‘The People Of Uttarakhand & Himachal Want Roads, Not Landslides’

Inadequate geological investigations, very sharp slopes going up to 60-70 degrees, roads being too wide, roads right by the riverside, deforestation are increasing disasters in India’s Himalayan states, says environmentalist Ravi Chopra

Mumbai: This year, the onset of monsoon in India was under unusual circumstances. The country saw its highest ever rainfall in the month of May. The official onset of monsoon was declared over the hill states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand around June 20 and monsoon covered the entire country by June 29. Right from the start, rains wreaked havoc in Himachal Pradesh. By July 17, the state had recorded more than 100 deaths and losses worth more than Rs 800 crore due to heavy rainfall and landslides. Many districts including Mandi, Kullu and Shimla were affected.

On August 5, a disaster in Uttarakhand’s Uttarkashi area led to widespread destruction. A first landslide or mudslide occurred in Dharali village, followed by another in Harsil, about 6 km away. Videos showed many structures along a riverbed being washed away by a river of debris that came crashing down a hill in Dharali and a similar flood in an army camp in Harsil. While initially reports claimed the cause to be a cloudburst, experts have pointed out that the reason could be a glacier breach or avalanche as well.

India is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change which makes our annual monsoon more erratic. Climate change is expected to increase the frequency of extreme weather events like heavy rainfall and Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOFs). Coupled with poor planning, inadequate mitigation measures and disaster preparedness, unplanned urbanisation and deforestation, it is leading to never-seen-before disasters in India’s Himalayan states of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh.

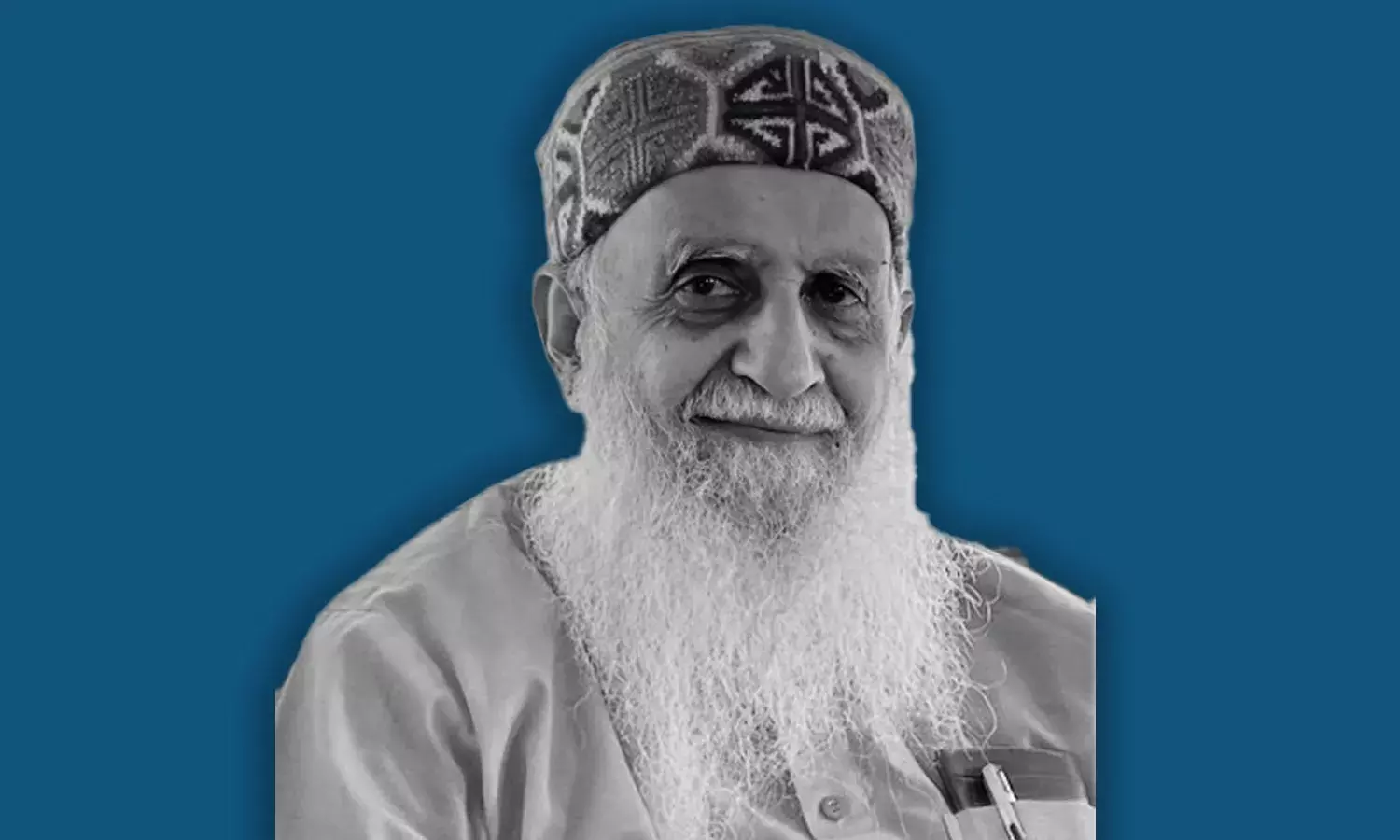

Ravi Chopra is a respected environmentalist working on the Himalayas in India. He has been advocating conservation, better planning of infrastructure projects, and community participation in the hill states for about 40 years now. An engineer by profession, he was also the director of the People’s Science Institute, a nonprofit public interest research organisation that serves the needs of rural populations.

In 2019, Chopra was appointed as chairperson of a “high-powered committee” created by the Supreme Court to review the Char Dham project, which aims to provide year-round accessibility to Uttarakhand’s four major Hindu pilgrimage sites: Kedarnath, Badrinath, Yamunotri and Gangotri. Chopra had resigned three years later from the committee, stating that his belief that the panel could protect the fragile ecology of the Himalayas “has been shattered”.

The ecological concerns he had been voicing for years were proven correct when the Silkyara tunnel, part of the Char Dham project, collapsed in 2023 endangering the lives of 40 labourers trapped inside.

In an interview with IndiaSpend conducted before and after the Dharali disaster, Chopra spoke extensively on the increasing disasters in these hill states, how the government disregarded its own notes of caution, how people don’t want foolhardy development and why tourism needs to be regulated.

Edited excerpts:

In the case of the disaster in Uttarakhand’s Dharali on August 5, the videos show that the structures that got affected were constructed very close to the river. While this is a rural area, someone must have given permission?

Yes. The village of Dharali is higher up and far from this location. The national highway passes from near the riverbank. Those were the hotels, homestays, lodges that were built around the road so that these are easily accessible. Unfortunately, they were also lying at the tail-end of the debris of older avalanches. It is most likely that the material [soil] is not consolidated, it is loose material that can be washed away in a flood. Whoever gave permission to construct here ought to be held accountable.

Both Himalayan states of Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand are seeing floods since the onset of monsoon. The number of landslides and land subsidence is also increasing. The Himalayas are a young range, but are there factors beyond the geographical and geological for these increasing disasters? In your observation, what is making this kind of destruction common every monsoon?

Both these states are part of the central western Himalayan range. These ranges are geologically young. The oldest range of the Himalayas is about a maximum of 60 million years old. They look like big mighty mountains, but when you get close, you can see that they are disjointed, fractured ranges and they have fissures in them. Any attempt to disturb the stable slopes has to be done extremely carefully.

In the last five to eight years, there has been a big push by the government of India to build infrastructure in these regions. Back in 2012, the government of India announced a new national highways policy in which it was mandated that all the national highways would be two-lane or 10 metres wide and will have a blacktop surface. What that means is that the road is actually about 13 metres wide because they have to cut 1.5 metres for having crash barriers on either side.

Now, there is a general rule that one should not cut slopes that have an incline of more than 30 degrees. But the National Highway Authority of India and its contractors have been ignoring this. Back in March 2018, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways put out a notification which clearly said that the experience of the previous years had shown that it is not easy to build wide roads in the mountain regions. That there had been a lot of deforestation, that there had been landslides and a lot of damage. All this was known, research was done, this was a notification that was developed as a result. But then in the zeal to develop these roads and particularly take large numbers of pilgrims in Uttarakhand to the four shrines, the Char Dham, they simply ignored such norms and constraints. This notification was never revealed either to the courts or even when the high-powered committee on Char Dham Pariyojana was set up, of which I was the chairperson. They did not adhere to it and later they changed that notification.

Second, if you are going to build such wide roads, then you have to undertake very good prior geological investigations. When our high-powered committee toured this area, we found that the geological investigations were inadequate and we saw lots of evidence of slopes on the verge of sliding or landslides having taken place. The protection walls are inadequate and sometimes poorly built.

In the case of Himachal, there's another disaster. In Himachal, they have built roads along the rivers. Before Independence, roads were never built in the valleys in both Himachal and Uttarakhand but rather built on the top. When there is a flood in the river, the erosive force of the flood water is so high that it sweeps away the man-made roads and other structures [downstream, in the valley].

So, these are the primary causes: inadequate geological investigations, very sharp slopes going up to 60-70 degrees, the roads being too wide and roads right by the riverside. Besides, there is a lot of deforestation that takes place and effectively, many of these slopes are left unprotected.

Even in the case of Dharali, you wrote that this was a warning ignored. What made you say that?

Yes, it is a warning unheard. I have written about various reports that have been ignored in the past. In this specific case, when we went to the region during the HPC’s fieldwork, geologist Dr Navin Juyal pointed out these hanging glaciers at the time and said that this area is subject to repeated avalanches and that the slope itself is made of debris of past avalanches. Therefore, this is not a very stable area.

Also, you should not be widening roads by cutting deodar trees that minimise damage to slopes. And yet, the government is planning to widen the national highway to Gangotri by 10 feet by cutting 6,000 trees.

On August 5, the incident happened around 1.30 p.m. People on their way up to Gangotri or those descending often stop at Dharali for lunch. I was told that other than tourists, there were a lot of labourers from Bihar working there and from Nepal also, who had come for apple picking. These people will never get accounted for. Therefore, I think the number of dead is actually much higher than what we know, probably 100 or 200.

Many districts of Himachal and Uttarakhand are landslide prone. Even then, is landslide zonation and mapping poor? Are landslides and land subsidence happening in new spots and authorities getting caught off guard?

There is an atlas called Landslide Hazard Zonation Mapping in the Himalayas of Uttaranchal and Himachal Pradesh using remote sensing and GIS techniques. This atlas has been put out by the National Remote Sensing Agency in 2001. Mapping is not poor. The research is done. The data, the maps are put out and nobody looks at them. It lies on the shelves of the decision makers.

You spoke about roads being too wide or being constructed right next to the riverside. But both these states have an increasing population and therefore development needs. Are these states failing to balance their development needs with the geological reality, which is that rainfall is increasing and landslides are increasing?

My grandmother used to say, if you follow the laws of nature, you will have a happy life. These people are not willing to respect the existing natural conditions. They know that slopes that are steeper than 30 degrees should not be cut. This is stated by their own engineers and researchers. So, if you are going to ignore the constraints of nature, you are simply inviting disaster. The people of neither state want foolhardy development. They want sustainable development. They want roads, they don't want landslides.

Data show that both the states have seen new roads and bridges worth thousands of kilometres being laid or under construction in recent years. What impact does the use of asphalt and concrete have on the percolation of rainwater in the ground? Does that erode slopes?

The kind of geological investigations that are required are not done because roadwork contractors, engineers and the government have to meet a targeted date. Very often, the targeted date is determined by the next election and so they are in a rush to show the public, look we are doing such great things for you.

The people of Joshimath had been complaining of cracks in their homes for a while before the actual subsidence happened. Are you seeing anger on the ground because you have lived in this region for so long? What is the sense among the people?

If you ask me, there is a whole class of people who are benefitting from this kind of development. These include middle class, upper middle class and wealthy people. They are thrilled that, you know, I can go to Badrinath and come back in three days at most. Our local Uttarakhand and Himachal middle class also feels quite happy that our state is progressing, that the economy of the state is growing. But even these people, when their house collapses, then they come to their senses. The real situation is that in Uttarakhand people are disheartened. They have been witnessing disasters since 2013. Disasters in Himachal Pradesh are more recent.

The slopes are sliding in several places. When we travel in the mountains, the trees are not standing straight up. They’re at an angle to the slope because that slope has slid earlier. In technical language, this is known as a ‘creep’. So the slope is creeping gradually. This is the first sign that this slope is in trouble. Now you have to be very careful here. But a developer gets permission to put up a building or something here. They just go cut the forest, cut the slope, make the space, put up the structures and invite disaster.

After the Indo-China border war, the government rightly decided that we needed to build motorable roads in this area that could take troops and military equipment right up to the Indo-China border. So they built a road and that’s when the local administration noticed that there were fissures in the ground in Joshimath. This was as far back as 1976. The UP government of that time appointed a committee. They proposed a number of measures to prevent further damage. So, the report comes out in 1976, no action was ever taken. Not a single one of these recommendations was ever adopted. Nobody rejected them, but the government did not do anything either.

The pressures of development are also leading to large scale deforestation in both the states.

Massive deforestation is being done and this is in an era of climate change. The whole world is screaming that we need more trees. Even our own politicians, these people with forked tongues, they all talk about planting more trees…. But we end up with deforested, massively denuded areas at a time when we desperately need more trees to absorb all that carbon dioxide that we keep increasing.

Do you think that tourism should be regulated in these two states now? Recently there was a regulation on the number of tourists that can enter Mussoorie.

Tourism was always regulated in the mountain areas. It's only in recent years that we have abandoned the regulations. The forest department had put in restrictions on the number of people and ponies that could go to the stretch from Gangotri to Gaumukh, which is about 19 km, after many tourists started going there 20 years ago. I remember you could not take a car inside the Mall Road of Mussoorie in the 1990s. We’ve had these rules. This government is an anti-environment, anti-people government. It does not respect any rules of nature, it does not respect human life, forget about wildlife.

In Uttarakhand and Himachal both, there are thousands of spots where people can come and enjoy nature. But that enjoyment will only last as long as nature remains pristine. If you destroy nature, then people will stop coming. So, you are killing the golden goose. And access to unexplored areas must be extremely tightly regulated.

When the government broke down the Char Dham project into individual road packages or contracts to bypass having to do an environment impact assessment, do you think that set the precedent for the rest of the country?

In this case, the government was openly perpetrating a fraud. It was a fraudulent exercise. The environmentalists showed the court that if we put these 53 projects together, it adds up to the entire Char Dham project of 900 kilometres. And yet, the court did not come down on this kind of fraud. So, I blame the courts also for being cowards.

In 2023, the Supreme Court had said that it was going to form a high profile committee to assess the carrying capacity of Himalayan states. This was in reference to overcrowding because of tourism in all 13 Himalayan states, but nothing seems to have moved after that. Similarly, NGT had formed a committee to check if higher Himalayas can be declared an eco-sensitive zone but the committee deferred the same. Were both these lost opportunities?

The courts can only issue orders. Who's going to execute them? It's the executive that has to execute any order or any law framed by the court. The executive is reluctant to do these things. The money lobby, the contractor lobby, are just too strong. And the best example I can give you is the Madhav Gadgil committee that was formed for determining the carrying capacity of the Western Ghats. They came out with a fantastic report. And what did the government do? They formed another committee to review it. Then the state governments of Kerala, Karnataka and Goa started objecting to it. The money lobbies are just too powerful. People's movements don't happen overnight.

I led another Supreme Court nominated committee in 2013. We reviewed the impact of hydropower projects in Uttarakhand and we supported the view of the National River Ganga Basin Authority. It said that the stretch from Uttarkashi up to Gangotri should be declared as an eco-sensitive zone and a no-go area for large development projects. The Congress government of that time proceeded to cancel the construction of three dams, one of which was already under construction. They gave NTPC Rs 600 crore as compensation. That's the kind of approach we need to take.

(Priya Verma, intern with IndiaSpend, contributed to this report)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.