India Continues To Miss Key Health Targets

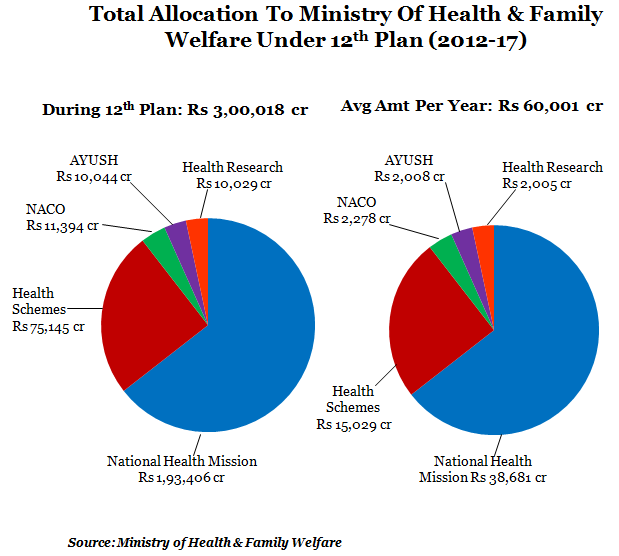

| Highlights *12th Plan allocation for Health Ministry is Rs 300,018 crore or approximately Rs 60,000 crore per year *National Health Mission gets the largest pie; around Rs 38,681 crore every year *12th Plan targets include reducing infant mortality rate to 25 per 1,000 live births and maternal mortality rate to 100 per 1 lakh live births |

Predictably, the NHM gets the largest slice at around Rs 38,681 crore every year while health research, which supports clinical and bio-medical research and training, gets the least. The National Aids Control Organisation (NACO) and the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH) will get around Rs 2,000 crore per year. The other health schemes will get around Rs 15,000 crore per year during the 12thPlan. So what are the objectives of the 12thPlan? Reduce infant mortality rate (IMR) to 25 per 1,000 live births; reduce maternal mortality rate (MMR) to 100 per one lakh live births, reduce total fertility rate (TFR) to 2.1 and raise sex ratio in the 0-6 year age group to 950 per thousand. The question again - will this be possible by 2017? The following data points give an idea of the progress on the indicators over the last five years:

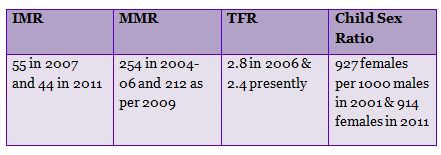

Predictably, the NHM gets the largest slice at around Rs 38,681 crore every year while health research, which supports clinical and bio-medical research and training, gets the least. The National Aids Control Organisation (NACO) and the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH) will get around Rs 2,000 crore per year. The other health schemes will get around Rs 15,000 crore per year during the 12thPlan. So what are the objectives of the 12thPlan? Reduce infant mortality rate (IMR) to 25 per 1,000 live births; reduce maternal mortality rate (MMR) to 100 per one lakh live births, reduce total fertility rate (TFR) to 2.1 and raise sex ratio in the 0-6 year age group to 950 per thousand. The question again - will this be possible by 2017? The following data points give an idea of the progress on the indicators over the last five years:  Right now, there are around 44 deaths per 1,000 live births, which was a decline from 55 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2007. Maternal deaths, per 100,000 live births, have gone down to 212 compared to 254 in 2004-06. The number of girl child per 1,000 boys has gone down to the present level of 914 compared to 927 in 2001. Total fertility rate (TFR), or the average number of children born to a woman in her lifetime, has declined to 2 as compared to 3 five years ago. The following table shows how difficult it is likely to be to achieve the goals of the 12thPlan:

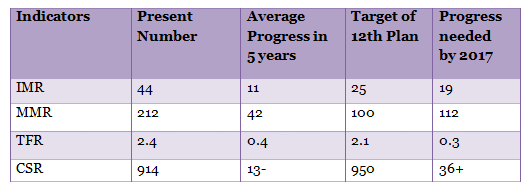

Right now, there are around 44 deaths per 1,000 live births, which was a decline from 55 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2007. Maternal deaths, per 100,000 live births, have gone down to 212 compared to 254 in 2004-06. The number of girl child per 1,000 boys has gone down to the present level of 914 compared to 927 in 2001. Total fertility rate (TFR), or the average number of children born to a woman in her lifetime, has declined to 2 as compared to 3 five years ago. The following table shows how difficult it is likely to be to achieve the goals of the 12thPlan:  The current trend in social indicators suggests that meeting the 12th Plan targets will be a herculean task. Or the pace of progress has to be considerable hereon. If you take a look at the progress to be made, it would appear that only TFR can be achieved by the end of the 12thPlan. Other indicators like IMR, MMR and child sex ratio are likely to be missed again. The reason - India needs to reduce IMR by 4 per year and MMR by 22 and improve the child sex ratio by 7 every year to reach the desired targets by 2017. TFR, which needs to reduce by 0.06 every year, looks like the only saving grace, like we said. The past track record reflects the slow performing speed or probably the high, unachievable targets that are set. However, the last five year plan failed in securing important health targets like MDG. Looking at the trend, even pumping more money may not yield desired results. Data also shows that during the 11th Plan, the release (Rs 93,981 crore) was around 20% lesser than the allocation (Rs 119,364 crore) though the expenditure (Rs 89,576 crore) was 95% of the release. Probably, efficient mechanisms to release funds are a way out, combined with strict implementation and monitoring during the 12thPlan. The allocation for the 12thPlan has been increased by 335% to Rs 300,018 crore as compared to the expenditure of the 11thPlan. But data also shows that increased health expenditure over the years is not translating into achievements of the targets set by the Planning Commission. One idea behind the increase in funding is to reduce poor household’s out-of-pocket expenditure but as we earlier wrote, absence of doctors and lack of facilities force people to avoid public healthcare.

The current trend in social indicators suggests that meeting the 12th Plan targets will be a herculean task. Or the pace of progress has to be considerable hereon. If you take a look at the progress to be made, it would appear that only TFR can be achieved by the end of the 12thPlan. Other indicators like IMR, MMR and child sex ratio are likely to be missed again. The reason - India needs to reduce IMR by 4 per year and MMR by 22 and improve the child sex ratio by 7 every year to reach the desired targets by 2017. TFR, which needs to reduce by 0.06 every year, looks like the only saving grace, like we said. The past track record reflects the slow performing speed or probably the high, unachievable targets that are set. However, the last five year plan failed in securing important health targets like MDG. Looking at the trend, even pumping more money may not yield desired results. Data also shows that during the 11th Plan, the release (Rs 93,981 crore) was around 20% lesser than the allocation (Rs 119,364 crore) though the expenditure (Rs 89,576 crore) was 95% of the release. Probably, efficient mechanisms to release funds are a way out, combined with strict implementation and monitoring during the 12thPlan. The allocation for the 12thPlan has been increased by 335% to Rs 300,018 crore as compared to the expenditure of the 11thPlan. But data also shows that increased health expenditure over the years is not translating into achievements of the targets set by the Planning Commission. One idea behind the increase in funding is to reduce poor household’s out-of-pocket expenditure but as we earlier wrote, absence of doctors and lack of facilities force people to avoid public healthcare.Next Story