Without Knowing Its Test-Tube Babies, India Seeks To Control Their Lives

Surrogate mothers rest inside a temporary home provided by an in-vitro fertilisation centre in Anand, Gujarat. The government has hardly any data to help it regulate the assisted reproductive technology industry, and instead of legislating to regulate the entire industry, it has chosen to focus on only one part of it--surrogacy.

It has been nearly four decades since the birth of India’s first test-tube baby. In this time, assisted reproductive technology (ART) has grown into an industry worth hundreds of crores. But instead of legislating to regulate the entire industry, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government has chosen to focus on only one part of it--surrogacy.

On August 24, 2016, the union cabinet put its stamp on the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill without a clear idea of the exact size or shape of the entire ART industry in India. The future of an older and more comprehensive bill, the Assisted Reproduction Technology (Regulation) Bill, framed in 2010, is now uncertain, its provisions reduced to guidelines.

The government has hardly any data to help it regulate the ART industry: How many babies in the country are born every year through these techniques? How many in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) clinics are there? How many cycles are they conducting on how many women? Which of these clinics offer surrogacies, what do they charge and how much are surrogates paid?

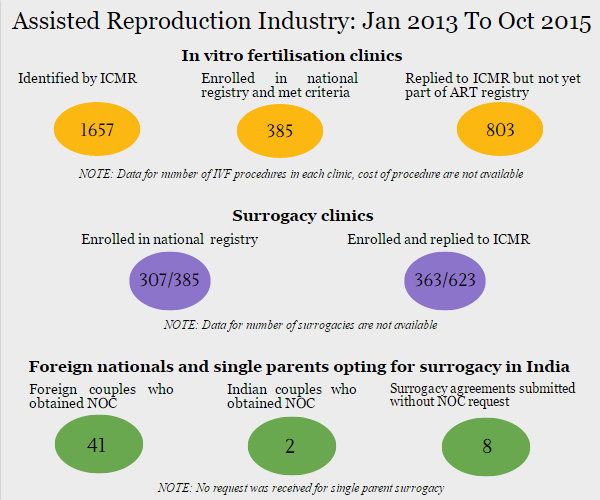

The only existing data on the ART industry were collected by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) between January 2013 and October 2015 in an unfinished attempt to set up a national registry. The council identified 1,657 clinics for assisted reproduction; of these 623 confirmed themselves as ART clinics, 180 as sperm and egg banks. The remaining did not respond.

Only 385 clinics actually fulfilled ICMR’s criteria on infrastructure--trained manpower and procedures undertaken as per a prescribed proforma--and made it to the national registry. Of them, 307 conduct surrogacies. This is the only information currently available on the ART industry.

The registry was put on hold in October last year, with critical questions still unanswered. The lack of data means the government has no information with which to regulate the booming ART sector.

Source: Indian Council of Medical Research

The ICMR has warned that its data are inadequate. “Please note this data is only from clinics who sent their information to us and is not comprehensive. In fact, these figures should not be used as indicative of the country, as the registration was not mandatory,” Soumya Swaminathan, director general of ICMR, told IndiaSpend in an e-mail.

The Indian government had roped in the ICMR to set up a national registry after the framing of the 2010 bill. The bill was brushed up by the current government last year and presented as Assisted Reproduction Technology (Regulation) Bill 2014. And then, according to an ICMR official who did not wish to be named as this person is not authorised to talk to the media, the surrogacy bill was introduced without any consultation with the nodal agency. IndiaSpend could not corroborate this statement.

The fresh surrogacy bill has been widely debated for multiple reasons. The bill bans commercial surrogacy; it allows only women within the family of an infertile couple to play surrogates. Foreign nationals and single parents cannot look for surrogacies either.

Over the nearly two years when data were collected, there was no case of a single parent asking for a surrogate, according to data available with ICMR. Also, only 40 foreign couples asked for permission to use surrogates in India.

The now-dormant national registry, as per the original plan, was to have a staff of 18, including scientists, to collect and store varied data--in the case of IVF, the type of treatment sought and the outcome, the age of the woman who signed up for the treatment and the number of cycles undertaken. In surrogacy, the data would have included the age of the woman contracted to carry the baby, her treatment and payment.

A policy would then have been framed using these data, bringing greater transparency to the ART industry. There were reports of at least two women dying while they were undergoing IVF treatment, neither case was investigated thoroughly.

Any legislation on ART must include wider issues that confront medical practitioners, said Sudhir Gupta, head of forensics at the All India Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS). He cited the case of a dead man’s wife seeking post-mortem sperm retrieval and added that he has had to deal with more such requests in the past.

“We have never done it (post-mortem sperm retrieval) because these are emotional decisions, requests that are made in the heat of the moment. Also, ICMR has not given clarity on this,” said Gupta.

Elsewhere, countries put out regular data on ART. The United States’ 2014 Fertility Clinic Success Rate report concluded that 1.6% infants born in the country were conceived through assisted reproduction. This annual report allows scrutiny and ranking of the busiest IVF clinics.

IVF clinics in India are mushrooming--one even advertises an EMI scheme on FM radio. The cost of treatment per IVF cycle is anywhere between Rs 1.5-Rs 2.5 lakh and an estimated 55% of treatments take place in eight metros, according to a 2015 report by Ernst & Young. The report also concluded that the absence of a regulatory framework leads to poor treatment outcomes and patient care. The compound annual growth rate of the market catering to infertility, according to the report, is 18%.

(Kalra is a Delhi School of Economics alumnus and freelance journalist whose former employers include Reuters, Mint and Business Standard.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”