New TB Infections Fall, But Drug-Resistant Cases Rise

A patient collects his medicines for tuberculosis from a Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) centre in Meethapur, 17 km south-east of the national capital. In 2016, India had 3.57% fewer cases of tuberculosis and 12% fewer deaths from it, but a 13% rise in incidence of drug-resistant TB.

Though the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that new tuberculosis cases in India fell in 2016, the number of drug-resistant cases increased, showing that India has a growing challenge in its fight against the disease.

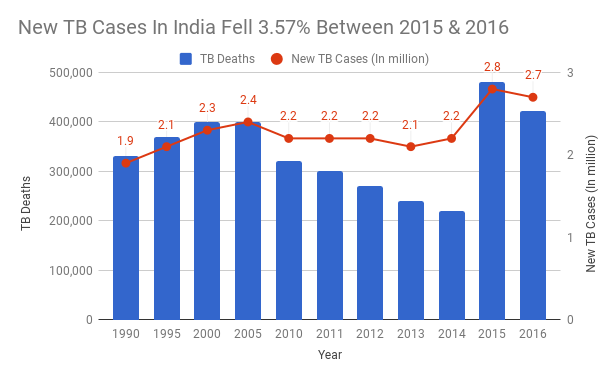

Deaths due to tuberculosis (TB) in India fell 12%--from 480,000 in 2015 to 423,000 in 2016, according to estimates from the WHO’s Global Tuberculosis report 2017. The number of new TB cases in 2016 that were drug-resistant--unresponsive to either one or both most potent TB drugs rifampicin and isoniazid--increased by 13%, from 130,000 to 147,000.

Drug-resistant TB takes longer--and is more expensive--to treat than regular TB.

Still, “these numbers are estimations”, and we are “not sure of the real burden of the disease until a national prevalence survey is completed”, said Soumya Swaminathan, director general of the Indian Council of Medical Research. “When prevalence surveys were done in other countries (such as Nigeria and Indonesia), the actual number of cases was much higher than what was estimated,” she explained.

“Estimates of TB incidence and mortality for India are interim in nature, pending results from the national TB prevalence survey (which calculated the total TB burden of the country including old and new cases) planned for 2018/2019,” the report cautioned.

In 2015, the WHO said India had double the number of estimated TB deaths--480,000 up from 220,000 in 2014--because previous estimates were too low, as IndiaSpend reported in October 2016.

Source: World Health OrganizationNote: The increase in cases and deaths between 2014 and 2015 can also be attributed to better counting.

India had 2.7 million new cases of TB in 2016, down 3.57% from 2.8 million in 2015, the WHO report said. One in four, or 26% of the 10.4 million new TB cases in the world were in India. Five countries--India, Indonesia, China, the Philippines and Pakistan--had the most new TB cases, making up 56% of all cases in the world, the report estimated.

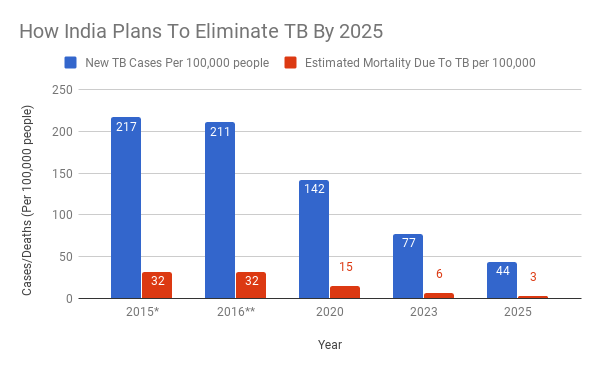

To achieve its goal of eliminating the TB epidemic in 10 years, by 2025, India would have to reduce new TB cases by 95% over the next decade, as FactChecker reported in March 2017. In comparison, India had reduced TB cases by 22% between 2005 and 2015, and 2.7% between 2015 and 2016, the new report showed.

Based on the estimations, “there has been a reduction in new TB cases but to meet TB elimination goals we need to reduce new cases by 10% every year”, said Swaminathan.

Source: World Health Organization, India’s National Strategic Plan for TB Elimination*Baseline; **Actual numbers

"The most important action is to notify every TB patient who is diagnosed and treated in the private sector to the National TB programme and support these patients with free diagnosis and free quality treatment," said Henk Bekedam, WHO Representative to India, in an email to IndiaSpend.

India has introduced daily treatment regimen, child friendly ‘flavored’ tablets; electronic treatment monitoring system, universal drug sensitivity testing, new drugs and regimen for treating drug resistant patients and active case finding to reach the unreached, which are "excellent steps" for better diagnosis and treatment for all TB patients, Bekedeam added.

Only a fraction of TB cases in the private sector registered with the government

In 2016, about 63% of estimated TB cases in India were registered (called notifications to the government in medical parlance). The government is still not aware of a quarter of TB cases, which might be treated in the private sector or not treated at all, which makes a prevalence survey necessary to understand the real burden of TB in India.

The private sector in India could have treated anything between 1.19 and 5.24 million cases in 2014 (best estimate: 2.2 million cases a year), according to a 2016 study published in the Lancet, based on data from the sale of drugs containing rifampicin.

Ten countries accounted for 76% of the total gap between TB incidence and reported cases. The top three were India (25%), Indonesia (16%) and Nigeria (8%), the WHO report said.

Still, India has come a long way after the government made it mandatory to report every TB case. “Most of the global increase in notifications of new TB cases since 2013 comes from a 37% increase in notifications in India” between 2013 and 2016, the WHO report said.

Low rate of treatment success could fuel drug resistance

A reduction in the total number of cases in 2016 represents some success in India’s fight against TB but the increase in drug-resistant cases suggests a growing threat to control the TB epidemic.

TB is a treatable air-borne infectious disease caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Untreated or partially treated TB patients may infect others, at least partially nullifying India’s attempts to beat back the disease. Partially-treated TB could also result in drug-resistant TB. People with untreated drug-resistant TB could spread the disease to others.

In 2016, 12% of those with drug-resistant TB were those who had been previously treated, while 2.8% were new cases, the WHO report said.

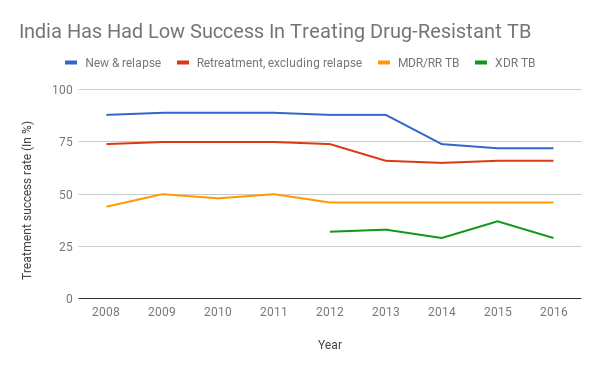

Only 72% of new and previously treated cases of TB registered for treatment in 2015 that should have completed treatment by 2016 did so. If only previously treated cases were considered, the success rate of treatment was even lower--66%. These numbers might not present an accurate picture of treatment success as more than 10% of cases in India were not evaluated, the WHO report said.

Further, treatment completion as measured in India does not mean that the patient is TB-free. The Standards for TB Care in India recommend that patients should be examined after six and 12 months of treatment completion, but India’s national tuberculosis programme does not provide information on the status of all patients after one year. For instance, for several categories of patients--such as those that had extra-pulmonary TB or TB that came back negative when tested microbiologically--the national TB control programme reported how many patients completed treatment, but not how many were cured, as IndiaSpend reported in November 2016.

Of 2.7 million estimated cases of TB in India in 2013, only 39% completed treatment in the national TB control programme, without relapsing after a year of completing treatment, estimated a 2016 study published in the United States and United Kingdom-based health journal Plos Medicine.

Source: World Health Organization

India has also had low success in enrolling patients for drug-resistant TB treatment, with 75% of estimated drug-resistant TB patients not reported to the government as being treated. Of the approximately 147,000 drug-resistant TB patients, 32,914 patients were put on treatment for rifampicin-resistant TB or multi-drug resistant TB--resistant to two of the main anti-TB drugs--while 2,475 started treatment for XDR-TB, resistant to at least four of the core anti-TB drugs.

The treatment success of drug-resistant TB patients in India is low--46% of MDR-TB patients and 29% of XDR-TB patients who began treatment in 2016 were successfully treated, the WHO report said.

India and China accounted for 39% of the global gap in incidence and treatment enrolment for drug-resistant TB, according to the WHO report.

“It is important to first diagnose patients with drug resistance using new, cost-effective diagnostic tools, enroll them for treatment, ensure they complete treatment through individualised attention in managing side effects of drugs and counselling, and check that they are cured,” Swaminathan said.

Further, there should be active TB case-finding rather than waiting for a patient to come to a doctor. But still, “we are not doing well in tracing contacts of existing TB patients, especially children, which helps prevent future TB cases”, Swaminathan said. Only 1.5% of children under five years in households with confirmed TB cases were on preventive medicines, according to the WHO TB report.

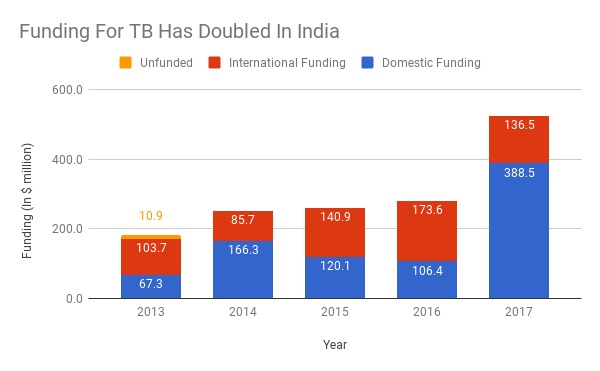

More domestic funding for TB, but $155 million/year shortfall to achieve TB control goals

Funding for TB prevention and care in India doubled between 2015 and 2016, “following political commitment from the Prime Minister to the goal of ending TB by 2025”, the report said. Domestic funding makes up 74% of the $525 million TB budget in India, while 26% is from international sources, the report said.

“The substantial increase in funding is a positive sign. Now we should make sure that the enhanced funding continues,” said Swaminathan, adding that there should be more funding for research and development in TB for new drugs, better and shorter drug regimens, and vaccines which will ensure that TB is eliminated in the future.

Funding should also support programmes such as nutritional and social support for TB patients, she said.

World Health Organization reports in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017.

Still, India would need to spend at least $3.4 billion over the next five years--about $680 million each year--to have a substantial impact on TB, the report added.

Update: This story has been updated to reflect a statement to IndiaSpend from the World Health Organization.

(Shah is a writer/editor, and Yadavar is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.