How Modi’s Govt Is Scrapping A Scheme Gujarat Benefited Most From

India’s urban Development Minister Venkaiah Naidu announced recently the new BJP-led Government would be scrapping the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), an urban infrastructure fund and brainchild of the previous government. He claimed it was too centralised and did not allow states much space for policy maneuvering.

The Government now plans to launcha new mission which will focuson “spatial planning, liquid and solid waste management and public transport, among other things.”

The JNNURM might have faced glitches but it provided a useful proxy, including to folks like us, to gauge urban infrastructure investment and build across cities like India.

We have two key findings to report from the latest available numbers. First, the state of Gujarat led by now Prime Minister and former Chief Minister Narendra Modi for more than a decade until May 2014 was actually one of the largest absorbers of JNNURM funds and used it effectively to build infrastructure in its cities. Second, the city of Bangalore now has the maximum number of completed projects, overtaking Ahmedabad and Surat, which led the league tables until last year.

So, what has been the story of JNNURM since itslaunchin 2005-06? The aim of JNNURM was to improve cities across the country by developing physical infrastructure and local governance. Though the programme was to end in 2012, it was to be extended by two years to 2014 if the previous Congress-led UPA Government were to be elected.

So what has been the story of JNNURM since its launch in 2005-06? JNNURM’s objective was to improve cities across the country by developing physical infrastructure and local governance. Though the programme was to end in 2012, it was to be extended by two years to 2014.

The mission was initially divided into two sub-missions:

1. Urban Infrastructure and Governance (UIG); and

2. Basic Services to the Urban Poor (BSUP)

Two other components were added later to accommodate more cities and towns:

1. Urban Infrastructure Development for Small and Medium Towns Scheme (UIDSSMT); and

2. Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme (IHSDP).

A reportby the Government’s auditor, Comptroller & Auditor General (CAG), says the mission was allocated Rs66,084 crore by the Planning Commission between 2005-06 and 2011-12. As against this, Rs45,066 crore was the actual budgetary allocation during the same period. And nearly 90% of the budgetary allocation (Rs 40,584 crore) was released for the various programmes of the mission.

So which states and cities have completed the maximum number of projects?

Tamil Nadu has completed the maximum number of projects (102) out of the 136 sanctioned projects followed by AP with 70 out of the 84 projects under UIDDSMT.

Bangalore completed the highest number of the projects (23) out of 38 sanctioned projects followed by Ahmedabad and Surat with 22 and 19, respectively. Note that Bangalore, Kolkata and Chennai are larger cities and Ahmedabad and Surat have clearly been more effective in sourcing and utilising the funds. Ahmedabad has completed only 4 projects since 2012 when we had reported earlier 19 completed projects.

Financial Management

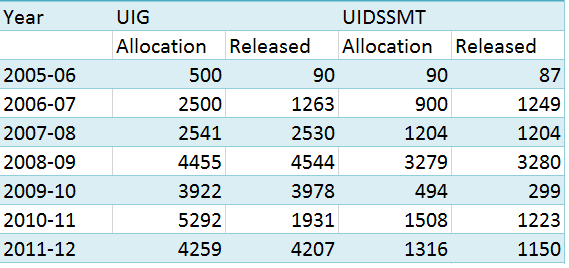

The table below shows the funds released under additional central assistance (ACA) from 2005-06 to2011-12 for UIG and UIDSSMT.

(Source:CAG )

A total of 79% (i.e. Rs 18,543.66 crore) was released under the UIG component out of the total budgetary allocation of Rs 23,469 crore. And 83.5% (i.e. Rs 7,342.96 crore) were released under the UIDSSSMT component of the total budgetary allocation of Rs 8,792.2 crore.

Under the JNNURM the funding pattern, the centre pays 35%, the state pays 15% and the urban local body or the municipal corporation pays 50% of the project funding.

According to the CAG report, funds released were dependent on the condition that reforms would be implemented by urban local bodies (ULBs). This was not done by most states and hence the delay in release of funds to the states. Another reason for the late release of funds was the seeming delays in approval process of the central Government and the inability of the state Governments to complete the requisite formalities.

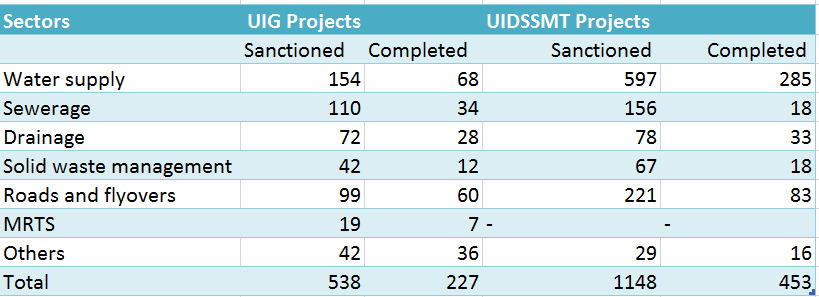

So, how many projects were sanctioned and how many were completed under JNNURM?

Out of 538 sanctioned projects under UIG, only 227 were completed. The maximum projects completed were under water supply (68) and roads and flyovers (60). Out of 1,148 projects sanctioned under UIDSSMT, only 453 were completed. Here again, the maximum projects completed were under water supply (285) and roads and flyovers (83).

Let us now look at the problems faced by the programme:

Diversion of funds: Funds released by the central Government were utilised for other purposes ranging from payment of bills and salary to municipal employees to compensatory forestation, which was not covered under JNNURM. For example, in Jharkhand, JNNURM funds were used to pay salaries to municipal staff.

Diversion of funds for private land acquisition: JNNURM did not provide money for private land acquisition as the burden of this was to be borne out by the state governments and ULBs with the exception of states of J&K, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, North-Eastern states. In Haryana, the CAG noticed that JNNURM money was used to acquire private land for building collector wells for over Rs 200 crore.

Challenges

JNNURM brought to light the urban realities of India, and it also brought out several challenges in the field of urban development. A key challengehas been capacity building. This was one reason why many states were not even applying for the grants. The states that did apply for the grant and managed to get their projects sanctioned could not complete the projects due to lack of human resources.

Another important challenge, which was highlighted by the CAG report, was the inability to raise finances for projects. Under JNNURM, the central Government was to provide a certain percentage of the approved cost of the projects while the rest was the responsibility of the state Government and the urban local bodies. Many urban local bodies simply could not raise their share of finances because they lacked the organisational structure required to raise finances. They were dependent on grants from state Governments to carry out daily order of business.

States with past experience of implementing large urban infrastructure projects with multilateral agencies responded immediately to the mission and availed of its benefits. This helped them move faster in preparation and implementation of projects under JNNURM; for example Gujarat and Maharashtra.

Conclusion

The new Government, which plans to build another 100 metros, has to keep in mind the new urban realities, and also tackle the issue of capacity building - not only of states but also of urban local bodies. The lessons from states like Gujarat and Tamil Nadu might be well applied elsewhere.