National Education Policy 2020: ‘Instruction Should Be In The Language Of The Playground’

Mumbai: The National Education Policy is out, and it covers the entire gamut of education. In the context of school education, it proposes linking anganwadis with primary schools, achieving universal foundational literacy and numeracy by 2025, and much more. What does all this mean? What is new? How will it get implemented and rolled out? What could be the timelines? And what could fundamentally change in the lives of young children?

We speak with Rukmini Banerji, chief executive officer, Pratham, one of India’s largest NGOs focused on improving the quality of education in the country. Pratham also runs the Annual State of Education Report (ASER) on learning outcomes.

Edited excerpts:

How are you reading this new policy? What, to you, are the most significant takeaways?

We have been waiting for this since the Kasturirangan Committee handed in their report, and so I am very happy that it is out, because then it is possible--especially given the year that we have right now--to really think about how to implement it. Normally, any system--particularly the education system--is on a treadmill, and you have to drive forward as you are building the road, almost. But now, I feel, with the pace of what will happen this year [given the lockdowns], it gives us some time to think about how to implement this.

After 15 years of doing ASER, where we have been saying that foundational reading and arithmetic is really important, we are of course very pleased with the seriousness with which this foundation has been placed right at the centre of the school education piece. While everybody agrees that these are important things, [it has been given] a very serious, central spot, perhaps that has not been given in our previous education policies.

I think there are two parts to it: One is that these are goals that need to be achieved by a certain stage, and special efforts need to be made. I think the very thick report that came out last year said (in fact in bold letters) that if you do not achieve this, the rest of the policy is irrelevant. And I think some of that is there in this document as well.

But secondly, the importance given to the continuum of early years, I think, is something that we need to absolutely build on. It is not going to be straightforward to do, because it cuts across several ministries and different departments. But that is absolutely the need of the day, and hopefully between departments and other things, we can figure out how that can be done.

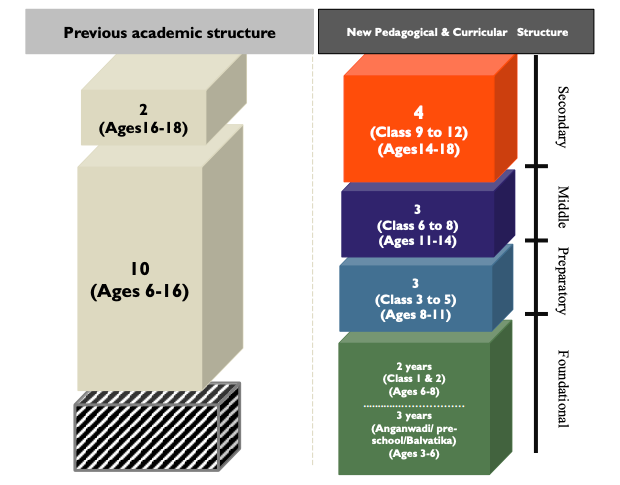

The National Education Policy 2020 proposes a 5+3+3+4 system of schooling, which includes a “foundation” phase for “Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) from age 3”, aimed at “promoting better overall learning, development, and well-being” and ensuring early childhood continuum.

Source: National Education Policy 2020

One is the shift to the 5+3+3+4 system of school education. Is that a reflection of the new thought process, and is that a good thing?

Absolutely. I think that before you come into the grade I, and particularly for children who are coming from families where there may not be a lot of exposure to preschool education, having a couple of years to get ready--in the right way--is absolutely fundamental.

Private schools have had lower and upper kindergarten (KG) before. But I think what this policy, hopefully, will do is to say that you need age-appropriate ways of getting children ready. That will then get you ready for first grade. It is not--as often happens--that you take the schooling that is above and kind of bring it down lower, but rather that you build from what children at age three or four need and take that higher. I think that is the intent of the policy.

In the US, they used to have a programme--I think they still do--called Head Start. So if you do the start well, you have a much greater possibility of leaping forward. I think much of what the document says is reflecting that kind of orientation.

Is it also to do with the fact that 90% of brain growth happens before the age of five?

Happens early, yes. And I think also a lot of your habits for learning are built very early. So if your habit for learning is rote-learning at age lower KG, that in fact goes against all the things that you are going to need when you grow up. Do you feel this structure addresses that somewhat?

I think that while we have had anganwadis [and] private schools have had lower and upper KG, we have been seeing [that there are problems]. At Pratham, we work with several state governments to bring a pre-primary class into the primary school system. Both Punjab and Himachal Pradesh have implemented a pre-primary section in their schools. Punjab has done it in all their schools; Himachal Pradesh in a third of their schools.

But there has been a real struggle as to where the anganwadi leaves off, where the pre-primary begins and who is responsible for that. So by bringing in the importance of this continuum from age three, it will help to sort out some of these problems. Because [even] as states were interested in doing this, there was not a clear guidance that this is the way to proceed, and convergence is absolutely necessary.

Another point is more architectural: the school complex--a cluster of junior schools including anganwadis in a 5-10km radius of a higher secondary school. Tell us about the thinking behind this and what it can do.

Our states vary a lot in the way the linkages between the different levels of schools exist. For example, Delhi has a very different system from many parts of India. In Delhi, children go to municipal schools till grade V, and then you shift into the Delhi government schools which go from grades VI to XII. So there is one shift that you do at the end of primary into your upper primary, but once you are in sixth, you can go all the way.

So, I think there is something to be said for a continuity--in the US, they call it K [kindergarten] through 12, or at least [grade] I to XII. Large parts of the elite private school systems are also built like that, where there is no discontinuity in your growth path. But [in] a bulk of government schools, there is a switch at some time, or sometimes there are two switches.

The way our rural system is constructed is that there is a set of primary schools that feed into upper primary, and there is a set of upper primary [schools] that feed into a high school. I think, in trying to think about how you minimise transition--transitions are points where you lose children sometimes--thinking about the geographical spread and the connections between the schools is important.

In the latest version of the document, I have to read exactly what they mean by school complexes. But to me, a policy document is kind of like an umbrella; it is providing broad guidance. And now it is up to states and other authorities to effectively use the direction and the guidance that is given, to do what makes good sense in that context.

You run the ASER and you look at outcomes. And all your studies continue to point out that the outcomes are weak, learning levels are low, children are not absorbing enough and cognitive skills are low. One of the things that this report seems to be doing is focusing on cognitive skills. So in the context of the work that you have been doing specifically, and the gaps you have been highlighting, what does this report do--directionally, at least?

ASER measures really the basic ability to read, [and] read fluently. The ceiling of the ASER reading test is actually a grade II-level text--the kinds of stories you see in grade II books. And we feel that is at least a level the kids should reach by the end of grade III. The policy actually says that, and we are happy to see that.

But what we also need to address, as the ASER report points out, [is that] there are a lot of kids who are in school, who are in higher grades, who have not reached that level. So I am hoping that the National Mission on Foundational Literacy and Numeracy will definitely help build the foundations, but will also give a lot of focus to the catch-up, because these are not hard things to do. We have done this on a very large scale with state governments and independently; that [in] anything between 30-50 days, a child who is in third, fourth, fifth, sixth can easily pick up this reading and math ability, if time and effort are made during school hours.

So in addition to having a strong beginning, I am really hoping that the policy will push states to say, “let us do the catch-up”. That way, the kids who are already beyond grade III will have a fighting chance to benefit from whatever schooling is going to offer. So I think that these two pieces need to go together.

When you look at this policy, who is it primarily targeting? Is it targeting government schools or private schools, or children who are disadvantaged or less advantaged?

Often people have a sense that these learning deficits are in rural and remote schools. That is not the case. ASER is nationally representative. Yes, it is a rural survey, but it covers 600 districts of India. And for 15 years, a nationally representative sample of children that come from all kinds of school--government schools, private, aided schools. You are saying that 50% of the children are reaching grade V without this ability to read basic text; that 50% cannot be some margin.

[Government] and private schools, especially private schools that are in lower income areas, also suffer from the same sets of issues. So I think this is a policy for India. The elite schools have educated parents, they have a lot of resources, but the bulk of India absolutely needs this.

Home language as a medium of instruction upto grade V while encouraging multiple languages: How do you interpret that?

I think the wording is very important. If I remember correctly, what they are saying is home language, mother tongue, regional language [should be the medium of instruction]. In the last round, when there was a lot of debate over this language, it suddenly became like an English-versus-Hindi-versus-regional language [debate]. What the government should interpret this as is for the younger age groups, the closer the school language is to the language that the child is familiar with, I think that is what will build a strong basis for moving ahead.

[Editor’s note: The National Education Policy 2020 proposes that wherever possible, “the medium of instruction until at least Grade 5, but preferably till Grade 8 and beyond, will be the home language/mother tongue/local language/regional language”.

I am from Bihar myself, and nobody speaks Hindi at home; you speak Bhojpuri, Mythili and when a child first comes to school, you are faced--at least in your textbooks--with Hindi, which you may not understand. So the fact that you have children coming with a home language, which may be the local language, which is a little bit different from the medium of instruction in the school, I think this is our opportunity in India to take this whole business of language and learning really seriously, and not get diverted about whether this is about English or whatever else. And I think that there is mention in the document about bi-lingual [approach]. And I am hoping that bilingual does not mean English-versus-Hindi. It means Bhojpuri-versus-Hindi, or Mythili versus-Hindi.

The old-fashioned teachers in our schools--that common people call Masterji or whatever--are from that local area and therefore that transition in some ways was natural. But now you have teachers who are coming in through more sort of professional recruitment policies and being placed in places across the state. I think we should couch this debate as, the teacher needs to speak the language of the child, so that the child can learn the language of the teacher over a period of time. And this may vary from context, and the three-language formula should allow real contextual connections to be made in this context. Lots and lots of work will need to be done. But if that is the intent--bring the home close to the school, bring the school close to the home--then I think for small children you can achieve quite a lot.

In Delhi or Mumbai, for instance, we all come from different places and speak different languages at home versus what is spoken in the state or the city and then in the school. Is there a logistical problem you see, or is that something we can manage?

For example, for as long as I can remember, the Mumbai municipal schools run in eight languages. While they do not run in 20 languages of India, they run in eight languages. And the biggest number of the schools are in Marathi, Hindi, Urdu and then some Gujarati. Now in these schools, often in crowded areas of Mumbai, different floors of the same building have different language schools. But the children are playing together in the playground in the same way. I almost feel like we should teach in the language of the playground, because that is where real communication is happening. So Mumbai has shown that these things can be done. You have to figure out how to do them.

In Delhi, for example, you may not need eight languages because maybe a bulk of the population that is in Delhi speaks certain [languages]. I think this is also an opportunity for private schools, who may have more resources--[including] in terms of parental resources, of parents who may know many languages--to really think about how you can provide [education] in the languages that make sense in your context.

What is your sense on when a good part of the report could be potentially implemented, or when would you like to see things implemented?

Let me say a couple of very practical things. One is, there is a large number of schools in India (varies from state to state) on the early childhood side where there is already an anganwadi in the school compound. There is a physical presence already, and there you need to ensure that the developmentally appropriate activities happen in the anganwadis and those children move into the school. I do not think that is such a big step; it is two departments coming together.

I have seen in many schools in Punjab, where the actual convergence on the ground is quite smooth. But on top, the buildings may be different. I think that is one [thing] that can be [implemented] relatively quickly if the two departments work out what would be the logistics, because the kids are physically already there in the same space, the teachers are physically already there. How do you increase the capability of teachers? That may take a little longer, but I do not think that should stop you from doing things in this continuum.

On the catch-up side, with kids who are in grades III-VI who are still lacking foundational skills, my own wish is, the minute school opens in this very strange year, we should do a very quick ASER-like assessment, which takes five minutes, to figure out where the child is at. And if we find that the child is not able to read or do basic arithmetic, do a quick campaign--these campaigns can be done by the schools themselves--to help them reach [the appropriate] level. So I would really like the catch-up to happen [as soon as] the schools reopen, and start thinking about how we will bring our early childhood continuum together. It may be a little bit more difficult where physically kids are not together, but where they are, very practical things can be done to start quickly.

There are lots of other things that will take time--how this bilingual stuff will happen, what the textbooks will be like, the school complex one, I have to really understand what that means. I think foundational learning, early childhood continuum and the catch-up--make it a national priority, move behind it. Do not get stuck by what I feel is an over-ambitious curriculum, which often has been an obstacle in getting some of these simple things done.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.