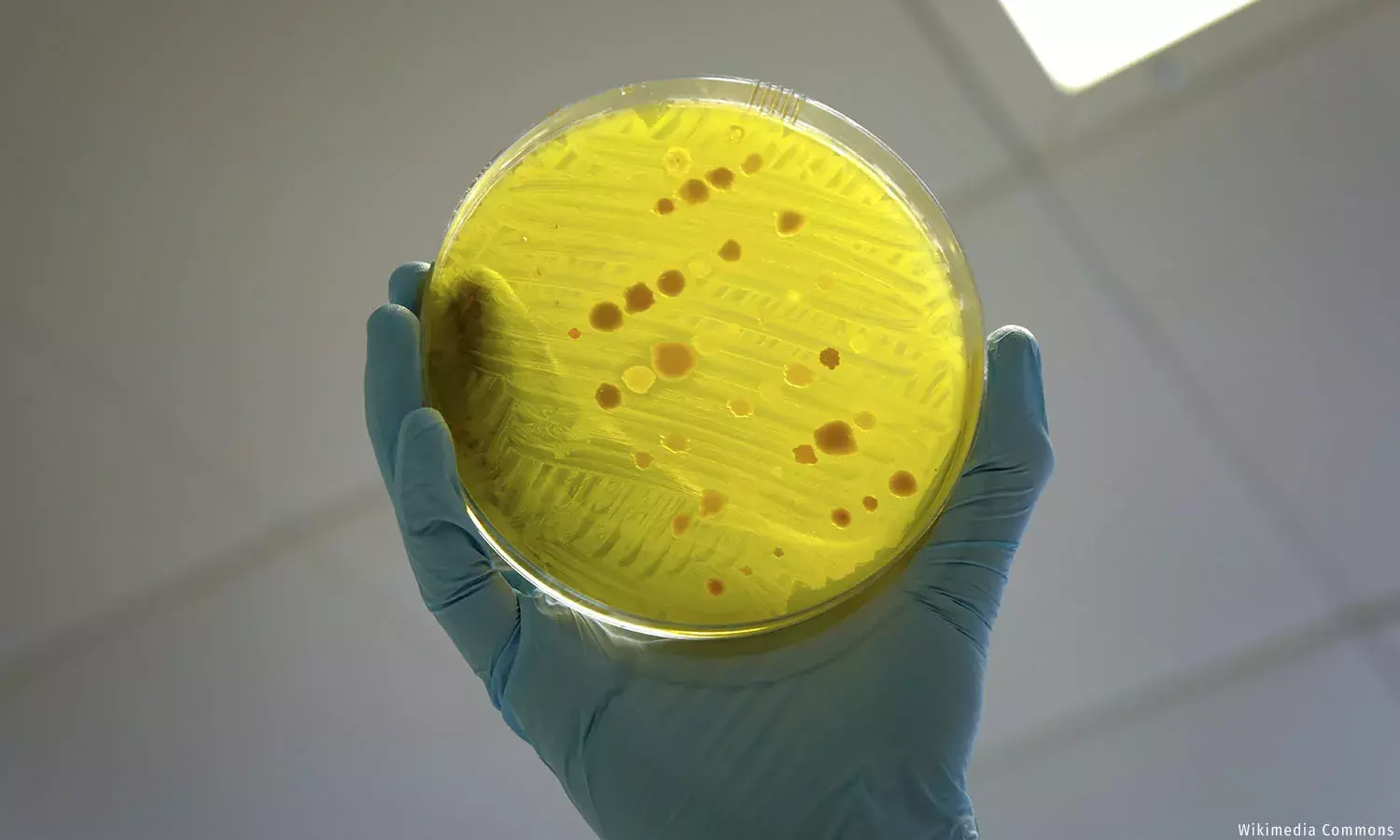

In India, bacteria that pose the greatest threat to human health--which the World Health Organization (WHO) calls critical-priority class pathogens (as against high- and medium-priority class pathogens)--demonstrate more than 50% resistance to over half of the available antimicrobials, according to a recent study by the Max Institute of Healthcare Management at the Indian School of Business, funded by the Center for Global Development.

Drug resistance accounts for 4.1% of all the years of life lost due to premature mortality in India, as against 2.2% globally, the study estimated. Essentially, drug resistance snatches away 40% more life years in India than it does worldwide.

By 2050, antimicrobial resistance is expected to claim 10 million lives annually across the world, more than cancer (8.2 million) and diabetes (1.5 million) combined, with most of this burden falling on low- and middle-income countries.

Infectious diseases have declined as a cause of mortality in India but are still a cause for concern. In 2019, bacterial infections were implicated in 1.79 million deaths across the country by the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance. That’s 19% of the 9.92 million deaths estimated to have occurred in that year. Of those who died due to a bacterial infection, 16.6% succumbed because the bacteria was resistant to the available arsenal of drugs. Further, 58.1% had a bug that was implicated in their death, but antimicrobial resistance may or may not have been a factor.

Patients succumb to infections either because the disease-causing pathogen was immune (read ‘resistant’) to the drug--just like all the drugs Anamika took before a doctor in Mumbai prescribed faropenem--or because they could not access the more potent antibiotics they needed.

‘Doctors kept prescribing low-end antibiotics’

In December 2022, when the symptoms first appeared, Anamika promptly saw a doctor, who diagnosed her condition as a urinary infection, and prescribed a five-day course of antibiotics.

Anamika’s fever abated but her urinary symptoms persisted. By then, a urine culture report had come in, which showed that she had a multi-drug-resistant strain of E. coli, the bacteria that is responsible for most of the urine infections globally. So, Anamika took a second and a third opinion, and both doctors prescribed the same drug to be had for a fortnight.

A second urine culture in late December showed that her infection, and hence, her urinary symptoms were persisting. So, Anamika consulted a urologist, who put her on a three-day intravenous course of a different antibiotic, followed by 15 days of an oral antibiotic. When a third culture showed status quo, the urologist changed the drug for another 15-day course. A fourth culture showed still no change.

The last doctor Anamika consulted, in Mumbai, in February this year, prescribed faropenem, to be followed by one of the milder antibiotics she had had earlier, “to be on the safe side”.

The WHO’s essential medicine list classifies antimicrobials as ‘Access’, ‘Watch’ or ‘Reserve’ drugs. Faropenem is a very potent antibiotic that falls under the WHO’s ‘Reserve’ list--that is, antimicrobials that should be considered ‘last resort’ options for the treatment of confirmed or suspected infections due to multidrug-resistant organisms.

Faropenem resolved Anamika’s acute urinary symptoms but didn’t cure her completely. It took another four months to treat her urinary retention. And, until today, she continues to suffer from debilitating nerve pain in the perineum and pudendal neuralgia--that is, pain in a nerve in the pelvic region--because of which she cannot sit for extended durations, and for which, she undergoes physiotherapy twice a day.

“I cannot understand why the doctors I approached kept prescribing low-end antibiotics,” Anamika told IndiaSpend. “They should have realised that my case was ‘that’ serious in the beginning.”

Why is antimicrobial resistance growing in India?

Bacteria develop resistance when they are overexposed to an antibiotic, explained microbiologist Gagandeep Kang, a professor in the Department of Gastrointestinal Sciences at Christian Medical College, Vellore, and Fellow of the Royal Society. “If a bacterium sees an antibiotic frequently, then the chances of it developing resistance by any mechanism is higher.”

The antimicrobial resistance database of the Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance and Research Network, an initiative of the Indian Council of Medical Research, shows that certain pathogens have developed greater resistance to some drugs between 2016 and 2021 (see table below).

“All of these bacteria are Gram-negative bacteria, which generally develop resistance faster than Gram-positive bacteria,” commented Kang on this development. Bacteria may be either Gram-positive or Gram-negative, depending on how the bacteria reacts to a Gram stain test. Gram-negative bacteria are more harmful. Most of the antibiotic-resistant priority pathogens identified by the WHO are Gram-negative bacteria.

“Bacteria can acquire resistance by picking up genes on genetic material that can move around from one species to another, or by mutations in their DNA,” Kang added. “Since Gram-negative species live in the gut with other species, they are well placed to easily and quickly exchange their genetic makeup to become resistant to certain antibiotics.”

Overexposure to antibiotics is a huge problem in India not only because of the sheer quantity of drugs consumed but also because of the kinds of drugs that are being consumed.

Globally, the aim is for antibiotics on the WHO’s ‘Access’ list to account for 60% of the use of drugs, to preserve the more potent drugs for those who really need them. In India, however, ‘Access’-classified antibiotics accounted for only 27% of the drugs sold in the private sector in 2019, according to a 2022 Lancet study. ‘Watch’ category antibiotics accounted for 55% of the drugs sold.

Government hospitals also rely more on ‘Watch’ and ‘Reserve’ category drugs. A 2019 multicentre study of the antibiotic use in hospitalised patients in tertiary care centres in India showed that 38% of the prescriptions are from the ‘Access’ category of antimicrobials.

‘Watch’ category drugs tend to be broad-spectrum antibiotics--that is, antibiotics that act on a large number of bacteria and hence, drive resistance more than drugs that act on a single bacterium.

Pointing out that broad-spectrum antibiotics “should ideally be used sparingly”, the Lancet study authors labelled their current usage in India “a public health concern” and called for the institution of new regulations and strengthening of existing ones “to monitor and regulate the sale and use of antibiotics while improving access to appropriate antibiotics through the public health system”.

But, restricting the access of ‘Watch’ and ‘Reserve’ category drugs to patients on the rolls of government programmes and to hospitalised patients is not a priority in India.

India lacks a national programme for antimicrobial resistance akin to the national programme for tuberculosis (TB), said Kamini Walia, a scientist in the Division of Epidemiology and Communicable Diseases, Indian Council of Medical Research. Calling this gap “a huge downside”, she further explained: “Two new drugs introduced for TB have not been made available in the open market but are only available through the programme. If we had a framework to regulate antimicrobial use on the same lines, it would be easier to bring drugs to treat highly-resistant pathogens to India.”

India’s existing National Programme on AMR (antimicrobial resistance) Containment aims to establish a laboratory-based surveillance system and surveillance of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial usage. It also aims at strengthening infection control practices and at promoting the rational use of antimicrobials through stewardship practices and greater awareness.

Reviewing the National List of Essential Medicines in 2022, the Standing National Committee on Medicines reported: “Making antimicrobial agents unavailable in the market, perhaps, is not an appropriate strategy.”

Instead, the committee favoured “continuous sensitisation of prescribers, strict prescription audit and antimicrobial stewardship programmes” to discourage irrational antimicrobial prescribing and prevent antimicrobial resistance.

So far, those measures aren’t working.

Filling the gaps in the availability of high-end antibiotics

On the one hand, India is seeing the irrational use of antibiotics causing drug resistance, and on the other, the limited availability of some of the most potent antibiotics.

The National List of Essential Medicines revised and recompiled in 2022 included 16 of 19 antibiotics in the WHOs 2019 essential medicines list’s ‘Access’ category, 11 of 12 ‘Watch’ category antibiotics and only one of seven antibiotics in the ‘Reserve’ category.

Despite increasing resistance levels, the Standing National Committee on Medicine’s decision to include only one ‘Reserve’ category antibiotic was a prudent move, explained committee member Lalit Kumar Gupta, a professor in the Department of Pharmacology, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi.

“‘Access’ and ‘Watch’ category drugs are still effective against most of the microbes we see in India,” Gupta said. “We thought we should only include as much as is needed immediately, and hence included almost all the ‘Access’ and ‘Watch’ category drugs, and keep the ‘Reserve’ category drugs for future. We are open to modifying the list on a dynamic basis.”

But when it comes to procuring essential medicines at the level of states, the respective medical services and/or medical supply corporations enter into rate contracts only for the essential drugs list framed by the respective state’s health department. In two of the three states we spoke to (Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat), this procurement is limited to low-end antibiotics with the medical colleges having to source the high-end antibiotics themselves.

“The 287 essential drugs we procure mostly include those prescribed in general hospitals, primary and secondary health centres,” explained Sajit Udayabhanu, a drug procurement consultant with the UP Medical Services Corporation. “We procure generic drugs from the open market via e-tender system to get the best competitive price, which in any case wouldn’t apply to new / latest high-end antibiotics that may be under the monopoly of the patent holder. New high-end antibiotics as are mostly used in medical colleges are included in specialty drug lists, currently not procured by us.”

Gupta points out that this bifurcation of responsibility is desirable. “We don’t want high-end antibiotics to be bought in bulk through e-tendering systems because then they are sure to be over-prescribed,” he said. “In fact, even in government hospitals, where prescriptions are written by interns, junior residents, senior residents as well as consultants, prescriptions for high-end antibiotics must be countersigned by the consultant. Also, high-end antibiotics are usually only prescribed to patients admitted to intensive care units, and hence, lesser quantities of these are needed.”

Here, the ISB study authors point out that limiting access to ‘Reserve’ category drugs by not including them in the essential drugs list increases the out-of-pocket expenses of patients who aren’t hospitalised. Instead, states should make these drugs available and affordable, while keeping the usage under surveillance and strengthening stewardship guidelines. In fact, to ensure that access in smaller hospitals is made contingent on robust stewardship practices, Deepak Jena, assistant professor, Strategy, Indian School of Business, and one of the study authors, recommends “a rating and accreditation system on stewardship practices for smaller hospitals”.

An accreditation assessment would check the evidence for prescriptions (microbiology reports) and systems the hospital has instituted to hold doctors accountable for their prescriptions, among other things.

Further, to lower the prices of the drugs that would otherwise be very expensive especially when bought in small volumes by individual institutions, the ISB study proposed pooling demand by creating a more comprehensive essential medicines list.

In fact, in Gujarat, even ‘Watch’ and ‘Reserve’ category antibiotics are procured by the Gujarat Medical Services Corporation Limited, and since the quantities procured are huge, the corporation gets the best prices.

“Centrally pooling demand would be helpful,” agreed Walia of the ICMR. “A central agency could take up India’s cause on the basis of the huge volume of consumption.”

Further, pointing out that several patented antibiotics are still not being made in India, Walia said that a central agency could also allay apprehensions of manufacturers who are hesitant about entering India because they foresee their product as becoming redundant very soon in our huge-but-largely-unregulated antibiotics market.

“Centralised procurement of new / latest antibiotics by pooling the demand of various consuming centres would help get the best competitive price,” agreed Udayabhanu.

In Kerala, Karunya Community Pharmacy, a state-owned pharmacy chain established by the Kerala Medical Services Corporation, centralises demand, buys at very favourable rates and passes on this gain to patients with prescriptions as well as public hospitals. For instance, Karunya procures meropenem, an antimicrobial from the ‘Watch’ category, at half of the maximum retail price (MRP), and colistin, an antimicrobial from the ‘Reserve’ category, at one-third of the MRP, according to the ISB report.

“Another way to improve access to high-end antibiotics could be to source from private aggregators and sellers, like online vendors,” proposed Parshuram Hotkar, assistant professor, Operations Management, Indian School of Business, one of the ISB study authors. “Online vendors could also aggregate demand for smaller private hospitals if and when the state lacks the infrastructure to pool demand centrally at the inter- or intrastate level.”

To continue the previous example, meropenem 1 gm injections can be availed from MrMed.in at 83% off the list price.

“Most bulk procurements can be fulfilled at 20-60% less than the MRP,” said Saurab Jain, co-founder, MrMed.in. “Even if demand isn’t pooled, we fulfil every order at a substantially discounted rate.”

Oral faropenem, the drug that cured Anamika, was available on MrMed.in at a discount between 17% and 37%, depending on the brand. While it is reassuring to know that high-end antibiotics may be availed at substantially reduced prices, the focus must not shift from their overuse.

Anamika’s ordeal is not a one-off case; this reporter has seen three cases of lingering stubborn E. coli in her own family in the last couple of months. You may have too. To put this in context, now that everyone understands the gravity of a pandemic, here’s what the NLEM 2022 report says: “Antimicrobial resistance is becoming a silent pandemic which if not addressed effectively today, will be catastrophic tomorrow.”

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.