India Has The Highest Suicide Rate in South East Asia, But No Prevention Strategy

Mumbai: India had the highest suicide rate in the South-East Asian region in 2016, a new report by the World Health Organization (WHO) has revealed. India’s own official statistics, which map the number and causes of suicides in the country, have not been made public for the last three years, hindering suicide prevention strategies and efforts to implement the WHO's recommendations in this regard.

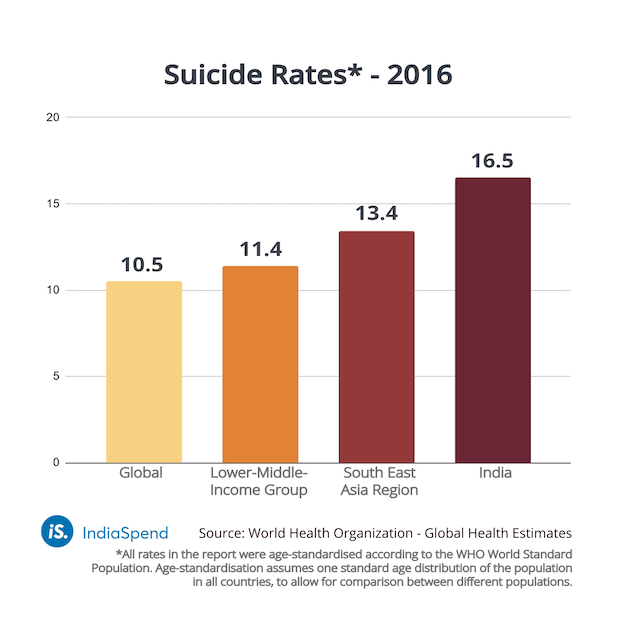

India’s suicide rate stood at 16.5 suicides per 100,000 people in 2016, according to the WHO report. This was higher than the global suicide rate of 10.5.

The report presented suicide rates for countries and regions using data from the WHO Global Health Estimates for 2016. When classified according to region and income, India is part of the South-East Asia region and the Lower Middle-Income group of countries. India’s suicide rate (16.5) was higher than the rate of its geographic region (13.4) and the rate of its income group (11.4).

India also had the highest suicide rate in the South-East Asian region for females (14.5). India’s male suicide rate was not the highest in the region, but at 18.5, was higher than the female rate and the combined suicide rate. India stood third in the region in male suicide rates, after Sri Lanka (23.3) and Thailand (21.4).

WHO recommendations

Despite having a suicide rate higher than the global average, India has not acted on the WHO’s recommendations for suicide prevention. In 2014, the WHO had released a report with a series of recommendations for successful suicide prevention. It proposed following the public health model for suicide prevention, consisting of four steps:

- Surveillance

- Identification of risks and protective factors

- Development & evaluation of interventions

- Implementation

India has not progressed beyond the first step, surveillance, defined in its 2014 report as the systematic collection of data on suicides and suicide attempts.

However, even in this, the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) 49-year-old practice of announcing suicide statistics was stopped abruptly in 2016 (when it released suicide statistics for 2015), and suicide statistics have not been made public ever since.

Farmer suicides

Up to 2016, every year, the NCRB compiled the preceding year’s suicide data in an annual report titled ‘Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India’ (ADSI). These reports presented the total number of suicide deaths in the country, categorised by cause, means, occupation, educational status and economic status.

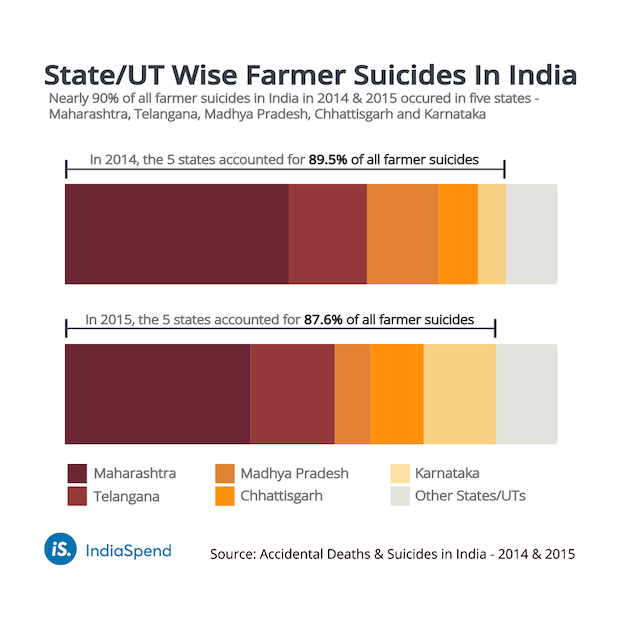

In 2014 and 2015, the NCRB included a chapter with data on suicides within the farming sector. This chapter highlighted that five states (Maharashtra, Telangana, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Karnataka) had accounted for nearly 90% of all farmer suicides in the country in 2014 and 2015.

Two years after the introduction of the new chapter, the NCRB stopped publishing its annual report.

The NCRB had found discrepancies in the data submitted for 2016 and had asked states to re-verify the data, the government told parliament.

Monitoring methods

While the NCRB claims the 2016 ADSI report is being finalised, India’s data collection remains insufficient, when measured against the WHO’s suicide prevention recommendations.

The WHO’s 2014 report had suggested that countries must monitor data from multiple sources such as vital registration data (the number of births and deaths recorded), hospital-based systems and surveys; the NCRB collects suicide data for its ADSI reports from a single source--the police departments of states and union territories.

Claiming to have used years of high-quality vital registration data to prepare its suicide estimates, the WHO’s latest report said India’s death registration data was not usable by WHO standards.

The latest report on global suicide estimates rated the death registration data quality of each country on a scale of five, where one was the highest score and five the lowest. India’s was rated four and termed “unusable or unavailable” due to quality issues.

India also does not compile and publish data on suicide attempts at the national level. The WHO recommended using hospital-based systems and surveys to monitor suicide attempts.

A previous suicide attempt is the single most important risk factor for suicide in the general population, the 2014 WHO report had noted. Failing to track suicide attempts can leave many at risk--the WHO estimates that for every person who dies by suicide, more than 20 others attempt it.

National strategy needed

To lower its suicide rate, India must first collect high-quality data and build a comprehensive suicide surveillance system, as the WHO recommends. A national strategy and action plan, informed by better data, could drive the implementation of the four-step public health model of suicide prevention.

While India has implemented a National Mental Health Programme, it has no national-level response system. A national suicide prevention strategy is required to raise awareness of suicide as a public health issue and prioritise suicide prevention, as Vice President of India, M. Venkaiah Naidu, said in an address to the Indian Association of Private Psychiatry in 2018.

(Ahmed is a graduate of architecture from the University of Kent and is an IndiaSpend contributor.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.