Why Pundalikrao Ukarde Does Not Want To Raise Cows Anymore

Two cows and two calves in the stable near farmer Pundalikrao Ukarde's house in Karmad village, Aurangabad taluka and district, Maharashtra. "About a decade ago, we owned more than 10 cows and buffaloes. Now, we just have two cows," Ukarde said. (Photo: Poorvi Kulkarni)

In this second of our two-part series on why small farmers in Maharashtra are upset with the new restrictions on cattle trade for slaughter, we visit two cultivators in Aurangabad and Latur to understand the place of livestock in the agrarian cycle

In Karmad village of Aurangabad taluka and district, Pundalikrao Ukarde is sowing black gram in his field with a pair of bullocks to help him plough the soil.

Punadlikrao Ukarde ploughs his field with the help of bullocks and releases seeds through the seed-drill. It takes three hours for Ukarde to till half an acre of his one-acre black gram field in Karmad village, Aurangabad taluka and district, Maharashtra.

He is 61 but the hard work doesn’t appear to exhaust him. He has just tilled one row when his indigenous seed-drill, which ploughs the soil and also releases seeds into it, breaks.

Ukarde unscrews the tool and in about 15 minutes ties up the discs, tightens the screws and fixes the tilling rods upright. He works another three hours. “This is a crucial time. You won’t find anybody in the village idle,” he said.

Farmer Pundalikrao Ukarde fixing the seed-drill with the help of his son Shivkumar. The drill broke while he was sowing seeds on one-acre black gram field in Karmad village, Aurangabad taluka and district, Maharashtra. “This is a crucial time. You won’t find anybody in the village idle,” Ukarde said. After all this effort, once the crop is ready in 5-6 months, he will earn an average of about Rs 100 per-acre yield.

After all this effort, once the crop is ready in 5-6 months, he will earn an average of about Rs 100 per-acre yield. In the kharif season, Ukarde cultivates cotton, black and green gram over three acres of his five-acre land. On the remaining two acres, he grows vegetables and pomegranates.

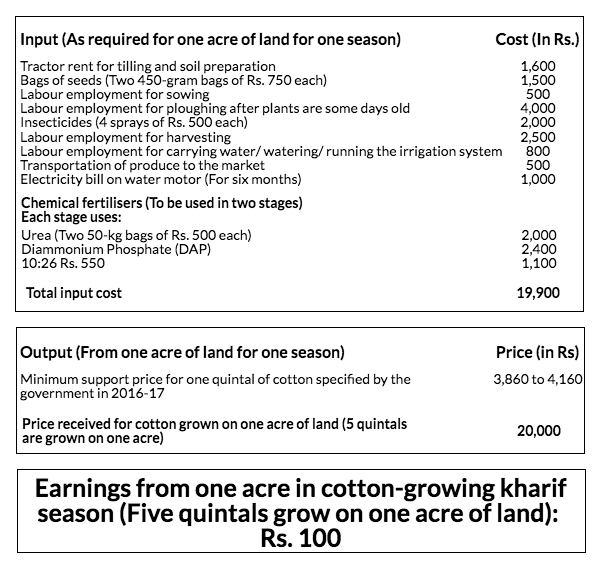

Cost Of Production Of Cotton On One Acre Of Land

Source: As estimated by Punalikrao Ukarde, former deputy sarpanch of Karmad village, Aurangabad taluka and district

Once Ukarde has accounted for the cost of seeds, fertilisers, pesticides, water, equipment and labour costs and deducted that from the price per quintal he will earn from selling cotton and green and black gram on his three-acre farm, he has about Rs 1,000 left in hand per year. This includes the income from wheat and jowar that he cultivates on the same patch of land in the rabi season.

Left to right:A sack of black gram seeds, kept for sowing, mixed with fertiliser diammonium phosphate (DAP) on farmer Pundalikrao Ukarde's one-acre black gram field; farmer Pundalikrao Ukarde and his wife Kantabai outside their house in Karmad village, Aurangabad taluka and district, Maharashtra.

“How do we take care of our health, our children’s education and all other living expenses with this amount?” asked Ukarde whose family of seven depends entirely on agriculture for income.

There was a time he earned much more from selling the milk from his stable of more than 10 cows and buffaloes. The manure from the livestock was used to enrich the fields. Today, Ukarde’s cattle shed is mostly empty. He has just two indigenous cows that yield about 1-2 litres a day, just enough for the family.

Most people in the village had at least six buffaloes through the 1990s and early 2000s, he recalled. The village also ran a dairy cooperative – Jay Bajrang Sahakar Tattva Milk Dairy Society – that supplied around 450 litre of milk every day.

However, over the years, the government barely raised the procurement price for milk just as it didn’t for crops, pointed out Ukarde who headed the cooperative society for seven years.

Finally, the cooperative society started incurring losses and had to be sold off to a private company because of the losses it incurred.

“Even those in the village who supplied milk are now buying packaged milk for themselves,” he said.

Successive droughts not only failed crops, but also destroyed the self-sustaining economy of the village.

An 8,000,000 litre-capacity pond that Ukarde got constructed near his farm has not filled in the past three years.

A 8,000,000 litre farm pond that Punadlikrao Ukarde got constructed seven years ago near his field in Karmad village, Aurangabad taluka and district, Maharashtra. "The pond hasn't filled in the past 2-3 years because of drought. We have had to buy tanker water to water our crops," he said.

“The well too had run dry and there was not enough water to even drink for us. We had to buy tanker water to water our crops,” he said.

With some water storage infrastructure, he had switched to growing pomegranate on one acre seven years ago.

An acre can grow 200 trees and each tree gives about 20 kgs of pomegranate. “Pomegranate is the only profitable crop which has helped us sustain in the occupation of agriculture. It is because of this decision that I have been able to save Rs 1 lakh,” he said.

“But the crop requires a lot of water. And, in times of drought, with less water in wells and pond, the cost for pomegranate farming increases a lot. Apart from drought, natural disasters like hailstorm and even pests cause unwarranted losses”.

Amidst such duress, it was a common practice to keep only productive animals and sell them off once they got old. “We are willing to leave all our cattle in their homes in the cities. They can take care of them as they want,” Ukarde retorted when asked about the government’s new rules on cattle sale.

As he struggled to fix his spectacle lens into its broken frame, Ukarde said he hoped for a day when farmers would get just prices for their produce. “It doesn’t matter if it is the BJP or Congress or Shiv Sena or NCP in the government. Aamhaala aamchyaa ghaamaacha daam milala pahije (We must get the price of our sweat),” he said.

Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis had recently stated that “cow protection” -- and thus curbs on cattle sale for slaughter -- is key to averting agrarian distress and farmer suicides. But it is clear from how livestock is actually used by farmers like Ukarde that in a drought crisis of the kind Marathwada repeatedly sees, farmers cannot afford to stick to the terms of the new cattle market regulations.

As IndiaSpend discovered during its travels in interior Marathwada, these regulations – and the red tape they stipulate -- have resulted in the slowing down of trade in the once-busy small animal markets of Marathwada. Both farmers and traders are now staying away from these markets.

Neelkanth Chimandare, 65, a farmer from Patilwada, a hamlet off the bustling Hali-Handarguli village in Latur district pointed out that most small agriculturists hardly have any resources to maintain unproductive cattle.

He estimated that a bull consumes a minimum of 50 litres of water and 20 kg of fodder a day. This needs an acre of land to raise fodder for four-five animals.

“Many do not have resources to grow fodder or jowar (the husk of which is also fed to cattle). They have to buy it from others,” Chimandare said.

He is exasperated by questions about how much it costs him to feed his cattle. They are like his children, he said. “We don’t measure the feed we give our cattle. It is only the gaushalas (cow shelter camps) and other cattle-breeding units that have stipulated fixed amounts of water and fodder,” he said.

Chimandare, who owns two bullocks, said that despite mechanisation, they are still useful for farming. “Tractors can only be used for tilling before sowing, but sometimes they are not available on rent. And, for ploughing after plants are some days old, only bulls can be used to loosen the soil,” he said.

(Kulkarni is a Mumbai-based freelance journalist, who has worked with Haqdarshak--a social enterprise, Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan--a non-party people’s political organisation and Hindustan Times--a newspaper.)

Series concluded. You can read the first part here.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”