Why India’s Social Capital Experiment Is Flailing

On the face of it, India does not have a runaway unemployment problem. But the figures can be misleading, particularly since organised labour constitutes barely 7% of total labour. Nevertheless, if you were to go with figures put out by the Government, unemployment is currently (and only) at 6.6%.

On the face of it, India does not have a runaway unemployment problem. But the figures can be misleading, particularly since organised labour constitutes barely 7% of total labour. Nevertheless, if you were to go with figures put out by the Government, unemployment is currently (and only) at 6.6%.

In recent years, the Government has attempted to address the job problem through several schemes. One of them is the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), started in 2005 with the idea of giving Rs 100 per working day to unskilled rural workforce. With effect from April 1, 2013, the maximum wage is Rs 214 in Haryana and the minimum is Rs 135 in the north-eastern states.

In 2011, another scheme called the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) was launched to touch rural India and build livelihoods. The idea was to fight poverty through the creation of social capital, a concept credited to political scientist Robert Putnam.

Interestingly, the original scheme dates back to 1999 and was called the Swaranjayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojna (SGSY). After running it for a decade, the Government found that large states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar were lagging in implementation. In 2011, the SGSY was rechristened as the NRLM with greater autonomy to states in formulating their programmes.

The Government has allocated Rs 3,659 crore for the NRLM in 2013-14, an increase of 54% from Rs 2,373 crore last year. Total funds under the SGSY for the years 1999 to 2007 were Rs 16,188 crore out of which Rs 11,963 crore were utilised. The figures are from a Ministry of Rural Development report that suggested revamping the SGSY into the NRLM.

As anyone following India’s Budget exercise would know, the Government has been steadily increasing its allocations to MNREGA (Rs 33,000 crore in 2013-14 - last year it was Rs 29,387 crore ) and has also faced severe criticism, largely on grounds of distorting labour markets and creating a culture of entitlement. The NRLM is different in some ways because it encourages individual enterprise. But how effective has it been?

A quick description first - The NRLM attempts to make at least one member of every rural, below poverty line (BPL) household become part of a Self Help Group (SHG). An SHG is a block of 10-20 people organised for community support. SHGs are linked to banks for formal credit support to ensure financial inclusion for the members. Capacity building, training and ensuring skilled wage employment are also ensured by SHGs.

Beneficiaries are trained in a range of activities that could add to their income including handicrafts, poultry farming, horticulture or computer skills. Now, let us look at how the scheme has worked across the states of India with high rural poverty.

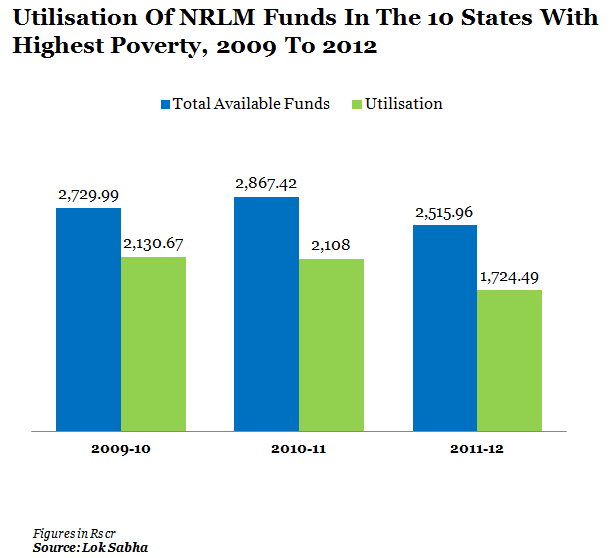

Figure 1 (a)

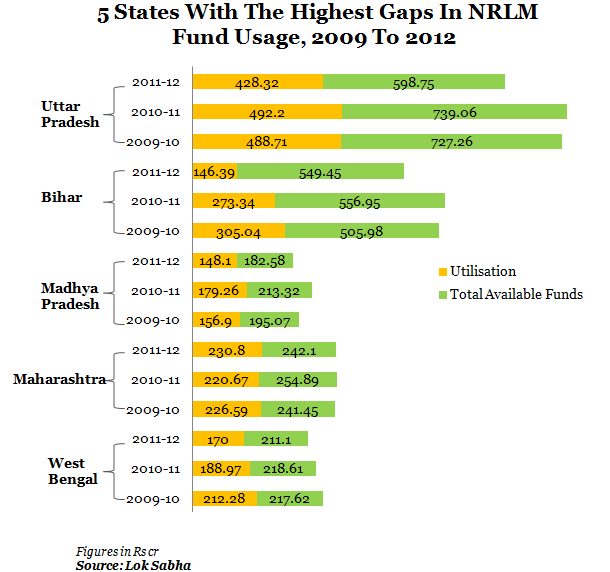

Figure 1 (b)

It is evident from the table above that most states are not using the funds available to them to run NRLM. And the quantum of unused funds only seems to be rising every year. From Rs 600 crore in 2009-10, the figure has increased to Rs 1,543 crore in 2011-12.

The larger finding seems to be that the scheme struggled in areas where the rural population was high. Particularly because, for various reasons, the SHGs were not being formed or could not be formed.

For instance, the rural BPL population in the northern and eastern states comprises about 63% of India’s rural BPL population. However, only 40% of all SHGs formed were in these two states. On the other hand, only 11% of the rural BPL population is in the southern states but they host more than 33% of total SHGs.

A reminder: SHGs are small self-motivated groups which would have the ability to borrow money from banks and use it for some joint economic activity. No SHG, no capital (under the scheme).

Let us now look at state-wise data on targets and achievements on self-employment:

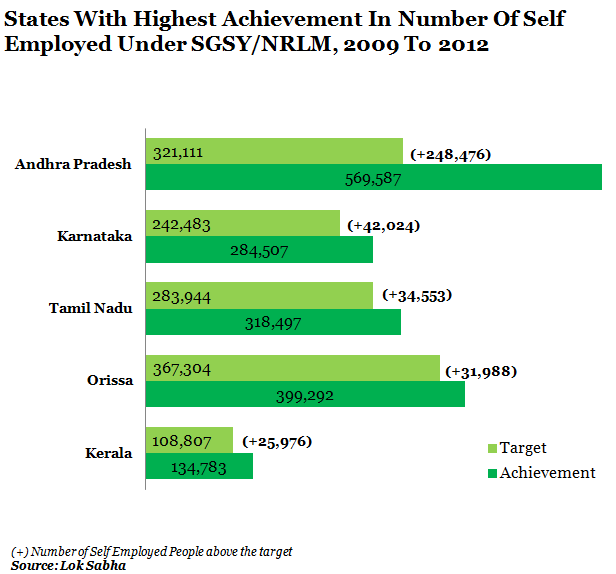

Figure 2 (a)

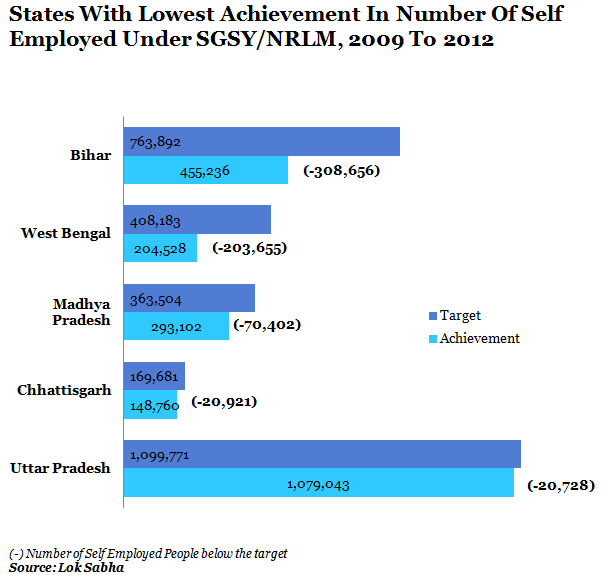

Figure 2 (b)

The data shows the gaps in performance between the top five states and the bottom five states. While all the best five states generated more self-employed people than the set targets, states like Bihar and West Bengal lagged considerably.

One reason could be the involvement of women in SHGs... almost all the southern states of the country had more SHGs led by women... the policy challenge, therefore, could be to ensure more women participation in programmes like NRLM. There is, of course, the final question on outcome. And more fundamentally, is this experiment of using social capital to fight poverty working? The answer, so far, is clearly very mixed.