For A Dying Silicosis Patient, A Mining Fund Offers Hope

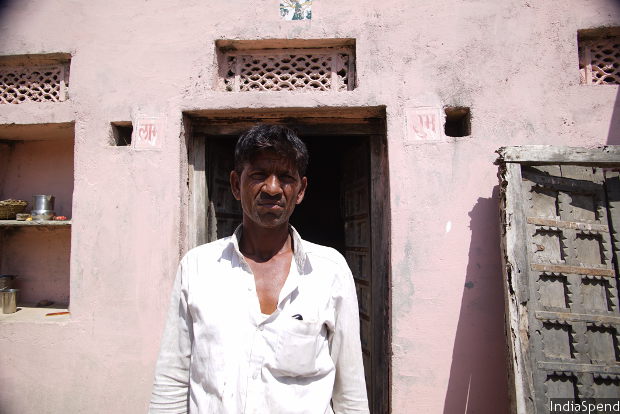

Deva Singh, 40, of Pratappura village in Bhilwara, Rajasthan, is unable to work because of silicosis. He caught the debilitating, untreatable disease from working at a sandstone mine without any protective gear, as is common across all kinds of mines all over India.

Pratappura village (Bhilwara district), Rajasthan: In the early 1990s, at the end of a drought that stretched over three years, an 18-year-old Deva Singh took up work at a nearby sandstone mine. He was grateful for the Rs 15 a day it paid because there was no other work in his primarily agricultural village. Now 42, Singh has been diagnosed with silicosis, a disease caused by fine silica dust released from mineral mining operations, for which there is no cure.

At the mine, Singh and fellow miners were given no protective gear. Within 10 years, his body had given up. “My back would hurt, my ribs would ache,” Singh told IndiaSpend. The disease claimed the life of one of Singh’s brothers, and another brother has recently been diagnosed with the disease. Singh returned to his village 6-7 years ago, and now spends the day grazing the two goats his family own. The household runs on the Rs 200 a day his wife and daughter each earn as hired farm hands.

There are more than 30 people from this village alone, and at least 1,000 across Bhilwara district, who have contracted silicosis from working in mines, and whose livelihoods and lives will never recover.

It is to help such casualties of India’s mining sector that the Pradhan Mantri Khanij Kshetra Kalyan Yojana (PMKKKY, or the Prime Minister’s Mining Area Development Programme) has been conceptualised. Operational since 2015, the programme empowers India’s mining districts to levy a charge on all mining operations to create a fund that would be used to mitigate the harmful effects of mining and to benefit local people.

In 2014, mining employed over 500,000 people in formal jobs, according to the National Sample Survey Office, and is expected to create 13-15 million more jobs by 2025, according to this government strategy paper for the ministry of mines.

Barring a few exceptions, India’s mineral-rich areas are also its poorest. Mining has not only failed to benefit local residents, it has degraded lands and rivers and destroyed traditional livelihoods, while illegal mining is widespread.

In the first of this two-part series, IndiaSpend visits Bhilwara district in Rajasthan to understand the issues that the programme must address.

Mining, in India and in Bhilwara

India’s rich mineral wealth has made mining a lucrative industry in India, especially since the commodity price boom of the 2000s which has, however, tapered lately. A 1% increment in the growth rate of mining and quarrying results in a 1.2-1.4% increment in the growth rate of industrial production and a 0.3% increment in the growth rate of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

However, India’s major mineral reserves lie under forests and near river watersheds, making extraction environmentally fraught. Some of the most mineral-rich states--Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Odisha, for instance--have remained the poorest as mining has not benefitted local communities, and federal and state governments have failed to utilise mining taxes and cesses for growth and development.

“Mining related operations largely affect less developed and very remote areas of the country, and vulnerable sections of the population, especially Scheduled Tribes,” the government order creating District Mineral Foundations said on September 16, 2015, adding, “therefore, it is especially necessary that special care and attention is devoted, in an organized and structured manner, to ensure that these areas and affected persons are benefited by the mineral wealth in their regions and are empowered to improve their standard of living.”

Bhilwara, which got its name from the Bhil tribals who once lived here, is dotted with some 500 sandstone mines and 1,000 zinc, lead, silver, mica, feldspar, soapstone and other mines, which provide raw materials for everything from cars and insulation bricks to vitrified tiles and cosmetics.

The district has one of the largest zinc deposits in the world, and is a thriving textile centre. Yet, more than half its women were illiterate, 35% of its children were stunted, and 67% village women aged 20-24 years had married before the legal age of 18 years in 2015-16, according to the latest National Family Health Survey. The district of 2.4 million residents remains largely rural--78.7% of its residents live in rural areas.

Minerals and mines cover at least 9,218 hectares of land, according to this government report. While mineral extraction has degraded land and water, created pollution, and caused health issues, the water in many villages is naturally contaminated with fluoride.

As much as 85% of Bhilwara is affected by mining and its undesirable fallouts, Kamleshwar Baregama, the senior mining engineer with the government who is also the secretary-general of the two committees that run the District Mineral Foundation, told IndiaSpend. This includes villages on or near mining lands, areas lying in the path of wind or water flow from mines, as well as mining dispatch regions such as the paths of trucks ferrying minerals.

A map of Bhilwara district that hangs in a government mining office in Bhilwara, Rajasthan. 85% of Bhilwara district is affected by mining, and is eligible to receive aid from the Pradhan Mantri Khanij Kshetra Kalyan Yojana.

What the funds could do

District Mineral Foundation (DMF) “is a revolutionary idea”, said Chandra Bhushan, deputy director general of Delhi-based environmental research and advocacy group Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), which has been tracking DMFs across India and is helping some districts make a plan for spending DMF funds. It is “an idea which says that the people have right to benefit from the natural resources”, he said.

By August 2017, DMFs had collected over Rs 11,028 crore ($1.69 billion) across 12 mineral-rich Indian states.

Bhilwara district had collected Rs 400 crore by October 2017.

Source: Data collected for the Ministry of Mines and Planning CommissionNote: Figures for Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Telangana and Tamil Nadu are collections until August 2017. The rest are collections until May 2017.

It took Deva Singh two trips to Bhilwara city, 80 km from his village, to get a certificate from the overcrowded government hospital that would entitle him to receive Rs 1 lakh from the government. His family would be eligible to receive Rs 3 lakh on his death.

“What will 1 lakh rupees do? It’s so expensive nowadays,” he told IndiaSpend as he sat under a tree outside a neghbour’s house on a sunny October day. “We need Rs 5,000 a month for the family to survive. And that’s without the cost of educating our four children,” he said, adding that his family have had to borrow Rs 2-3 lakh for his treatment from the local farmers’ cooperative and from moneylenders.

PMKKKY funds, though managed by the local government, are different from other government funds in that they do not lapse--the money unused at the end of a year can be used in subsequent years. Although there are priority areas listed under the law, it is up to each district to decide how to spend its funds.

Kalu Lal Gurjar, a Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) member of the legislative assembly (MLA) from Mandal, a constituency in Bhilwara, has requested Rs 36 crore for roads, which he considers the main problem in the area, as well as Rs 1 crore for primary health care centers, Rs 1 crore for drinking water-related issues and Rs 15-20 lakh to construct classrooms in schools that expanded to include higher secondary classes without creating space. “On average each constituency should receive Rs 40-50 crore,” he told IndiaSpend.

Residents of Nayanagar village in Jahazpur constituency, who had not heard about the Yojana until IndiaSpend mentioned it, said water shortage was their most pressing problem and the fund should help solve it. “This year because of the poor monsoon, we already have a water problem,” Prabhu Lal Gurjar, who lives with his family of five in Nayanagar, told IndiaSpend in October 2017. Water shortage usually begins in May in this region.

“The Hindustan Zinc plant in Agucha uses 10 million litres every day from the Banas river, which has reduced the level of water here,” Dheeraj Gurjar, the Congress MLA from Jahazpur, said. Hindustan Zinc’s environmental clearance for the mines gives it permission to withdraw 11.7 million litres a day from the Banas river. A senior company official said they use about 8-10 million litres a day for the mine and for drinking water, recycle 50% of this water for reuse in the mining process, and also harvest rainwater.

Water in the village is also contaminated with fluoride, as per Jahazpur’s public health engineering department. Long-term ingestion of fluoride can cause stained and pitted teeth in children, pain in the joints and even bone deformities.

Prabhu Gurjar lives with his family of five in Nayanagar village in Bhilwara, Rajasthan. “This year because of the poor monsoon, we already have a water problem,” he told IndiaSpend in October. The arid season usually begins in May in this region. Gurjar suggested that the mining-area development fund be used for groundwater recharge.

In Samodi village, residents said the major problems are shortage of grazing land, shortage of water for irrigation, water contamination that reduces crop yield, and unemployment. Villagers blamed a nearby iron ore mine and pellet-making plant operated by Jindal Saw Ltd. for the water shortage and contamination. They also said Jindal does not provide fodder in lieu of the grazing land that came under its lease, does not properly maintain the fodder plot it has provided, and does not provide adequate employment in the village.

A Jindal spokesperson said the operations require 8-9 million liters of water a day, which are obtained from recycled sewage water for which Jindal Saw pays Rs 6 crore (Rs 60 million) to the municipal corporation. It also uses a borewell to withdraw 12,000 liters of drinking water a day. “The process of separating the mineral is water based and does not use any chemicals which could pollute the water,” the spokesperson told IndiaSpend, further claiming that 70% of those employed in the mines and plants are from Bhilwara district and that the company has provided a fodder plot for Pur, Samodi and Dariba villages.

The DMF presents an opportunity for mining companies to win acceptance from communities, Akshaydeep Mathur, honorary secretary general of the Federation of Mining Associations in Rajasthan, told IndiaSpend. “If the district mineral foundation is used in the right fashion and judiciously, it is a good scheme which will benefit mining areas. It will also help mining companies do business in a smoother fashion,” he said. “If you can see the benefit to you from the mine, you will be more open to it.”

But some mining companies are opposing it

“We are already paying other taxes, royalty to the government, what are they doing with that money if not using it for the development of the people?” R K Sharma, secretary general of Delhi-based Federation of Indian Mining Industries (FIMI), which is opposed to the idea of the DMF, told IndiaSpend.

For the DMF fund, companies mining major minerals (such as copper, tungsten and coal) must pay an amount equivalent to 30% of the royalty of a mine leased before 2015, and mines leased after 2015 as well as those mining minor minerals (such as marble and granite) must pay 10% of the royalty.

Sharma said mining companies make enormous expenditure on mineral exploration, as well as opening up and operation of a mine, adding, “The whole taxation system is too high and needs a revamp. Even after paying so much, mine companies have to develop infrastructure in the areas they mine in, what is the point of paying to the government?”

The central government issued a notification regarding DMFs in September 2015, but said funds would be collected retrospectively from January 12, 2015, when the Mines and Minerals (Development & Regulation) Amendment Act, 2015, came into force. Some mining companies have contested this and the case is currently being heard at the Supreme Court.

“The issue is that the government seeks to collect it for the period when the law was not notified and the foundations were not operational,” Abhishek Manu Singhvi, senior advocate and counsel for FIMI, said, adding that companies are paying the levy from the date of the notification (September) without protest.

Not all mine owners are opposed to the levy, however. “It’s not a big issue,” said Rajendra Deedwaniya, owner of two mines in Bhilwara district, who said the levy has raised mineral prices but it would work in the interest of the mining industry in the long-run, “If the money is allocated well, the fund will be very useful.”

Deedwaniya said the mining industry has seen enough growth to sustain the business--his family has worked in the mining sector since 1984--and it is the overall state of the economy which impacts the industry, not a payment such as for the DMF.

Back in Pratappura village, IndiaSpend accompanied Deva Singh as he visited a fellow miner, Narayan Singh, 34, who has also contracted silicosis. “There is no respite now. Even the doctors have given up,” Lila Singh, the ailing miner’s mother, said of her son as he lay coughing on a charpai, puffing on an inhaler to help him breathe. (Narayan Singh died 15 days after we spoke to him. Please see update at the end of the story.)

Narayan Singh will leave behind a wife and six children, the youngest 10 months old. He can only hope that they get their fair allocation from the mining fund.

Update:

- Narayan Singh, the mine worker suffering from silicosis, passed away in his home on October 21, 2017.

- The Supreme Court ruled, in an order dated October 13, 2017, that governments could not ask mining companies to pay a retrospective levy from January 2015 for district mineral foundations (DMF). Companies should make payments from September 17, 2015, when the government issued the notification for the creation of the fund, irrespective of when a particular state created district mineral foundations. In the case of Rajasthan (and Bhilwara) this would mean mining companies pay a levy from September 17, 2015, and not June 2016 when DMFs were created in that state.

This is the first of a two-part series. You can read the second part here.

(This story is part of the Publish What You Pay (PWYP) Data Extractors programme. Shah, a writer with IndiaSpend, is a 2017 Data Extractor with PWYP, a group of civil society organisations working for an open and accountable mining sector. Ragini Bafna, an intern with IndiaSpend, contributed to this story.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”