Fighting Drug-Resistant TB: What India Can Learn From South Africa’s Successes

Johannesburg, Cape Town, Khayelitsha (South Africa): In July 2017, 40-year-old Noludwe Mabandlela, a single mother of two, collapsed at home. This ended up saving her life. The ambulance that responded took Mabandlela to the nearest government community health centre, where she was diagnosed with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). As the name suggests, first-line drugs such as rifampicin used to treat the more common, drug-sensitive TB don’t work on MDR-TB, from which patients have an increased risk of death and from which they take two years to recover, compared to six months in conventional TB.

Forty-year-old Noludwe Mabandlela, a single mother of two, received new TB drugs bedaquiline and delamanid for multi drug-resistant TB and, a year later, now hopes to make a full recovery. Here, she shows a photo of herself before she contracted MDR-TB.

Until then, an ailing Mabandlela--who lives in Khayelitsha, South Africa’s largest township, or informal settlement, 30 km southeast of Cape Town--had been going to a private hospital, where she was not tested for TB. Government health staff started Mabandlela on MDR-TB treatment, which included taking injectable drugs for six months. She developed side-effects from the drugs, including numbness in her feet, hearing loss and kidney impairment.

Mabandlela was then put on bedaquiline--the first new TB drug developed in nearly 40 years--through the South African department of health’s National TB Control Programme (NTCP). Since 2015, South Africa had started making the drug available in the NTCP for patients with extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB)--the most severe form of MDR-TB--and for patients like Mabandlela who developed severe side-effects from MDR-TB drugs.

Mabandlela also received another new TB drug delamanid from international humanitarian aid organisation Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF), in November 2017. These new drugs are still not commonly accessible--just over 24,000 of the world’s 558,000 MDR-TB patients have received bedaquiline till August 2018, and only 2,020 have received delamanid.

Mabandlela, HIV-positive and a cancer survivor, had almost given up hope as she lay hospitalised for a month. Now, over a year since her treatment began, she hopes to make a full recovery. Her story is a beacon of hope for MDR-TB patients globally.

Till 2014, almost one in two MDR-TB patients in South Africa were not successfully treated, according to a retrospective study of 19,000 patients published in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine journal in July 2018. Two out of 10 MDR-TB patients in the country died during the 18- to 24-month long treatment, the study found.

This changed as South Africa developed and implemented a number of patient-centric initiatives that eased treatment for drug-resistant TB and made South Africa a leading example of successful drug-resistant TB care.

To understand South Africa’s successes in fighting drug-resistant TB, IndiaSpend interviewed government officials, physicians, drug-resistant TB patients and advocacy groups in South Africa. We found political commitment backed with evidence-based policies helped South Africa reduce deaths among patients and become a role-model for other high drug-resistant TB burden countries like India.

In the first part of this series, IndiaSpend reported how no more than 2.2% of India’s drug-resistant TB patients had received bedaquiline till November 2018, although India has the most drug-resistant TB patients in the world. In this second part, we compare South Africa’s policies with India’s.

Patients develop side effects of conventional drug-resistant TB medications

Phumeza Tisile is another MDR-TB patient who, like Mabandlela, developed side effects from injectable drugs. Tisile was a student at the University of Cape Town when she was diagnosed with TB in 2010. Since rapid diagnostics for detecting drug-resistant TB were not available then, she was diagnosed with MDR-TB only after conventional TB treatment didn’t work. She was then put on a regimen of 20 drugs a day, including one injection, for six months.

One night during the treatment, Tisile woke up and realised she could not hear. Side effects of the injectable MDR-TB drug kanamycin had left her deaf in both ears. “Before that, I was never counselled about any side-effects. I didn’t know TB treatment could make you deaf,” she told IndiaSpend. “When I reported my hearing loss, the nurse said she is very sorry but there was nothing that could be done,” said Tisile.

Worse, further tests revealed that Tisile had XDR-TB and was resistant to kanamycin, so she lost her hearing taking a drug that wasn’t helping her.

Student Phumeza Tisile lost her hearing as a side-effect of an injectable drug she took for MDR-TB. After recovering, Tisile has become a TB patients’ advocate, raising awareness about the side-effects of conventional MDR-TB drugs.

At the time, in 2010, XDR-TB treatment in South Africa was available only in hospitals and was aimed at controlling transmission, which entailed patients being sequestered for almost the entire two-year treatment in hospital, away from work and personal life. Tisile spent close to a year in three hospitals, including the Brooklyn Chest Hospital in Cape Town, but her health did not improve.

“Every day I saw patients around me die. There was even a separate exit for taking away the dead bodies.” She was then told the treatment wasn’t working and she was referred to MSF, which provided her with linezolid. This anti-bacterial medicine is used as a drug of last resort for MDR-TB and XDR-TB patients, but was not available in South Africa’s NTCP. While linezolid can have serious side-effects too, including blurred vision, numbness in feet and anaemia, Tisile’s health slowly improved and she was declared cured in 2013.

While her treatment was underway, she began blogging on MSF’s website in 2013, raising awareness about the side-effects of injectable TB drugs, and gained the attention of media and other patients. “I got messages from patients saying they wanted to commit suicide, that there was no hope,” she said, “I told them it will work out and they will get better.” Tisile managed to raise resources to get cochlear implants in both ears, and regained her hearing. She also restarted her studies.

Faced with poor treatment success rates till 2013, South Africa introduces bedaquiline

South Africa has 322,000 TB patients, of whom 14,000 are rifampicin-resistant (RR)/ MDR-TB cases, and 192,000 (59%) also have Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV+), according to the World Health Organization’s Global Tuberculosis Report (GTR) 2018. South Africa has 2.5% (14,000) of all drug-resistant TB patients. The success rate of MDR-TB treatment in South Africa was 54% and the death rate was 20%, till 2015, according to the Lancet study. For XDR-TB patients, the success rate was 15% and death rate was 42%.

While the absolute numbers of patients isn’t that high, South Africa’s incidence rate of 567 per 100,000 for TB cases is the highest among Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa--the five partnering emerging economies collectively known by the acronym BRICS--according to GTR 2018. South Africa is second only to Russia in incidence of RR/MDR-TB, at 25 per 100,000. The incidence rate for HIV+TB patients is 345 per 100,000 in South Africa.

| TB Incidence In BRICS Countries, 2017 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | TB cases | RR/MDR TB cases | TB deaths | TB incidence (TB patients per 100,000) | RR/MDR TB incidence |

| India | 27,40,000 | 1,35,000 | 4,21,000 | 204 | 10 |

| South Africa | 3,22,000 | 14,000 | 78,000 | 567 | 25 |

| China | 8,89,000 | 73,000 | 38,800 | 63 | 5.2 |

| Brazil | 91,000 | 2400 | 7000 | 44 | 1.2 |

| Russia | 86,000 | 56,000 | 11,700 | 60 | 39 |

Source:World Health Organization, Global Tuberculosis report 2018

Faced with such poor results from conventional treatment, South Africa included new drug bedaquiline in the NTCP treatment regimen for pre-XDR and XDR-TB patients under a bedaquiline access programme in 2013. The programme made use of 200 courses of bedaquiline that had been donated to South Africa.

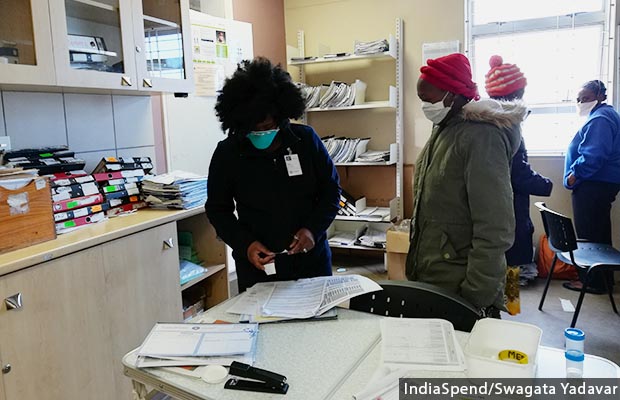

A nurse gives medication to a drug-resistant TB patient at a government health centre in Khayelitsha. In June 2018, South Africa became the first country to make new TB drug bedaquiline part of its treatment regimen for MDR-TB and XDR-TB patients.

“We used bedaquiline because we had very poor results (with earlier MDR-TB and XDR-TB treatments) and we used it in a controlled way, slowly scaling up (the number of patients). We saw that it works for us,” Norbert Ndjeka, director, NTCP, told IndiaSpend.

South Africa’s bet paid off. The results for the first 200 patients given the drug from 2012 to 2015 were encouraging--death rates plummeted from 50% to 12.5%, according to the department of health.

Norbert Ndjeka, director of the South African department of health’s National TB Control Programme said South Africa tried bedaquiline when conventional MDR-TB treatment showed poor results, and saw that the drug worked. “Other national programmes should also give it (bedaquiline) a chance,” said Ndjeka.

Patients and advocacy groups began asking why the drug (bedaquiline) that has improved mortality for XDR-TB patients was being denied to MDR-TB patients, and it became a matter of human rights, said Ndjeka.

The results gave South Africa the confidence to scale up. Since March 2015, bedaquiline has been used in the NTCP for all patients with resistance to second-line TB drugs or toxicity to the standard regime.

South Africa extends use of bedaquiline for both XDR- and MDR-TB; the WHO follows

The retrospective study of 19,000 patients treated from 2014 to 2016, published in the Lancet in July 2018, also found that drug-resistant TB patients undergoing bedaquiline treatment regimens had a much lower risk of death than those undergoing the standard regimen. This became clear when they matched data of patients with rifampicin-resistance from South Africa’s Electronic Drug Resistant Tuberculosis Register (EDRweb) and mortality data from the national vital statistics register. The study also showed a halved death rate for patients receiving bedaquiline (13%), compared to the death rate of those in standard MDR-TB care (25%). For XDR-TB, the mortality rate was almost a third--15%--among patients in the bedaquiline group and 40% in the standard regimen group.

In June 2018, South Africa became the first country to make bedaquiline part of its treatment regimen for both MDR-TB and XDR-TB patients. The new, entirely oral medication regimen replaced toxic injectable drugs with severe side-effects, including hearing loss, kidney failure and psychosis, as IndiaSpend reported in August 2018.

The decision was immediately hailed by experts and civil society. “South Africa's leadership in rolling out novel tuberculosis therapeutics should stand as an inspiration for all of us who aim to end tuberculosis, which will only be possible if innovation is embraced,” wrote Anja Reuter, head of MSF’s MDR-TB clinic in Khayelitsha and member of South Africa’s national clinical advisory committee, in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine in July 2018.

Till August 2018, 16,800 MDR-TB and XDR-TB patients in South Africa had received bedaquiline, two thirds of the global uptake of the drug, according to the Global Drug-Resistant TB Initiative.

“The approach that South Africa used was to put out the strongest drugs,” Reuter told IndiaSpend, so that transmission is first reduced, then incidence, mortality and morbidity is decreased.

“The approach that South Africa used was to put out the strongest drugs,” so that transmission, incidence, mortality and morbidity is decreased, said Anja Reuter, head of MSF’s MDR-TB clinic in Khayelitsha.

Two months after South Africa, in August 2018, the WHO recommended bedaquiline as a front-line medicine for all drug-resistant TB patients, and called for prioritising a fully oral regimen. The WHO finalised these guidelines, based on several research studies including South Africa’s experience, on December 21, 2018.

The rest of the world doesn’t have to start from scratch and can implement these lessons from South Africa. With WHO’s recent recommendations of bedaquiline as a front-line medicine against drug-resistant TB, the safety and efficacy concerns are already allayed. “We are calling on India, China, Russia, Brazil and any country with a high MDR-TB burden to start rolling out the drug,” said Ndjeka. He added that none of these countries have an 80-90% success rate, something that the drug can help achieve.

India currently makes bedaquiline and delamanid available only through a limited number of government-run centres to pre-XDR and XDR-TB patients who fit strict eligibility criteria. The government strictly controls access to these drugs amid fears of patients developing resistance to the drugs. An IndiaSpend investigation also found that India may not have adequate stocks of the drugs.

“Half a million people are diagnosed with drug-resistant TB every year. There is clearly a crisis right now and to withhold a very effective drug in the face of the crisis for an unidentified future population is very ethically questionable,” said Reuter.

Lessons from the fight against HIV helped South Africa draft a proactive TB policy

Of South Africa’s 57.7 million people, 7.5 million--or 13.1%--are HIV positive. South Africa currently has the largest national anti-retro viral treatment programme (ART; medications used to treat HIV), which provided ART to over 4.5 million HIV+ patients in 2018, but faced many challenges along the way to setting it up.

The country was plagued with leaders who misguided the public with statements saying HIV doesn’t cause AIDS, and with a national policy that did not provide the life-saving ART drugs which were deemed too expensive. Things finally began looking up in 2003, but the uptake of ARTs was still too slow, leading to large-scale protests by patients and human rights groups.

Civil society organisations such as Treatment Action Coalition played an important role in building public pressure against barriers to HIV treatment. This momentum raised by the civil society coalition also helped highlight the issues around TB treatment, and could well be responsible for the proactive role played by the South African government.

One person credited with a lot of the changes in South Africa’s policies is Pakishe Aaron Motsoaledi, South Africa’s minister of health since 2009. During his term, large scale HIV screening and treatment was made available across the country and South Africa saw a decline in AIDS deaths and cases.

Motsoaledi also served as a chairman of the Stop-TB Partnership board, formed under the United Nations (UN) to implement TB programmes. Under his leadership, many TB initiatives were implemented--such as roll-out of the Cartridge Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (widely called Gene Xpert test) as an initial diagnosis for TB, adoption of urinary lipoarabinomannan (LAM) tests to quickly screen HIV+ patients for TB, and introduction of an injectable-free drug-resistant TB regimen.

Motsoaledi also mobilised political interest in TB internationally by urging the UN to host a high-level meeting on TB in New York in September 2018, so that the disease could be debated by heads of state. It was only the fifth occasion in UN history that such a meeting was held on a health issue.

In July 2018, South Africa also took a “courageous” decision and ‘broke its silence’ over the text of a draft UN political declaration on TB that heavily diluted previous UN declarations and ‘flexibilities’ on health and access to medicines. The flexibilities were related to separating the cost of drugs from the cost incurred on their research and development. It was due to these flexibilities that ART prices had fallen by 96% since 2000, enabling South Africa to create perhaps the largest ART programme in the world. The final policy document did not dilute the trade flexibilities.

After using its initial 200 donated courses of bedaquiline, South Africa decided to procure the drug directly from its makers, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, rather than remain dependant on donations like other countries, including India. In July 2018, South Africa negotiated with Janssen to reduce the price of a six-month bedaquiline course from $750 (Rs 52,550) to $400 (Rs 28,029). This not only helped save $36 million (Rs 252 crore) for the South African government, it also made the drug accessible for other countries.

In October 2018, Motsoaledi was awarded the 2018 Kochon Prize for “Outstanding leadership to end TB”.

When presented with a new drug, South Africa gathered evidence and then found ways to give it to more and more drug-resistant TB patients. They started using bedaquiline in 2013 and over the past five years developed capacity in doctors and nurses to prescribe bedaquiline because it saves lives.

“Bedaquiline is far easier to treat drug-resistant TB with than injectable drugs, and more easily tolerated. Other national programmes must give it [bedaquiline] a chance because any new intervention must be given a chance,” said Ndjeka to IndiaSpend.

Several initiatives helped South Africa implement its innovative policies and become a world leader in fighting drug-resistant TB.

Decentralisation of treatment: After the policy of keeping MDR-TB patients hospitalised for the duration of their treatment showed poor results, drug-resistant TB therapy has been decentralised.

Each district in South Africa’s nine provinces has a drug-resistant TB treatment site with trained doctors, nurses and clinic practitioners, pharmacy and laboratory facilities. These centres also have facilities for ECG tests and audiometry to test hearing.

NTCP director Ndjeka informed IndiaSpend that 86% of the total 253 sub-district centres in the country have begun bedaquiline treatment.

To help doctors in these centres familiarise themselves with the new drug, doctors who found patients eligible for bedaquiline filled in a form and sent it to the national clinical advisory committee. These experts advised them on which treatment regimen to use. This worked well as doctors could directly discuss patients with the foremost experts in the country. After 2015, these centres did not need much more hand-holding by experts.

Each province uses social media and a WhatsApp group of primary physicians and chest physicians to get a direct expert opinion on complicated cases. This has scaled up usage of bedaquiline, said Ndjeka.

Identification and treatment: South Africa also detected populations including mining industry workers, inmates of correctional facilities such as prisons and six districts as vulnerable to TB, and developed a strategy to screen them for the disease. While mining companies were told to conduct screenings for their workers, all prisoners were then tested four times--when entering and leaving correctional facilities and twice while inside.

TB Think Tank: To get technical advice suited for its own population in a timely way, the NTCP set up a think tank in 2014. The TB think tank, as it was called, comprised researchers, government officials and members of civil society. It had three working groups for modernising TB response, delivery and implementation and new drugs and diagnostics.

Since then, the think tank has issued guidance such as securing domestic funding of $27 million (Rs 189 crore) for TB treatment, recommending a preventive strategy of using isoniazid for nine months to treat latent TB, and using a short-course bedaquiline treatment (9 months vs 24 months) for MDR-TB, among others.

Clinical Trials: South African patients have also been part of a number of clinical trials including NiX Trial, which covered all oral drugs including bedaquiline, pretomanid and linezolid for 6-9 months for XDR-TB patients; EndTB trial by MSF at Khayelitsha, which also included all oral and short regimens with bedaquiline and delamanid; and STREAM 2 trial, which had to be discontinued because it still involved injectable drugs which are no longer used in the country.

Testing for bedaquiline resistance: South Africa has shown foresight in beginning a bedaquiline resistance surveillance programme that collects routine samples of patients started on bedaquiline from various sites and tests them for resistance. A study published by researchers at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) and the department of health defined the criteria used during the surveillance for detecting resistance to bedaquiline. These criteria became part of the WHO’s policy guidance for laboratories across the world.

The surveillance has found that less than 1% of patients showed genetic markers for resistance to bedaquiline. While resistance observed during the surveillance is a cause for concern, it is not surprising since the patients surveilled were primarily XDR-TB patients, with few effective drugs left for treatment. “Ideally, you need 3-5 drugs to fight the disease and prevent resistance. We observed that patients on a sub-optimal regimen with only 1 or 2 effective drugs along with bedaquiline were more likely to develop bedaquiline resistance,” said Nazir Ismail, head of the centre for tuberculosis at NICD.

With the wider use of bedaquiline to treat all MDR-TB patients in the national programme, the risk of bedaquiline resistance will be lower as long as adherence is good, said Ismail.

Series concluded. You can read the first part here.

(Yadavar is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

Yadavar was the 2018 MSF Media Fellow. MSF has no oversight or editorial control over the final report.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.