Indian Subcontinent Will Face Deadly Heat+Humidity By Century’s End

A man wipes his face on a hot summer day in the old quarters of Delhi in June 2015. If humans continue to emit greenhouse gases at current rates, in many parts of South Asia weather conditions are likely to become intolerable for humans, particularly during extreme years.

High humidity levels coinciding with high temperatures are likely to create lethal weather conditions and imperil the lives of millions across large parts of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh by the end of the century, according to new research published in the scientific journal Science Advances. Climate change will make such conditions more frequent as the 21st century comes to a close, the study said.

Yet, the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) does not take humidity into account in characterising heat waves, even though temperatures that fall below IMD’s definition of a heat wave, when combined with a high humidity level, can imperil human lives. This shines the light on an area ripe for policy action.

Wet bulb temperature, the new metric

“There are certain temperature and humidity conditions under which no human can survive,” Jeremy Pal of Loyola Marymount University in the US, a co-author of the study, said in an email to IndiaSpend.

The key metric here is wet bulb temperature (WBT)--a combined measure of temperature and humidity--that quantifies the discomfort the human body feels, as opposed to dry bulb temperature (DBT), a measure of air temperature alone that official weather services announce.

WBT can be high even when the temperature is relatively low. For instance, if the temperature is 30°C (degrees Celsius) and relative humidity 90%, the wet bulb temperature amounts to a very uncomfortable 29°C, as per this calculator. The US National Weather Service considers WBT above 30°C extremely dangerous.

Our survival depends on our bodies staying at a consistent temperature. Normally, our core temperature--from the top of the head to mid-chest, encompassing the brain, lungs and chest--is regulated at 37°C, and our skin at 35°C. Sweating helps us shed excess heat--sweat beads cool the skin, and evaporation of sweat gets rid of heat, restoring the equilibrium.

This process of thermoregulation occurs efficiently only when ambient air is favourable for us. Air can hold a limited quantity of water until it saturates. In dry air without much water content, your sweat evaporates quickly, causing cooling. In humid air that has much moisture already, sweat does not evaporate as easily, leading to overheating of the body.

WBT is “the temperature that air would cool to if water were evaporated into it until saturation”, Pal explained. In other words, it is the temperature that air cools to beyond which it cannot take any more water.

WBT is similar to the heat index, also called the apparent temperature, and refers to how hot it actually feels.

“Wet clothes hanging on a line will dry much faster in warm dry air than warm humid air. This is the same for the human body. If the air is warm and dry, the body can perspire and cool more efficiently compared to if it is warm and humid. This is why the same temperature feels much warmer when it is humid compared to dry,” Pal said.

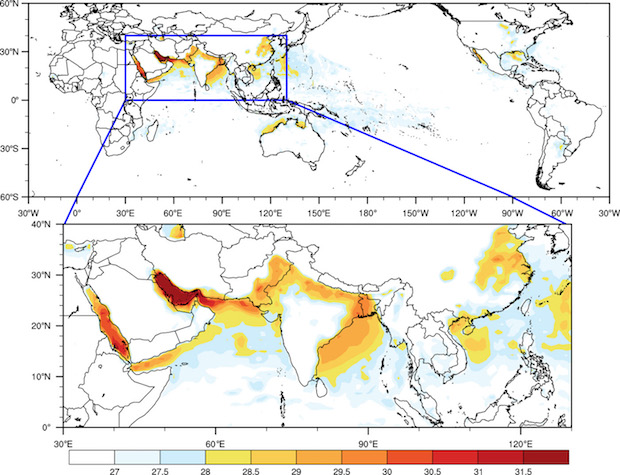

Spatial Distribution Of Highest Daily MaximumWet-Bulb Temperature, 1979-2015

The distribution of the maximum six-hour wet-bulb temperature ever recorded, according to observations in modern record (1979-2015).Source: Science Advances

Climate change will cause high WBT

If the WBT exceeds the human body’s skin temperature of 35°C (which is 2°C below the body’s core temperature), perspiration can no longer act as a cooling mechanism and the body will quickly overheat, resulting in death, Pal said. That 35°C is the upper limit of human survivability.

“If wet bulb temperature exceeded 35°C for more than six hours, no human will be able to survive no matter how physically fit. This means the entire exposed population is vulnerable, not just the weak,” Pal said.

“[T]he densely populated agricultural regions of the Ganges and Indus river basins” are “identified as the most at risk for heat waves caused by climate change, due to overlap of intense hazard and acute vulnerability”, Elfatih Eltahir, hydrology and climate expert from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US, another co-author of the study, told IndiaSpend in an email.

This region is home to more than 1 billion people, most of whom are small and marginal farmers, farm workers, construction labourers and migrant labourers who work outdoors and have no access to air conditioning, the study pointed out.

If humans continue to emit greenhouse gases at current rates, in many locations the outdoor conditions and indoor locations without air conditioning are likely to become intolerable to humans during extreme years.

The 2015 heatwave saw high WBT

WBT need not rise to 35°C to cause death, and so far the region has not reached that upper limit. However, in the 2015 heat wave across India, Pakistan and Iran, WBTs seemed to be creeping up to 35°C.

Anything above 30°C can kill a lot of people, the study noted.

In India, May 2015 saw temperatures soaring above 40°C, spiking as high as 47.2°C and killing at least 2,300 people, most of them in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Odisha too was affected. For people living on coasts, humid air made high temperatures unbearable, resulting in deaths among the weak, elderly, poor and very young.

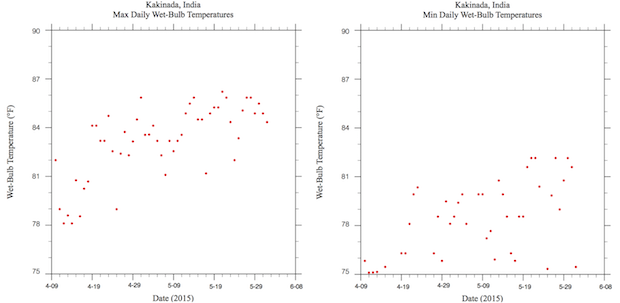

For example, in Kakinada in Andhra Pradesh, the highest wet-bulb temperatures peaked around 30°C during the 2015 heat wave.

Maximum & Minimum Daily Wet-Bulb Temperatures, Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh

The plots show the daily maximum and minimum wet-bulb temperatures (WBTs) for Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh, in 2015. The highest WBTs of the latest heat wave have peaked around 86°F (30°C). There are days when the WBT did not fall below 82°F (27.777°C).Source: Robert Kopp, Rutgers University

Scientists who studied India’s 2015 heatwave concluded that the region was likely to see intense heatwaves once in every 10 years instead of once in every 100 years, IndiaSpend reported on June 21, 2017.

What lies ahead

The present paper is an extension of a study focussed on Southwest Asia that Eltahir and Pal published in 2016 in the scientific journal Nature Climate Change.

These studies were motivated by a 2010 study published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) that first projected that extreme temperature and humidity--that is, wet-bulb temperature--which presently never exceeds 31°C, “would begin to occur with global-mean warming of about 7°C, calling the habitability of some regions into question”.

At 11-12°C warming, such regions would spread to encompass the majority of the human population as currently distributed, the study said, adding that heat stress could help explain trends in the mammalian fossil record.

Zooming in on South Asia using a high-resolution climate model to make the best currently-feasible projections of climate change extremes, the authors of the present study examined two possible scenarios: The ‘let’s-fiddle-while-Rome-burns’ scenario, and the ‘let’s-be-seen-to-be-doing-something’ scenario (in which measures similar to those under the Paris Climate agreement are taken).

In the first case, WBTs shoot up to and in some cases exceed 35°C “over most of South Asia, including the Ganges river valley, northeastern India, Bangladesh, the eastern coast of India, Chota Nagpur Plateau, northern Sri Lanka, and the Indus valley of Pakistan”, the study said.

In major urban centres such as Lucknow and Patna that have more than 2 million population each, WBTs would reach and exceed the survivability threshold, the study reported.

“The 35°C threshold is likely to occur once every twenty years or so. 30°C, however, would be exceeded on average every other year or so depending on the region,” Pal said, adding that not even the fittest of humans can survive in even well-ventilated shaded conditions under WBT of 35°C or above.

In the latter mitigation scenario, although the temperatures do not reach the upper limit of human survivability of 35°C, lethal conditions could occur above 30°C.

“Low lying areas, monsoon, and irrigation shape the distribution of wet bulb temperature,” Eltahir said, adding that India should adopt a clean energy policy at the national level and push internationally for emissions reductions.

The IMD does not take humidity into account in characterising heat waves. Temperatures that fall below IMD’s definition of a heat wave, when combined with humidity, do get to the upper limit of the WBT for human survivability. Heat-wave deaths have increased three-fold over 23 years, IndiaSpend reported on April 20, 2016.

Clearly, this is an area ripe for policy intervention.

(Varma is a freelance journalist based in Andhra Pradesh. He writes on science, with a special interest in climate science, environment and ecology.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”