First Demonetisation, Then Loan Waiver: Main Bank For Onion Farmers In Crisis

Customers line-up at the a branch of the Nashik District Central Cooperative Bank, but only a few are allowed to withdraw up to a limit of Rs 25,000--they must prove a medical emergency or marital need. A year after it was hit by demonetisation, the bank of choice for 70% of farmers in India’s onion belt in Nashik, Maharashtra, is struggling to survive, as are its customers.

Nashik (Maharashtra): In a normal October, Prabhakar Dhage--a manager in charge of recoveries at a bank that is used by a majority of farmers in India’s onion heartland--would receive new loan applications and process paperwork from agricultural societies. This is the time when farmers sow the rabi, or winter, crop.

Instead, as the monsoon of 2017 wound down, Dhage, 56, had no customers. When we met him, he was waiting for the state government to finalise a list of farmers eligible to have part of their loans cancelled.

“This year because the bank has no funds,” said Dhage, “there is no question of handling fresh loan proposals.”

This was not a normal October for Dhage, his bank, the Nashik District Central Cooperative (NDCC) Bank, or for Maharashtra, home to 12.5 million farmers.

A year after it was hit by demonetisation, the NDCC bank, the financial institution of choice for 70% of farmers in India’s onion belt, according to a director, is struggling to survive: Only 9% of loan repayments due have been made in 2017, compared to 70% in 2016, according to Dhage.

The NDCC bank is a bellwether for 371 such district central cooperative banks with 140,000 branches and 3.2 million customers nationwide; most were hit by demonetisation, in the aftermath of which the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) disallowed such banks from exchanging old notes, since the government feared they would become conduits to launder unaccounted money, to convert, in popular parlance, black money to white.

In Maharashtra, the finances of the NDCC bank--it had Rs 342 crore in its lockers until June 2017, after which the RBI said a limited amount could be converted to new notes--and other banks like it have been further affected by a loan waiver for farmers, who have largely stopped paying back loans.

The result: The 62-year-old bank that a majority of Nashik farmers with access to the formal banking system depend on is in crisis. Its cash reserves have fallen 78% over one year from Rs 100 crore in 2016 to Rs 22 crore in November 2017; it has loaned only 10% of the amount it did last year, and its bad debts increased 16%, from Rs 785 crore in 2016 to Rs 911 crore in 2017.

While the bank finances worsened, 96 farmers committed suicide in Nashik district over 11 months to 2017, an indication of a large and growing farm crisis.

Even as farmers get ready to sow the winter or rabi crop, Nashik District Central Cooperative Bank loaned Rs 300 crore in 2016-17 compared to Rs 3,367 crore in 2015-16.

Why district cooperative banks are important

Even as farmers get ready to sow the winter or rabi crop, Nashik District Central Cooperative Bank loaned Rs 300 crore in 2016-17 compared to Rs 3,367 crore in 2015-16.

Six weeks after the government removed 86% of currency, by value, from the economy on November 9, 2016, IndiaSpend reported how the restrictions imposed by the RBI on the NDCC bank had restricted the access of farmers to cash and loans.

Shirish Kotwal, Director, Nashik District Central Cooperative Bank,"We have 13.5 lac customers, 212 branches yet we are termed unreliable1/3 pic.twitter.com/P8P8s4UXs4

— swagata yadavar (@swagata_y) December 5, 2016

A year after demonetisation, we visited the bank again and found it spiralling further into crisis.

District central cooperative banks are part of India’s three-tier--primary, district and state--rural cooperative credit system, setup to ensure agricultural credit to farmers. Primary agricultural cooperative societies are not regulated by the RBI, but district and state cooperative banks are, with inspections conducted by the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), established 35 years ago to handle the RBI’s agricultural credit functions.

Source: National Federation of State Cooperative Banks Ltd.

The NDCC bank’s 212 branches are spread across Nashik district--which is three times the size of Goa and four times its population--many in remote areas.

“Many (account holders) have no other account,” Shirish Kotwal, director and former chairman of NDCC told IndiaSpend in 2016, referring to the fact that seven in 10 farmers with bank accounts were his bank’s customers.

On June 14, 2017, when the finance ministry allowed district central cooperative banks to deposit scrapped notes with the RBI within 30 days, 31 district central cooperative banks in Maharashtra alone deposited Rs 2,270 crore. But the ministry’s concession came with a rider: Only notes deposited after November 10, 2016, would be accepted.

“We still have Rs 22 crore in old currency that is lying with us,” said Kotwal in a phone interview in October 2017. “We are exploring legal remedies, so that it also gets deposited with the RBI.”

A year after demonetisation, bank’s troubles grow

It is not the Rs 22-crore stash of old currency that troubles the NDCC bank’s officials. It is the latest jolt to their finances that does. In June 2017, Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadnavis announced that loans up to Rs 150,000 would be cancelled, part of a nationwide rash of such waivers, which, as IndiaSpend reported in June 2017, were largely ineffectual.

Five months after Fadnavis’ announcement, the state government has still not finalised the list of eligible farmers, so, in anticipation of making it to the list, most farmers stopped paying their instalments.

In 2016, of the Rs 2,794 crore that the NDCC bank loaned to farmers, no more than Rs 252 crore had been repaid. “We had only 9% repayment this year compared to 70% each year,” said Dhage.

Even before the loan waiver, as market prices of farm produce declined because of a produce glut and imported onions, farmers were struggling to repay loans. Now, said Dhage, they have stopped all repayments.

“The process of loan waiver is straight-forward,” said Girdhar Patil, spokesperson for Nashik’s Shetkari Sanghatana, a farm lobby group. “Each bank sends a list of eligible farmers, and the government transfers money to the bank,” said Patil. “But here the government wants to indefinitely delay doing it.”

Fadnavis had announced in June that farmers would get a loan waiver before October 31, 2017, which would be the “biggest in Maharashtra’s history”. Even though the process of disbursement started on October 18, 2017, the process slowed down in a week’s time after 100 farmers were found to have the same Aadhaar number and other discrepancies in data.

“The process [of loan waiver] is computerised, the software rejects a form even if there is a spelling mistake, so the process of verification is taking time,” Subhash Deshmukh, minister of cooperation, marketing and textiles, also in charge of loan waivers, told IndiaSpend. He said Rs 370 crore has been deposited in the bank accounts of 55,000 farmers, and by second week of December, all eligible farmers would get the waiver.

At the heart of the unfolding bank crisis is a farming sector struggling to stay afloat.

As loans dry up, farmers flock to moneylenders

While the NDCC bank loaned Rs 3,367 crore to farmers in 2015-16, it disbursed no more than Rs 300 crore in 2016-17, said Raju Desale, district president of the Federation of Vividh Karyakari Vikas Sahakari Seva Societies, a federation of primary agricultural credit societies in Maharashtra.

Without credit, farmers use the services of moneylenders, who charge 5-10% interest per month for amounts up to Rs 20,000 for short durations like one to two months and 3-6% per month for amounts above Rs 100,000, he said. That means farmers may end up paying Rs 10 for every Rs 100 borrowed for short term. While Desale said 140 farmers committed suicides in Nashik in 2017, citing debt as a reason, the Asian Age reported 96 farmer suicides in Nashik till November 2, 2017, compared to 87 in 2016.

Withdrawals restricted, officials face angry customers

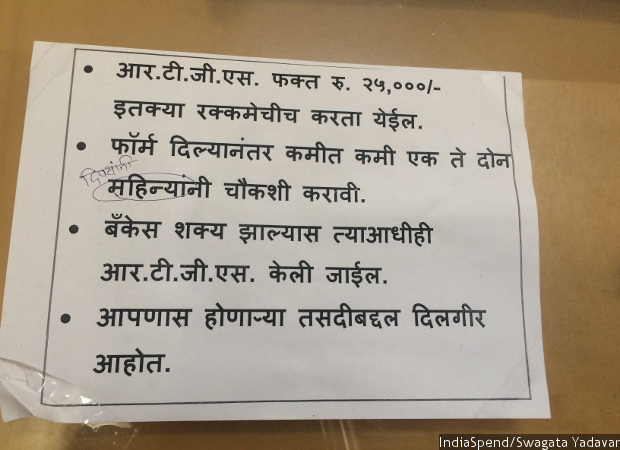

“RTGS [Real Time Gross Settlement] transactions allowed only up to Rs 25,000. Enquire after one or two months after submitting the form,” said a notice stuck at the NDCC’s head office at Dwarka, Nashik City. “Bank may complete the transactions earlier if possible. Inconvenience caused is regretted.”

With the bank’s cash reserves dwindling, its officials are restricting withdrawals. Customers line-up outside the bank’s branches, but only a few are allowed that limit of Rs 25,000—they must prove a medical emergency or marital need.

“RTGS [Real Time Gross Settlement] transactions allowed only up to Rs 25,000. Enquire after one or two months after submitting the form. Bank may complete the transactions earlier if possible. Inconvenience caused is regretted,” says a notice at the NDCC’s head office at Dwarka, Nashik City.

“I have been coming to the bank weekly since February,” said Kalpana Deshpande, a government teacher, who had come to the Nashik branch from Malegaon, 100 km to the north. “The NDCC account is my salary account, and I had saved for my daughter’s wedding.”

Government teachers in the district had their salary accounts with the NDCC bank. These accounts have now moved to IDBI, a public-sector commercial bank, but teachers said they were not able to withdraw the money from their NDCC accounts because of its cash crunch.

“Account holders are angry at us,” said Dhage. “At some branches, bank officials were locked inside, windows were broken, but they realised there is little we can do but wait for the bank to recover.”

Bias against DCCBs

This is not the first time that government action has weakened district central cooperative banks, said B Subrahmanyam, managing director of the National Federation of State Cooperative Banks a federation of central and state cooperative banks.

“RBI does not have a positive attitude towards district central cooperative banks because they are run by democratically elected representatives,” said Subrahmanyam. “It wants government officials to run DCCBs.”

The RBI believes such banks require oversight. In December 2016, during a Supreme Court hearing, the RBI said cooperative banks were not following KYC (know your customer) guidelines for account holders, and that was a leading reason why they were not allowed to exchange old notes. Another fear was that many politicians who are members of district cooperative banks could launder money through these banks, as the Times of India reported on June 22, 2017.

During the seven months it took them to deposit the old money, the district central cooperative banks approached the Supreme Court, which allowed the exchange of old currency notes--after KYC compliance of accounts and four verifications by NABARD.

“When the nationalised banks falling under RBI run by professionals had NPAs [non-performing assets] running into thousands of crores that the government had to recapitalise,” said Subrahmanyam, “How can they question the way DCCBs are run?”

(Yadavar is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.