US Position On India’s Subsidies To Farmers Has ‘Infirmities’: Trade Expert

Mumbai: The July 2018 announcement of minimum support prices (MSP)--or subsidies that the government pays the farmer--for the kharif (monsoon) crop may see a battle at the World Trade Organization (WTO) between India and the US for breaching WTO subsidy limits, which are not supposed to exceed 10%--compared to the 60% to 70% that India appears to be paying its farmers.

The US accused Indian agricultural subsidies to be “vastly in excess”, according to this June 2018 note from the International Centre For Trade and Sustainable Development, a nonprofit organisation focussed on sustainable development through trade-related policymaking.

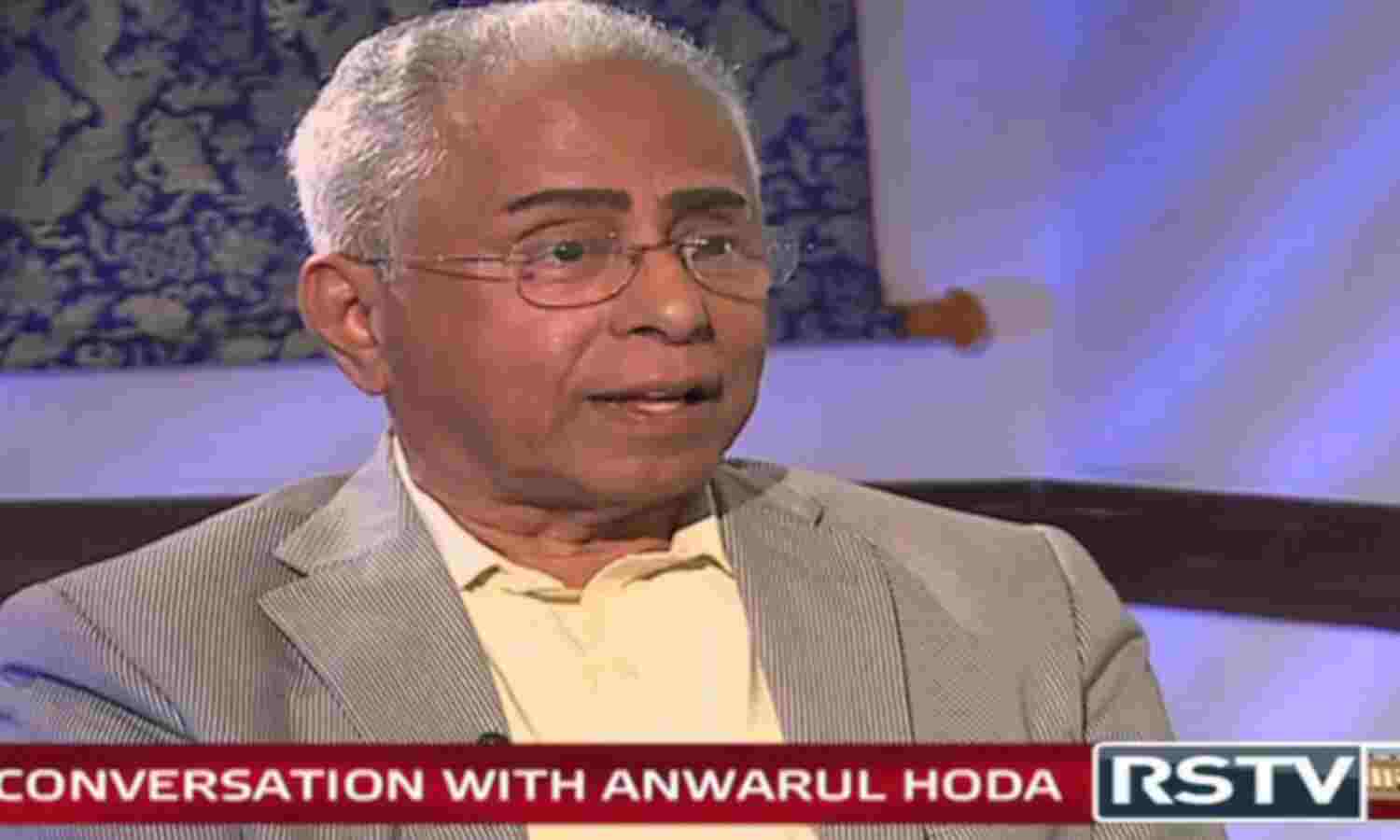

Anwarul Hoda, 79, chair professor of Indian Council for Research On International Economic Relations’s (ICRIER) trade policy and WTO research programme, says that there are infirmities in the US’s calculations as it does not account for inflation, among other factors, and that the three-decade-old framework has to be updated to resolve similar problems related to trade between developing and developed countries.

Hoda, a former civil servant from the Indian Administrative Service, has worked extensively on trade policy having worked in the ministry of commerce between 1974-81 and 1985-93. He played a significant role in multilateral trade negotiations under the general agreement on tariffs and trade (GATT), and was the chief policy coordinator of the Centre during the Uruguay Round (1986-93) of GATT.

Hoda was the deputy director general, WTO, and chaired the legal drafting committee for the WTO agreement, the tariff committee for the verification of the results and the committee on the information technology agreement. In five years to 2009, Hoda was a member of the Planning Commission in the rank of minister of state in the union government.

In an email interview to IndiaSpend, Hoda shares his concerns about global trade that seems to be “spiraling out of control” due to peremptory trade measures and retaliatory responses, led by the US, and talks about income support to be introduced to ensure farmers can be protected from price fluctuations.

You wrote in an opinion piece on the WTO Buenos Aires Ministerial that the “vision is missing, political will is lacking and a constructive approach for seeking compromise solutions is absent”. Do you believe that the multilateral world bodies such as the WTO have lost their relevance? What is needed to revive and strengthen itself to resolve multiple trade disputes effectively?

Multilateral rules of world trade are as relevant today as they were earlier, and I think all trading nations, except one, continue to have faith in the multilateral trading system. The economically weaker countries have a greater stake in the system as it protects them from arbitrary and unfair trade action by stronger partners.

Besides, non-discriminatory trade rules are best in economic terms as they ensure that economic operators buy from the cheapest source and sell in the dearest market.

Unfortunately, the present US administration has declared its preference for bilateral agreements in the belief that it would be able to obtain greater concessions from trading partners by virtue of its superior economic (and military) strength. The assumption on which the US has based its policy will be tested in the retaliatory and counter-retaliatory moves being exchanged among major trading nations in which we might see the denouement sooner than later.

I think the time has come to hold serious high-level discussions among major trading nations to quell the dangers that threaten the multilateral trading system. No change is necessary in the dispute settlement machinery, except to eliminate the veto that individual WTO members have on the appointment of members of the appellate body. What needs to be done to revive and strengthen the dispute settlement machinery is a sincere reaffirmation by the WTO members of their faith in the system and their determination to abide by the rules.

The US has stated that India gives 60%-70% higher subsidy for rice and wheat against the stipulated 10%. With the US taking up the issue at the WTO, how is it going to affect farmers for whom the government is planning to provide minimum support price (MSP) at 150% of cost of production?

We first need to understand the method of calculation of subsidy envisaged in the WTO rules and its underlying rationale before we can come to a conclusion on the validity of the US claim.

For product-specific support, such as the MSP and the related procurement operations in India, the starting point for the rules was the calculation of the annual level of support (the aggregate measurement of support or AMS) for each product in the base period, which was agreed as 1986-88. The product-specific AMS was calculated by multiplying the difference between the international price and the applied administered price (support price) by the quantity of production that was eligible for the support price.

The non-product-specific AMS was calculated by adding up all support such as subsidies on fertiliser, power and irrigation in India. Rules also provide for the calculation of equivalent measurement of support for products where subsidy exists but the calculation of the AMS is not practicable.

Product-specific AMS, non-product-specific AMS and the equivalent measurement of support were then aggregated to give the total AMS for each member. The members agreed to reduce AMS by 20% for developed countries and 13.33% for developing countries in the implementation period, which began in 1995, as six years generally and 10 years for developing countries.

We need to take note of two specific features of the rules that have a bearing on India’s obligations arising out of the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). First, there is the concept of de minimis, which was set at 5% for developed countries and 10% for developing countries. If the product-specific support was less than 5% of the value of production of the product or if the non-product-specific support was less than 5% of the entire agricultural production, the support was not taken into consideration for the purpose of calculation of the total AMS. For developing countries, it was 10%. Flowing from this is the obligation that if a member has no AMS commitments, as in the case of India, it has to ensure that its product-specific AMS does not exceed 10% of the value of production in any year.

Second, for the purpose of calculation of product-specific AMS, the international price prevailing in 1986-88 was also adopted as the fixed external price for future years. In some of the developed countries, for many products, the applied administered price was far higher than the international price prevailing at that time, and the agreed reduction of 20% did not bite substantially in the product-specific AMS. These countries were the real targets of the rule on a fixed external reference price and the idea was to squeeze their subsidies by subjecting their total AMS to erosion by inflation.

It was clear at that time that for developing countries with no AMS commitments, and particularly countries in which the support was negative and the price was less than the external reference price during the base period, it would not be appropriate to ignore inflation. It was for these countries that Article 18.4 was introduced, providing that “members shall give due consideration to the influence of excessive rates of inflation on the ability of any member to abide by the domestic support commitments”.

The calculation made by the US has two infirmities. First, it adopts the MSP as the applied administered price for 2011-12, 2012-13 and 2013-14 as the starting point and subtracts from it the fixed external reference price notified by India, without taking inflation into account. It completely ignores Article 18.4 of the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA).

Second, it errs in mechanically applying the conclusion reached by the appellate body in the Korea-Beef case that "eligible production" means all the production entitled or permitted to receive the administered price.

No doubt AoA has, as a general rule, set the fixed external reference price in nominal terms. In doing so, the idea was to deal with the problem that in the industrialised subsidising countries that used market price support, the prevailing support price in 1986-88 was far in excess of the external reference price, and the agreed reduction of 20% in domestic support was making only a small difference to the level of subsidy.

For example, in the EEC (now the EU), the intervention price (the applied administrative price) for common wheat was 203.4 ECU/metric tonne [European currency unit, now replaced by Euro] against the external reference price of 86.5 ECU/MT. For rice, the intervention price was 356.1 ECU/MT and the external reference price 143 ECU/MT.

The situation was very different in the case of members like India. In their case, the external reference price at that time was more than the applied administrative price. For wheat, the MSP was Rs 1,740/metric tonne, which was lower than the external reference price of Rs 3,540/MT. For common rice, the MSP was Rs 2,280/MT, lower than the external reference price of Rs 3,540/MT.

Thus, in the case of both wheat and rice, the support was negative in India. In other words, India taxed these crops rather than subsidising them. Obviously, a correction was required in the applied administrative price for the year-to-year inflation for global comparison.

It is to allow for such correction that Article 18.4 of the AoA provides for the members to give due consideration in the committee on agriculture when the notifications made by members are reviewed. Obviously, the US should have also made due allowance for the influence of inflation, which it has not, and for this, the US calculations are deeply flawed.

As regards eligible production, one needs to look at the WTO jurisprudence to come to a firm conclusion. There is no doubt that for the coherence of the system, the rulings of the appellate body need to be adhered to in future cases in the WTO. However, the jurisprudence recognises that for cogent reasons, departures from past rulings may be needed. The question to ask is whether there are cogent reasons for the entire production not to be considered as eligible production in the case of wheat and paddy in India.

We need to consider that many states are not well organised to procure all the produce as they have neither the infrastructure (warehouses) nor the personnel in position for this purpose. As a result, in several states, the prevailing domestic price is below the MSP. There is also the question that much of the production is retained by subsistence farmers for consumption and for seed purposes and the marketable surplus is a much smaller quantity than full production.

It also needs to be mentioned that there are 23 commodities for which the government fixes MSP annually but the support operations are carried out regularly in respect of only wheat and paddy, and that too principally in three major producing states. In other products, the price support operations are sporadic or not carried out at all.

For all these reasons, the actual quantity procured is the only safe bet for determining the eligible production for major staples in India.

Until recently, the increased MSP broadly took care only of inflation. The future may be different, particularly in view of the central government’s decision to fix MSP on the basis of the cost of production plus 50%. In view of the large increase announced recently for the 2018-19 kharif crop (monsoon crop), it may be difficult to ensure that we keep within the limits of our WTO commitment (product-specific AMS does not exceed 10% of the value of production of that crop in any year).

Apart from difficulties in abiding by international treaty commitments, India might face economic and fiscal challenges if it is unmindful in fixing MSP without regard to the prevailing international price. Procurement of crops at rates higher than international prices may result in a situation in which the government is saddled with large stocks and it will not know what to do with these overpriced stocks.

I must also add that the WTO framework of rights and obligations, which was negotiated 25 years ago based on 1986-88, is outdated and becoming irrelevant in a changing world. The WTO members need to renegotiate the rules on domestic subsidies urgently.

The calculation of aggregate measurement of support based on the base period of 1986-88 has been an issue for India and other developing countries at the WTO. In this article, you mentioned that “unless full adjustment is permitted for inflation, India would have to bring down its MSP to within 10% of the external reference price of Rs 3,520 [for rice], that is Rs 3,872”. What are the consequences of this on public stockholding of grains, which is vital to ensure effective food availability under the public distribution system?

I would like to add that there is no threat to stockholding operations in India as there is no limitation if procurement is done at the prevailing market prices. The whole problem in India is that procurement for stockholding operation is carried out indistinguishably from the subsidy operations.

In its proposals, India is in reality seeking flexibility for increasing producer support rather than for raising consumer subsidies. There is no threat to public stockholding of food grains or the public distribution system as long as the procurement of food grains is done at market rates. Since the issue prices [prices in ration shops] for the public distribution system are heavily subsidised and are completely disconnected from the MSP, there is no need to keep the two prices and operations linked.

The US is reported to provide $50,000 per capita to farmers as subsidy compared to $200 per capita annually in India. With developed countries such as the US and the EU sustaining such iniquitous rules that provide massive subsidies, what must India do to ensure parity in the present circumstances?

There is no agreement at present which recognises per capita agricultural subsidy as the basis for international rules but the chasm that exists in the per capita agricultural subsidies between the developed and developing countries does raise a question of equity. A more rational basis for the purpose of comparison could be the subsidy per acre or hectare of cultivated land or subsidy per cow in a dairy. These figures can be used for the purpose of argument rather than for developing meaningful disciplines.

Over the last year, there has been price fall caused by the glut in crops such as potato, dal, garlic among others. How have these incidents affected the agriculture economy and trade in and outside India?

Rise and fall of agricultural prices have been happening from times immemorial. The proper thing for the farmer to do is to heed market signals and produce more or less, depending upon whether the prices are rising or falling. The government can intervene only to a limited extent in assuring fair prices for farm produce. In India so far, the government has done so only for the major staples, wheat and rice.

Extending subsidy to more products on a regular basis will take the government on a slippery slope. Last year, the government went in for subsidy for pulses and accumulated a stock of 5 million metric tonne. Today, the government does not know what to do with the stock.

Major agricultural producing countries have moved away from subsidy towards decoupled income support [support for farmers that is not linked to prices or production]. This is what India will need to do in future. It is important to ensure that income support to be introduced in future subsumes existing programmes for price support and input subsidies.

There has been a rise in protectionism the world over with US and China increasing import tariffs for goods such as automobiles and tech innovations. Do you think India can benefit from the trade impasse or will it have a detrimental effect on India and international trade overall?

It is not adequate to describe the current state of affairs as a mere rise in protectionism. The world trade situation seems to be hurtling towards chaos. In the extremely unstable environment created by the peremptory trade measures introduced by the US and the ad-hoc retaliatory responses from other trading nations, it would be foolhardy for any country to try to use any temporary trade opportunity that might be created.

Expansion of trade can take place only in an atmosphere of stability and predictability in which trading nations have confidence of continuity. Only then can they make investments to produce goods for which they see a market emerging. Not many months ago, I had hoped that after initial trade skirmishes, normalcy would be restored and world trade would settle down. Contrary to my expectation, the circle of retaliation and counter-retaliation looks like spiralling out of control, which can bring the entire world economy down. The July 25, 2018, agreement between the US and the European Union not to take trade action against each other and enter into negotiations for reduction of non-auto tariffs has, however, given a glimmer of hope.

India has increased customs duties for products such as electronics, furniture and other goods in the recent budget to encourage domestic products through Make in India. How do you see such measures affecting India as it attempts to incentivise domestic manufacture?

In my view, raising customs duties to enable increased domestic production of industrial products is the wrong way of going about it. This is what we had tried to do in the years prior to economic reforms and failed. When we started reducing our tariffs in 1991-92, initially, the high-cost manufacturing industries suffered a shock but gradually their performance improved while the protective tariffs were being reduced drastically.

In 2004-2008, exports of manufactured goods from India increased impressively even as the peak duties on such goods were progressively lowered from around 20% to 7.5%. India emerged as a major exporter of automotive components and pharmaceuticals.

If manufacturing costs in India are higher today compared to China it is because of a number of factors that have a price-raising effect. Power supply has been improving but it is still deficient in that there are interruptions in supply and even when supply is made it is of poor quality.

In modern times, manufactured goods are not wholly manufactured on the floors of a single factory. These are the days of international production-sharing and parts and components have to be imported, and sometimes, they have to move several times across international borders and within the country. Unless India has world-class logistics infrastructure, ports, airports, roads and rail, it will lag behind peers in competitiveness. There should not be long lines of trucks waiting for hours to load or unload the containers at the ports.

It is also important that the customs procedures are as simple as possible and do not take a lot of time. Labour laws have to provide for a modicum of flexibility in hiring and firing and developed land needs to be provided to industrial units at competitive prices.

As India is internationally uncompetitive for a host of manufactured products, it is necessary to take action on all the fronts mentioned above on a war footing. The aim should be to make Indian manufacturers competitive rather than provide them shelter from competitive foreign sources.

Does it mean that tariffs should never be increased? No, tariffs may be increased in rare cases in order to protect domestic industry from serious harm. In fact, tariffs can even be increased temporarily on products on which India has taken a WTO commitment to bind the duty. In these cases, proper procedures have to be followed and India has to offer compensation. The case for not raising tariff on imports rests on economic good sense rather than on WTO commitments.

(Paliath is an analyst with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.