Rs 38,420 crore: Little Sikkim's Huge Growth Gamble

It is barely known, compared to its competing development paradigm, the Gujarat model, but the Sikkim way of economic growth is one of India's most successful.

A little more than double the size of Goa, the Himalayan state is one of India's most advanced, educated, healthy, prosperous and clean states. This year, it even became the first Indian state to have a toilet in every home.

It helps that Sikkim's reticent, often controversial five-time chief minister, Pawan Chamling, has been in power for 20 years, a time when the state's economy, sometimes, grew by 22%, while India's average growth was 8% (between 2007-08 and 2011-12). The poverty rate has also fallen by more than a fifth to 8.19%, in the six years to 2012. In two years, Chamling promises, his state will be free of poverty.

Source: Planning commission, GSDP:Gross State Domestic Product, Figures in %

In a state hard-pressed to provide employment—indeed, joblessness is a major problem, with one in nearly four persons between 15 and 29 years unemployed—35% of Sikkim's revenue comes from a unique source: water.

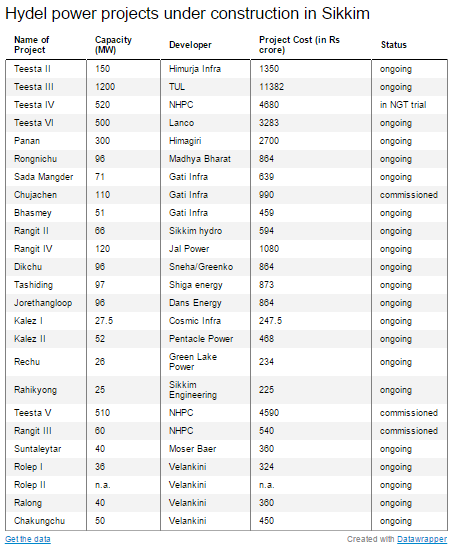

By 2015, Chamling intends for hydel power generated from a 175-km stretch of the Teesta river to earn Rs 900 crore every year as his state's share (between 12% and 15%) of 26 functioning and under-construction hydro-electric projects.

Source: Affidavit reply from Sikkim power and energy department to a PIL

The government owns between 12% and 26% of these projects; the other investors are a raft of private companies.

The data appears to make sense: Sikkim's own energy needs of 409 megawatts (MW) were met by 2012, and Chamling already sells 175 MW of extra power to India's power-starved northern grid. If all 26 hydel projects come on stream, Sikkim should generate 4,190 MW of electricity.

The problem is that this ambition is ecologically and economically controversial, with one affecting the other. Already, Sikkim has reduced its revenue-earning potential from Rs 1,500 to Rs 900 crore, primarily due to the effects of an earthquake in 2011.

Another argument against it is emerging through the feuds, cost overruns and growing debts of the state's sprawling hydel ambitions.

"Tell me, who is going to buy projects with so many bottlenecks, coupled with very small trading margins from the sale of power?," asked Sonam P Wangdi, Sikkim's former chief secretary. Banks and financial institutions, Wangdi said, were sensing that many hydel projects could become non-performing assets (NPAs) or bad debts.

Disputes, debt and bravado

In October this year, a dispute broke out between the private equity partners of Teesta Urja Ltd (TUL), the private-public company building the largest hydel project on the river, Teesta-III in north Sikkim, with the government as a partner.

Teesta-III is the lynchpin in Sikkim's grand hydel plans. It's been funded by a number of Indian and foreign financial institutions, including Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Everstone Capital. Sikkim may need only 15% of the energy it generates; the rest will be wheeled out across electricity-starved north India, as far away as Rajasthan.

Teesta-III's holding company, Varuna Investments, appealed to Union Power Minister Piyush Goel over constant delays and cost overruns.

In response, the Sikkim government, one of the shareholders in Teesta-III, said if the other equity partners left—and the implication was they were free to—the state would buy them out, increasing its share in equity from 26% to 100%.

"The state government is totally committed to getting the project commissioned by 2015," a senior official of the Sikkim Power Development Corporation told IndiaSpend, on condition of anonymity. "In a given situation, where other investors don't participate in subscribing to the equity, we are ready to pick up all the equity."

This appears to be little more than bravado. Sikkim already owes more than Rs 800 crore to the Power Finance Corporation, a specialised public-sector financier of power projects.

About 75% to 80% of the Rs 1,500-crore cost of the state's equity holding in 6 projects comes in the form of loans that need to be repaid, so it is almost impossible for Sikkim to increase its investment—without borrowing more money. The Sikkim government holds equity in only 6 projects out of the total 26 coming up.

Chamling does not grant interviews, and in response to an IndiaSpend interview request to power department secretary M K Subba, the Sikkim power department suggested filing a right-to-information request.

In a written statement to Parliament, Goyal said Teesta-III would be completed by 2015. After a series of delays, Teesta-III is now reported to be nearing completion.

So, can Sikkim actually generate Rs 900 crore every year from the power of its water? Here are the problems:

- For Sikkim to earn Rs 900 crore ($138 million), it needs to sell 3,000 million units of electricity. Assuming Sikkim gets a 15% share in electricity generated from these projects, annual power generation should be 20,000 million units.

- On an average, 1 MW of hydropower (all India) delivers 3.32 million units of electricity.So, to generate 20,000 million units, Sikkim needs 6,000 MW of hydropower capacity.

- Even if the government assumes half the revenue (Rs 450 crore) is from energy sales, while the other half is from dividend that the government gets via its equity in projects, Sikkim still needs 3,000 MW of installed capacity. This won’t happen before 2020.

The promise and reality of the Teesta

Sikkim's economic proposition comes from this data: the home of the swift, frothing Teesta can potentially generate 4,248 MW, of which 669 MW is ready through existing hydel projects. Another 2,322 MW of hydel capacity is under construction.

But these projects are beset with cost overruns, as this September 2014 report of the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) indicates. For instance, the cost of the Teesta-III project has nearly doubled, from Rs 5,702 crore to Rs 11,382 crore.

Nine other projects in the list show no difference between original and latest costs, which means the estimates have not been revised, although many projects are already delayed, such as the 500 MW Teesta-IV project being built by Lanco, a company already known for its unpaid loans to Indian banks.

The original completion date of Teesta-IV was 2012-13; it's now 2016-17. But the price, in the CEA list, has stayed at Rs 3,283.08 crore. As for Teesta-III, the project's own website says the project "is schedule (sic) to be commissioned in 2011-12."

With such messy realities, the debt-rating agency Investment Information and Credit Rating Agency of India (ICRA) has placed the loans to the Teesta-III project in the high-risk category.

Hydel power is a risky business, as P B Praveen Kumar, operations director of Dans Energy, developer of of two hydroelectric projects, pointed out to IndiaSpend. Typically, it takes eight years for a hydel project to start working, but inflation, clearance delays, rate of interest changes and natural calamities frequently lead to cost increases, said Kumar.

The shaky ground under the river

Many of the projects on the Teesta are run-of-the-river projects, such as the Teesta-III, which means they generate electricity from the force of river waters and do not need big dams or reservoirs.

What it does mean is forcing the river into tunnels, so that the water is sharply directed on turbines that generate electricity. This government estimate said that once these tunnels are completed, the Teesta will be forced underground for 52 km, or about a third of its length in Sikkim.

As IndiaSpend previously reported, the wisdom of building so many dams in an earthquake-sensitive zone has been widely questioned. All of Sikkim falls in what is called seismic zone IV; a rating of V carries the highest risk.

That questioning continues.

Even a central government advisory body strongly criticised the widespread violations and wisdom of having 26 hydel projects on a river that flows no more than 175 km from the north of Sikkim to its south.

"We learnt to our great dismay that absolutely no ecological considerations whatsoever was used in the process of determining the hydropower potential of river basins," the National Board of Wildlife expert committee said in 2013 after a tour of Sikkim's dam sites.

"We saw with shock the ongoing construction on Teesta III ...situated in one of the most ecologically sensitive areas of Sikkim," said the report, warning of "disastrous consequences" downstream from construction debris.

As Chamling's great gamble with the Teesta unfolds, and its big loans come due, the unique Sikkim model will come under greater scrutiny than ever.

|

Update: The table in the article has been revised to correct the status of two projects—Teesta IV & V.

Soumik Datta is a journalist based in Gangtok. He covers issues related to the environment and energy. His email id is dattauni@gmail.com

Additional research by Prachi Salve and Amit Bhandari

Image Credit: Anandoart | Dreamstime.com

________________________________________________________________________

public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”