In Shadow Of Conflict, Wildlife Trade Has Been Rising In J&K

Jammu: The endangered hangul, or Kashmiri stag, a species of which fewer than 250 now exist in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), is not just the state animal of J&K but a powerful symbol of the dangers faced by distinctive species of animals, and even plants, in a region that is a precious habitat for Himalayan wildlife.

Conservationists with the Noida-based Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) have been documenting and trying to draw attention to growing threats to wildlife that have largely been overlooked amid the conflict in the region and, in particular, to a worrying shift in the motivations for hunting animals.

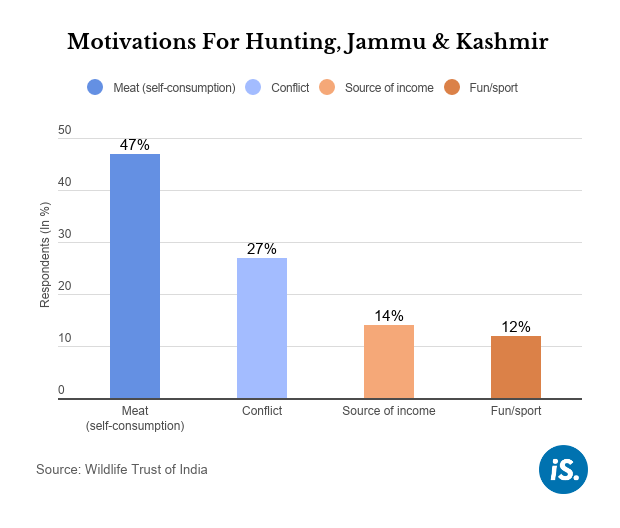

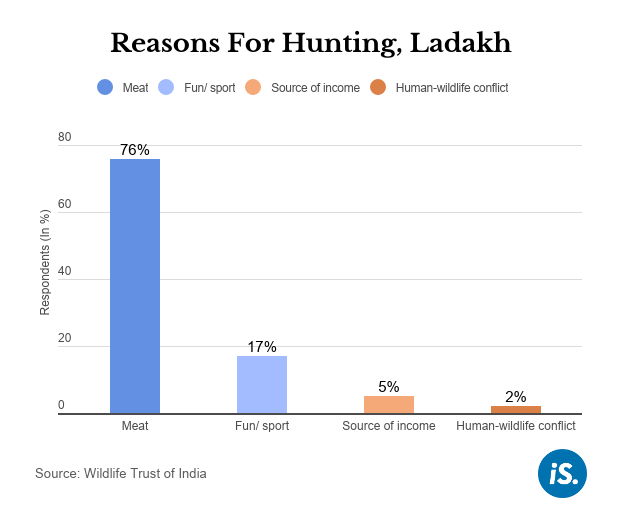

“Earlier, hunting was mainly for self-consumption but now, hunting for trade is gaining popularity,” said Shiekh Marifatul Haq, a researcher at WTI who is conducting a first-of-its-kind study on the state of wildlife in Jammu and Kashmir.

Apart from threatening wildlife conservation, hunting and poaching activities are also alarming because they increase the chances of zoonotic spillovers--the transmission of infections from animals to humans. These spillovers can result in disease outbreaks like COVID-19.

Protected Himalayan wildlife targeted

Species at risk on a global scale such as hanguls, leopards, markhors (large goats with screw-like horns) and the Himalyan musk deer are among those targeted the most for hunting in Jammu and Kashmir, according to the preliminary findings of the WTI study, discussed at a workshop in Jammu in February attended by this reporter. This is a flagrant violation of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 (WPLA), which accords them its highest level of protection, and lays down a punishment of imprisonment for a term of three to seven years and a fine of not less than Rs 10,000.

While the population of the hangul in the early 1900s was about 5,000 and was widely distributed in the mountains of Kashmir and in some parts of Himachal Pradesh, today there are only 237 and their range is largely restricted to the 141 sq km of Dachigam National Park and a few adjoining areas. Globally, the animal is classified as critically endangered.

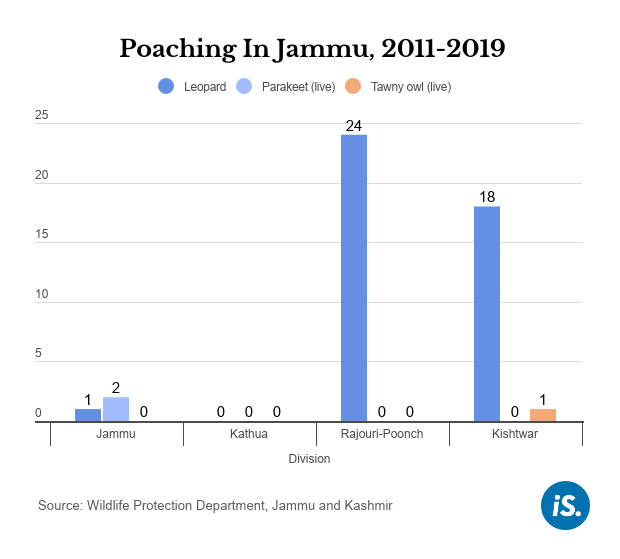

At the Jammu workshop, Amit Sharma, wildlife warden of Jammu, revealed that 43 leopards have been found to have been poached in the last nine years, and the numbers of those killed were likely to be even higher.

Other species targeted by hunters, the ongoing study has revealed, are the Himalayan black bear, grey Himalayan goral, jackals, foxes, barking deer, the Himalayan monal and the porcupine, all of which are protected under the WLPA.

Like hanguls, markhors, the Himalayan musk deer, the Himalayan black bear and the Himalayan monal (a rainbow-coloured bird) are native to the Himalayas. Globally, markhors are classified as “near threatened”, the Himalayan musk deer as “endangered” and the Asiatic black bear, the species to which Himalayan black bears belong, as “vulnerable”.

While leopards are distributed over a wider area than the Himalyan species, and are more adaptable, they too are threatened. India’s leopard population has declined by 75-90% in the last century owing to threats such as habitat loss, depletion of prey population, human-leopard conflict and poaching.

“In some cases, poaching and butchering of an animal can potentially result in contact with bodily fluids of the animal like blood, saliva, urine and faeces either through the oro-nasal [relating to nose and mouth] route or through a cut or other break in the skin,” said Abi T. Vanak, a senior fellow at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), on zoonotic spillovers. Moreover, he said, high levels of stress in trafficked animals “usually results in a lowered immune response, and thus higher viral loads”.

Changing motivations for hunting

According to Haq, the Himalyan monal is a prime example of a creature that was largely hunted for self-consumption and is now hunted for trade. “Poachers think that if they sell the meat, instead of eating it, they can make some money,” he explained.

Himalayan monals are, as the name indicates, native to the Himalayan region. These birds are a prime example of the shifting motivation for hunting from self-consumption to trade

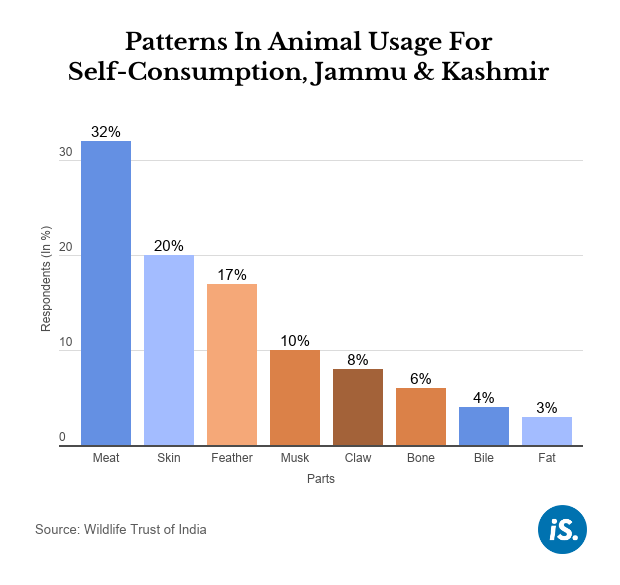

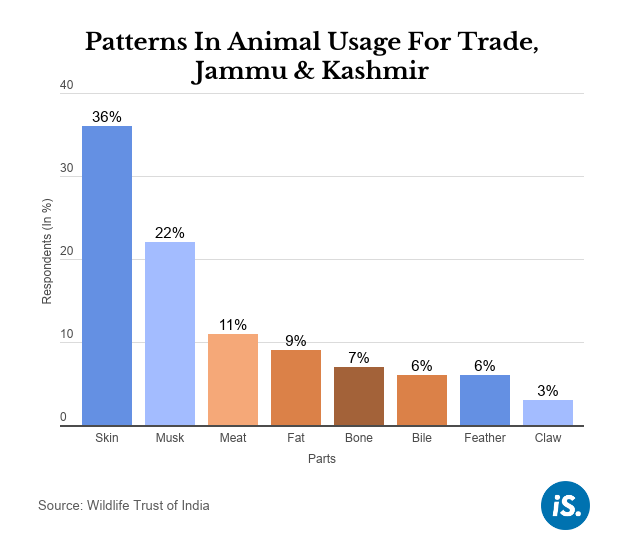

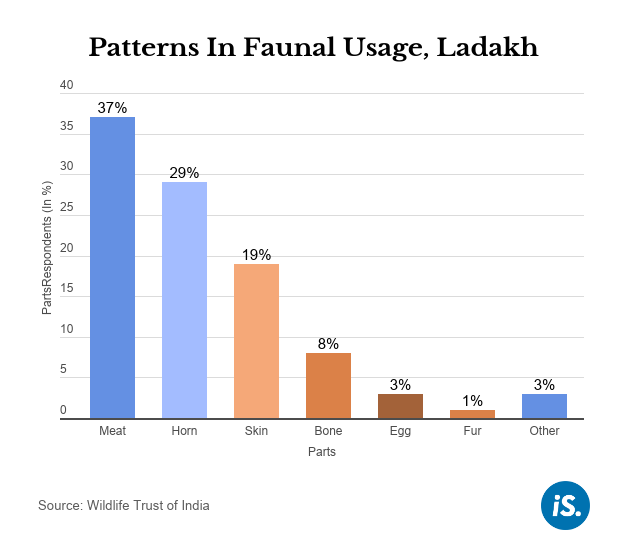

Haq found--through 243 interviews in Jammu and 185 in Kashmir--that while seeking meat for self-consumption is still the biggest motivation for hunting wildlife (in 47% of cases), hunting for trade is gaining ground, and is the motivation in 14% of cases. When hunters target wildlife for self-consumption, their meat is the preferred reason, whereas when the motivation is commercial, their skin is the most-sought after.

Black bear fat is used as traditional medicine.

Retaliatory killing, where wildlife like leopards are hunted because of threats to human life, cattle, etc., also poses a significant threat, according to the WTI study. In fact, human-wildlife conflict is the second most common reason for hunting wildlife.

With the growing appetite for commercial trade, it is likely that higher numbers of species may be hunted and poached than before, the experts warned.

Inter-state and inter-agency cooperation needed to protect wildlife in J&K

Given the dominance of the conflict in the region, and the preoccupation of enforcement agencies with it, preventing wildlife trade has not been given the kind of attention it deserves, Jose Louies, a conservationist with WTI, pointed out at the workshop. J&K has experienced conflict since 1947, with India and Pakistan fighting wars over it, and a separatist struggle developing in the Kashmir Valley.

Riaz Ahmed, another conservationist with WTI--under whose guidance the J&K study was conducted--stressed the importance of gathering baseline information about what, where, why and how wildlife poaching is taking place in Jammu and Kashmir and how it can be controlled. “In any crime, the toughest thing is to understand what is happening,” Louies added.

Both the study and the workshop are part of the SECURE Himalaya Project, a combined effort by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Global Environment Facility, an independent fund set up on the eve of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit to provide grants for projects related to biodiversity, climate change, etc. In India, the project focuses on four regions--Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Sikkim, and aims to secure livelihoods by focusing on conservation, sustainable use and regeneration of ecosystems in the higher ranges of the Himalayas.

The Jammu workshop, focussing on the prevention of wildlife trade, was organised by WTI in collaboration with the Department of Wildlife Protection under MoEFCC and the UNDP. Attendees included officials from the J&K forest department and police, and from the Border Security Force, Central Reserve Police Force, the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau and other relevant agencies. There was wide agreement on the importance of inter-state cooperation, since wildlife trade in all northern states is inter-connected, and for cooperation between various agencies as well.

“Wildlife crime happens in a chain from poaching to transportation to selling and we have to disrupt this process at various levels,” Arun Kumar Choudhary, additional director general of the Armed Police in J&K, said at the workshop.

“We need to provide training to the wildlife department to deal with crime and investigation… we don’t receive the kind of training that the police department or other investigative agencies receive,” Amit Sharma, the Jammu wildlife warden said. “We also need to be taught how to do crime scene investigations, how to draft a report and how to present the findings before a court,” he added.

Covert study

The WTI study was based on extensive field surveys and literature reviews and was conducted covertly, rather than using the routine method of filling out questionnaires, where the participants know the intent behind the questions that they are being asked.

“We didn’t ask people if they poached or hunted,” Haq explained. “We asked how local wildlife was being used, and people told us that they sought the animals for meat, musk, skin, etc.” When asked if they also traded in these items, they revealed that they mostly used the skin for trade, followed by bones, musk and bile.

The trade in the skin, teeth and nails of leopards was especially profitable, Haq noted. The team also pointed out that shahtoosh, a type of shawl made from the wool of the endangered Tibetian antelope (locally called the chiru), was still being made and sold, despite the chiru being accorded the highest level of protection under the WLPA.

Global trade in shahtoosh has been banned under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), an international agreement to restrain the trade of certain species of flora and fauna, since 1979.

Turtle trade is also rising in the region, though the scale is not very large yet, Haq revealed.

Official records of wildlife trade in Jammu

Explaining his comments on the extensive poaching of leopards, Amit Sharma, the Jammu wildlife warden, said the 43 deaths cited by him relate to cases where seizures were made of animal parts or skin being traded. “But the number of leopards that have been killed in the last nine years is far greater,” he stressed. “There have been many other cases where people have killed leopards because they have attacked their cattle or a family or community member.”

Trade in live birds, especially in parakeets, is also an emerging threat, Sharma noted.

Parakeets are listed in Schedule IV of the WLPA, which means that even though the species is protected and activities such as hunting and captivity are prohibited, the penalties are lower than those imposed for Schedule I species such as tigers and elephants.

“It is an inter-state crime,” Sharma emphasised. He explained that the birds were caught in places such as Jalandhar in Punjab, or in parts of Uttar Pradesh, and then brought to Jammu.

Trade in parakeets and, in general, pet trade in birds is an emerging threat in Jammu and Kashmir.

“Many snake charmers also bring snakes into Jammu city and this happens a lot during Shiv Ratri... once there was a case involving a python,” Sharma added.

Pythons are protected under Part II of Schedule I of WLPA, which specifically prohibits activities such as acquiring, receiving, keeping in custody, and possessing of the listed species, unless prior permission has been sought from the concerned authority.

Patterns in plant trade in Jammu and Kashmir

The report and the Jammu workshop also drew attention to the trade in plants in J&K, among them saussurea roylei, bergenia stracheyi and trillium.

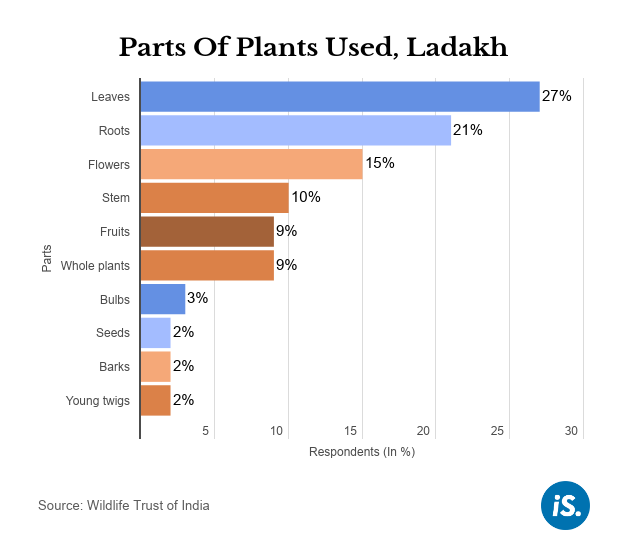

These plants are usually traded for their medicinal properties, and the major problem here is that the plant part being used or traded the most is the root, Haq said. When the root stock is removed, the plant’s capacity to regenerate is reduced and the entire population stands impacted.

Contrary to common belief, the term “wildlife” refers to both plant and animal life. The WLPA says wildlife “includes any animal, aquatic or land vegetation which forms part of any habitat”.

The list of plant species protected under WLPA contains only six species, and does not include the ones most traded in J&K. However, conservationists have called for a special law to protect plant species with medicinal properties.

This trade was not a problem specific to J&K or Uttarakhand or Himachal Pradesh or Punjab, Haq stressed. For example, plants are poached in Kashmir for sale in Amritsar, in Punjab, and transported across state borders by several routes. Thus, as with animals, curbing the trade in plants required cooperation at the regional level rather than just at the level of each state.

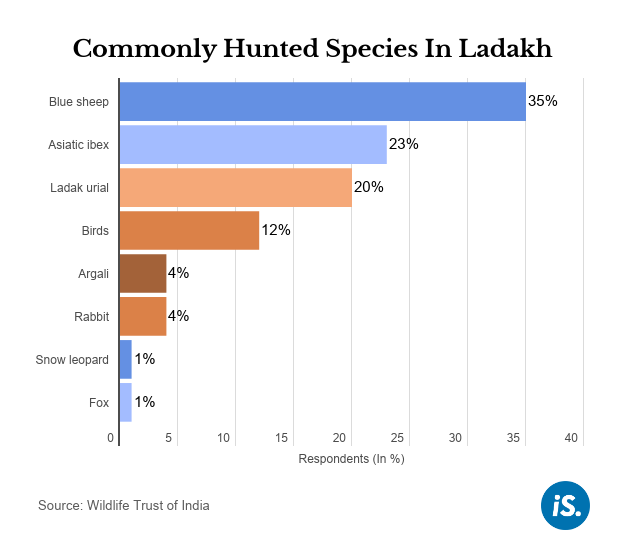

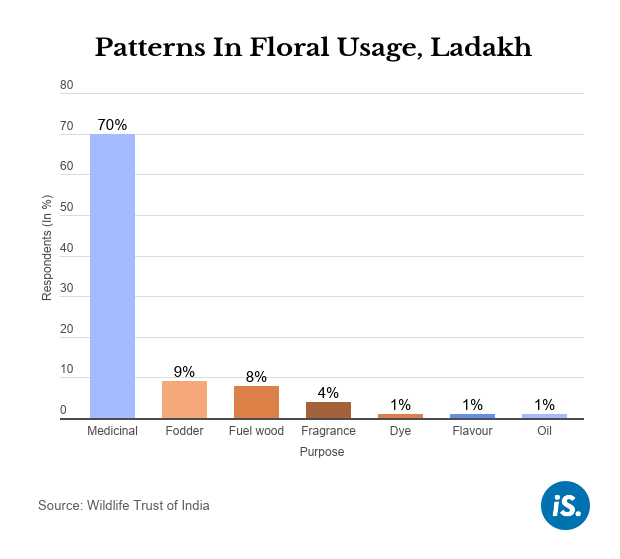

Wildlife trade in Ladakh

The WTI team had also conducted a three-month study of wildlife trade in the adjoining union territory of Ladakh in 2019. The team found that the most commonly hunted species included the blue sheep, Asiatic ibex and the Ladakh urial and that these were largely poached for meat and horns.

Commonly hunted birds included the Himalayan snowcock, Tibetan snowcock, chukar and wild pigeon while apex predators (those at the top of the food chain) such as snow leopards and brown bears were hunted for trade or due to human-wildlife conflict.

As for trade in plants, key species included aconitum heterophyllum, saussurea roylei, inula racemosa, rheum spiciforme and rheum webbianum, whose leaves and roots were largely used for medicinal purposes.

Here, the biggest use was self-consumption (65%) rather than trade (35%).

Trade routes for poaching wildlife include the Leh-Srinagar highway, the Leh-Manali highway, Amritsar to Dharamshala to Leh to Srinagar, Tibet to Chumur to Karzok to Himachal Pradesh to Srinagar, Tibet to Nepal to Uttarakhand to Delhi to Srinagar and Darchula to Khatima to Delhi to Srinagar.

(Pardikar is a freelance journalist from Bengaluru.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.