How Online Sale and Global Supply Chains Of Paint Brushes Are Endangering India’s Mongooses

Bengaluru: Millions of paint brushes are sold to students and professionals across the world every year, but not many know that a sizeable proportion of these are made from the hair of mongooses poached from India. Now e-commerce is further escalating the threat to the animal by reducing the visibility of the trade, an ongoing study shows.

“The biggest problem with online trade is that we literally have no clue how it is happening,” said Shaleen Attre, a conservation consultant and currently a visiting researcher at Oxford University.

As a student at the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, University of Kent, UK, Attre conducted a five-month study in which she ordered paint brushes online--both via e-commerce platforms and directly from retailers in the UK. Through microscopic analyses of all the 46 sample brushes she collected, she surmised that the hair belonged to the herpestes species of mongooses found in India.

In addition to the UK, Attre also checked a few European markets and researched inputs from Indian experts. Using interviews, online research, surveying brick-and-mortar stores and conducting microscopic analyses, she has written a paper that is listed for publication.

“What we know today is that large-scale poaching of mongooses is happening only in India,” Attre said, an assessment that H.V. Girisha, regional deputy director, Wildlife Crime Control Bureau, agrees with. An organised supply chain and a relevant knowledge base in the various processes--collection of mongoose hair, its sorting and packaging for national and international markets, and so on--has been detected only in India, she said.

So, it is very likely that India is satisfying the global demand for mongoose hair paint brushes, Attre concluded.

About 100,000 mongooses are poached every year in India, according to estimates from the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), a Noida-based conservation organisation. A single mongoose yields about 40 gm of hair and of this, on average, only about half is considered of paint-brush quality.

Mongoose hair brushes are usually preferred by artists for their quality. “Mongoose hair is very unique in water-holding capacity,” said Mamta Rawat, wildlife biologist at the Ecology, Rural Development and Sustainability Foundation, a Rajasthan-based grassroots NGO that works for biodiversity conservation.

Latest raid yielded 54,000 brushes, 133 kg of raw hair

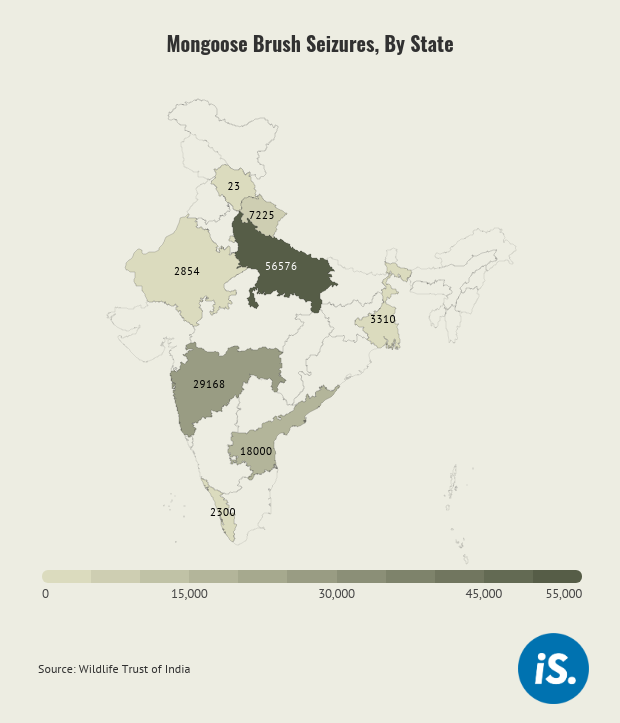

Within India, there are a handful of paintbrush manufacturers and it is largely a traditional business. Until recently, one of the biggest paintbrush manufacturing hubs was in Sherkot in the Bijnor district of western Uttar Pradesh.

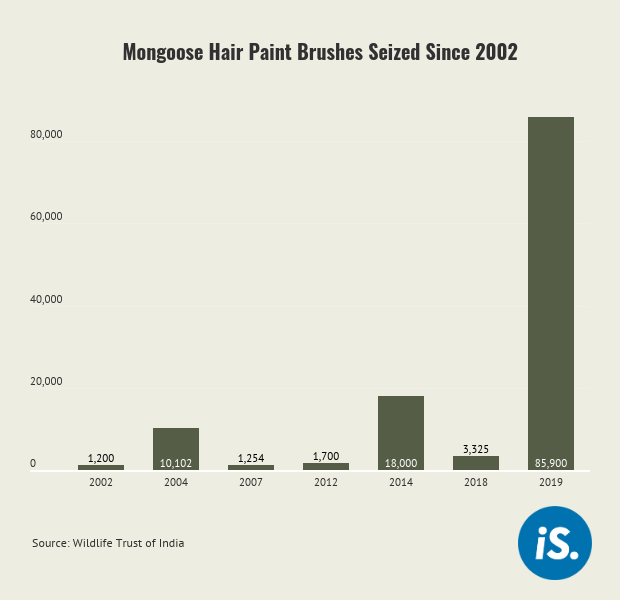

In October 2019, the WCCB, with the assistance of WTI’s volunteer network, conducted raid-and-seizure operations in Sherkot that resulted in over 40 arrests, seizure of over 54,000 brushes and 113 kg of raw hair, and the shutting down of 10 brush manufacturing units.

The raid is the biggest one yet on the mongoose network where officials simultaneously targeted manufacturers and suppliers across four states--Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Kerala--on a single day.

Other such operations have been conducted in the past but though they may have disrupted supply-chain linkages, online trade is harder to curb because “there is a huge missing link between online retailers and their suppliers”, Attre said.

Brushes manufactured in places such as Sherkot are smuggled to other states--Karnataka, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu have been clearly identified, among others--from where they are exported to the European and US markets, Jose Louise, a conservationist with WTI, told IndiaSpend.

Cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Ahmedabad and Kolkata also fall along export routes, Rawat noted. “Lately, Indo-Nepal and Indo-Bangladesh routes have also been found [to be] lucrative by smugglers,” she added.

Exports to western markets are also suspected to be made via China, Attre explained.

Illegalities, regulatory ‘grey areas’ in the trade

Domestic trade in mongoose hair is illegal and all six species of mongooses found in the country--the common grey mongoose, ruddy mongoose, the small Indian mongoose, crab-eating mongoose, stripe-necked mongoose and the brown mongoose--are protected under Part II of Schedule II of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972.

Penalties for violation include a jail term of three to seven years and also a fine of at least Rs 10,000. This is the same level of penalty that is accorded to cases concerning Schedule I species such as tigers and elephants, which are accorded the highest level of protection.

Earlier, mongooses were listed in Schedule IV of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 but then their status was upgraded to Part II of the Schedule II in 2002--entailing higher penalties for more serious violations--when it became apparent that trade in mongoose hair was rampant.

“Trade in mongoose hair was first unearthed in the country sometime in 2001,” Louise said. “Since then, large-scale trade in mongoose hair by big manufacturing companies has reduced but the trade is still thriving because the demand [for mongoose hair] exists.”

Poached in India, packaged in Mauritius

Internationally, Indian mongooses are listed in Appendix III of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an international agreement to restrain the trade of certain species of flora and fauna. This means that while international trade in mongooses is permitted, it is regulated, i.e. those trading in mongoose hair are required to obtain permits to do so.

But CITES only provides norms and has no enforcement powers in individual countries, and Appendix III is the lowest level of protection that CITES offers. Only the six Indian mongooses and two from Pakistan are listed in the Appendix.

This is where it gets tricky because the species of mongooses that are found in India are also now being found in places such as Mauritius and Hawaii, where they are not native. And so, ascertaining origin becomes difficult.

“The packaging on a lot of the brushes that I ordered stated that the manufacturing was done in Mauritius,” Attre explained. “But what I learnt from my sources in Mauritius is that there is no information about active mongoose hair brush manufacturing hubs in the country.”

Taxonomically, too, it is very difficult to ascertain if mongooses belong to a certain species that are found in India or are a subspecies because there is very little research being conducted into mongooses in India. “We have no idea how many mongooses are present in India and what their distribution is,” Louise said.

“The impact of wildlife removal [whether] for trade or for subsistence from their habitats are not known for most species,” said Rahul Kaul, chief of conservation at WTI. “This is because baselines for most species do not exist.”

No population estimates

The central government, specifically the National Tiger Conservation Authority and those involved with Project Elephant, formally estimate the tiger and elephant count in the country while individual states may conduct annual estimates of certain species of their interest, such as the hangul (Kashmir stag) in Jammu and Kashmir or the rhinoceros in Assam.

Additionally, some estimates for tiger prey populations such as the deer become available because this is captured while conducting tiger estimations. But most other species are largely ignored.

At times, experts undertake population estimates for a species of their interest such as dolphins or gharials, vultures, the Great Indian Bustard, etc., Kaul explained. But “mongoose species, in addition to hundreds of other species, have no estimates”, he added.

“Even to push for higher protection in CITES to stop international trade, we will have to establish that their [mongoose population] numbers are going down and that the biggest reason for this is the current level of trade,” Attre said.

The second problem is that at an international level, mongooses are considered ‘pest species’. “In Mauritius, culling programmes are under way to control mongoose numbers,” Attre said.

Identification troubles

Essentially, mongoose hair samples from India have to be put on record at customs offices and DNA or microscopic analyses have to be conducted on the suspected hair to prove its origins, Attre explained. And because mongooses are not a priority internationally, there is little willingness to go through these processes, she added.

Adding to identification troubles are those dealing in mongoose hair who misrepresent the hair as from badgers, polecats, hogs and sable. “A staggering number of animals are used in the manufacture of paint brushes,” Attre said. Because of pressures from India, there is some pushback against the unethical usage of mongoose hair but the same is not true for the usage of other kinds of animal hair, she added. Faux mongoose hair brushes with both real and synthetic hair are also available in the market and this further exacerbates identification problems. The samples that Attre found indicative for containing mongoose hair were also mixed in with synthetic fibres.

Such identification issues need to be addressed because customs officials around the world are not always trained to identify parts of small mammals such as mongooses, Attre said. Consumers must also be made aware. “From what you see, you cannot imagine that there is a big crime…this is the level of ignorance,” Girisha said.

Within India, the general trend is that either people are completely unaware of the fact that paint brush manufacturers use mongoose hair or they do not know how to distinguish mongoose hair brushes from synthetic ones, Girisha and Attre noted.

Mongoose brushes can be identified easily because their features are distinctly ‘salt and pepper’. The hair has shades of grey, cream, brown and dark brown which all seem like a mosaic of black and white. The tips of mongoose hair brush are dark brown, the centre is cream or greyish while the roots are dark.

Mongoose brushes can be identified easily because their features are distinctly ‘salt and pepper’.

The mongoose population also suffers because of the lack of attention from the forest department and other enforcement agencies. “It’s a question of priority,” Attre explained. “Mongooses are one of the many species that are ignored... There are others like monitor lizards and star tortoises which are poached in massive numbers.”

Perceptions might be changing, though. “Among the younger generation [of students and artists], I have noticed that there is a pushback against using mongoose hair brushes,” Attre said.

(Pardikar is a freelance journalist from Bengaluru.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.