Why Indian Banks Want To Invest In A Rs 8,500-Crore Bad Debt

Invest money to recover lost money.

That is the mantra some of India's biggest banks are following as they try to attract a buyer for a part of the 22-year-old infrastructure of the Ratnagiri Gas and Power Project Ltd (RGPPL), formerly known as Dabhol Power, built by now-collapsed and disgraced US energy multinational Enron.

Sprouting from the sylvan Konkan coast, 160 km south of Mumbai, are the soaring but silent towers of what was once a state-of-the-art 1,967-MW power plant running on natural gas—projected to meet 3% of India's energy needs—but now a giant debt burden that could further destabilise India's shaky banking system.

Idle since April 2014, Ratnagiri Power and Gas has unpaid debts of Rs 8,500 crore, much larger than the Rs 6,500 crore that high-profile defaulter Kingfisher Airlines owes banks. If a solution cannot be found to Ratnagiri Power and Gas's outstanding debts, it will be an important symbolic failure, apart from directly boosting the Rs 2.68 lakh crore ($42 billion) of unpaid, overdue loans (as of September 2014) that companies owe the Indian banking system.

Source: Lok Sabha

The major part of this system is owned by the Indian government, which means any loss is eventually made good by the taxpayer.

The State Bank of India, ICICI Bank and Canara Bank are among the lenders who have offered to invest Rs 1,200 crore to expand and revive the power plant's liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal and hive it off as a standalone facility, the Economic Times reported. Promoters, however, are not very happy with the idea. According to a separate Economic Times report, the promoters felt the plan puts an unfair financial burden on them and only protects lenders' interests.

The chances for restarting the power plant are dim. India’s domestic natural gas production isn’t enough to supply fuel to gas-based power projects, such as Ratnagiri Gas and Power.

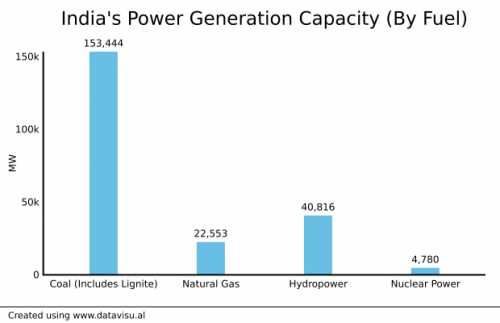

It isn’t the only project suffering: India has 22,553 MW of capacity in over 50 gas-fired power plants, which make up 10% of the country's generating capacity, collectively operating at less than a quarter of their capacity due to fuel shortages.

Using a ball-park figure of Rs 3.5 crore loaned per MW, this capacity represents an investment of Rs 78,000 crore that can go bad. Approximately one third of this capacity is with private-sector infrastructure firms, such as Torrent Power, Lanco, GVK and GMR, many of whom are highly indebted; some are in dire financial straits.

If any of these loans become non-performing assets (NPAs), representing unpaid loans, it could further imperil a banking system increasingly anxious about rising NPAs.

As long as these plants are idle, this is a clear risk. Apart from the potential financial problems, this is also an environmental issue. Natural gas is much less polluting than coal, and more gas-based power can help bring down India’s carbon footprint. Under the current circumstances, that seems highly unlikely.

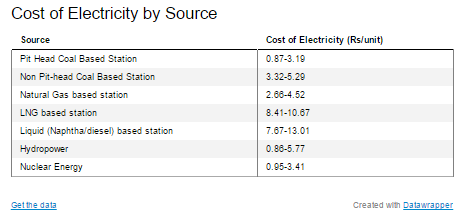

India could import natural gas in liquid form, LNG, to fuel these plants. However, LNG prices are much higher than domestically produced natural gas. Electricity produced using imported LNG is very expensive, between Rs 8.4 and Rs 10.67 per unit, going by historical prices.

Source: Lok Sabha

Source: Central Electricity Authority, Installed capacity as of Nov. 2014

Dabhol's dubious legacy

Dabhol was built in 1992 after Maharashtra promised to buy the plant's expensive energy, whether it used the electricity or not. The Central government guaranteed payments if the state defaulted on loans.

"The agreement was negotiated secretly, because policy makers and company officials said it would be faster that way," the New York Times reported. "The deal promised the company a guaranteed rate of return in dollars, which meant that the price of power to India would most likely rise because the government was depreciating the rupee against the dollar.

"To make the project’s math work, the state would have to jack up retail power prices and crack down on theft of power; neither of which happened. Maharashtra ended up paying Enron Rs 4.67 for each unit of power, even though it was collecting only Rs 1.89 from its customers."

Enron withdrew from Dabhol in 2002. Three years later, Ratnagiri Power and Gas was set up to restart the plant, with the public-sector National Thermal Power Corporation, India's largest power company, Gas Authority of India Ltd, Maharashtra's electricity board and financial institutions as shareholders.

As long as the plant stays shut, the company earns no revenue and cannot repay lenders. However, if assets with revenue-earning potential are spun off, the banks can still recover some or all of their loans. And, so, the proposal to expand and restart the LNG terminal.

What Dabhol's LNG terminal could do

While LNG is too expensive to be used as fuel for power generation, it can be used for automobiles and industries.

For instance, Delhi and Mumbai have more than a million vehicles using compressed natural gas (CNG), another form of natural gas, as fuel, instead of diesel or petrol.

Apart from being cheaper than liquid petroleum, natural gas is also less polluting. The government now hopes to sell , Hyderabad and Pune and expand imports.

India already imports over 10 million tons per annum of LNG. With India's natural-gas consumption a tenth of the global average, these imports are set to grow sharply.

Ratnagiri Gas and Power's co-promoter, GAIL, which builds gas pipelines and markets natural gas, has signed deals with US and Russian companies to bring in more than 8 million tons of LNG into India, in addition to current imports.

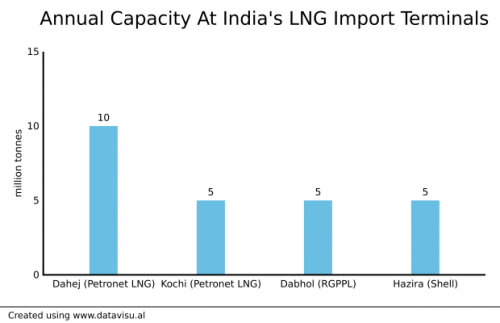

Bringing this gas to India will require shipping terminals, such as the one at Dabhol. India currently has four LNG terminals, with more on the drawing board. Clearly, there is demand for this infrastructure.

Source: Chemtech Online

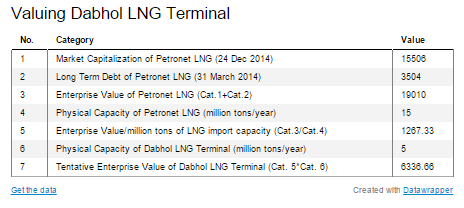

There is already one listed company, Petronet LNG, set up to import LNG. Petronet operates two LNG terminals, at Dahej in Gujarat and Kochi in Kerala, with a combined capacity of 15 million tons per year. Using Petronet LNG as the basis, the tentative value of the Dabhol LNG terminal works out to Rs 6,337 crore, enough to cover almost 75% of Ratnagiri Power and Gas's bank debts. Discount Petronet LNG's value by 10% and more than 60% of the project’s dues can still be recovered.

All figures in Rs crore except LNG terminal physical capacity

With India's economy continuing to be weak, the bad debts of the banking system won't be repaid any time soon. Resolving high-value cases, such as Ratnagiri Gas and Power, to allow the recovery of at least a part of these debts, can at least mitigate the problem.

Image Credit: Flickr/Ankur P

_______________________________________________________________

our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”