Exclusionary Policies Push Migrants To Cities’ Peripheries

Mumbai: Migrant-unfriendly policies, social discrimination, poor city planning, and high costs of living push over half of interstate migrants to the urban fringes of India’s six largest urban centres, according to an analysis of the latest countrywide migration data from the 2011 Census.

Migrants often provide essential services in cities, working as drivers, gardeners, and domestic help, boosting cities’ economies. Yet, of a migrant population of 62.6 million in Mumbai, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Chennai, Bengaluru and Delhi in 2011, 33.4 million went to the urban fringes, found the analysis by India Migration Now, a Mumbai-based nonprofit.

These urban fringes have limited civic infrastructure and municipal facilities, prevent migrants from accessing all the opportunities of the main city, and make them susceptible to poor health and living conditions.

Internal migration, both within a state and across states in India, improves households’ socioeconomic status, and benefits both the region that people migrate to and where they migrate from, as IndiaSpend reported in August 2019. Remittances can help reduce poverty in the migrants’ places of origin.

Migration of socio-economically backward people to cities is one of the best ways of promoting inclusive development by providing infrastructure in city centres at lower costs, generating employment, and facilitating the movement of the population from remote and inaccessible areas.

Yet, interstate migration in India is less than in other countries at a similar stage of economic development, studies show. A 2016 World Bank study attributed this partly to the migrant-unfriendly policies in many parts of the country, which also force migrants to the outskirts of cities.

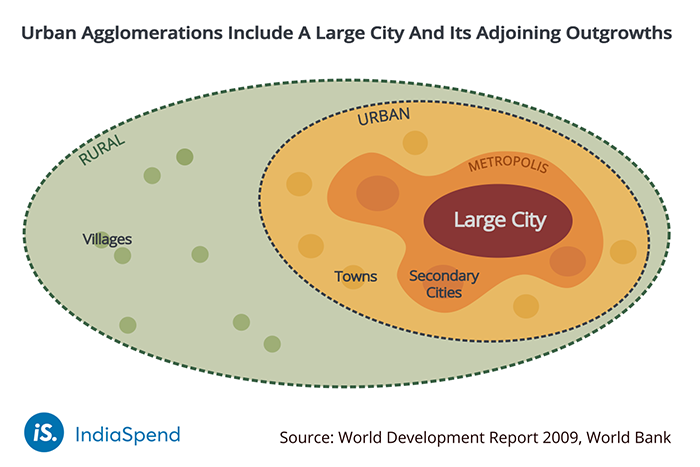

Urban agglomerations

Urban agglomerations such as Mumbai and Delhi include a continuous urban spread of a town and its adjoining outgrowths--such as Central Railway Colony in Mumbai--or, two or more physically contiguous towns--such as Noida in the case of Delhi--according to the Census.

India’s urban agglomerations often spread over several districts, have a population above 7 million, cover various municipal corporations, and have an urban core and an urban periphery (peri-urban area).

The India Migration Now analysis categorised areas as urban and peri-urban based on distance to the urban core, population, presence of a municipal corporation, the proportion of workers engaged in non-agricultural activities and the nature of urbanisation of the area, based on the 2011 census.

For example, in the Kolkata Metropolitan Area, the districts of Kolkata and Howrah were categorised as urban cores as they have municipal corporations, high percentages of built-up area and low rural populations. The districts of North 24 Parganas, South 24 Parganas, Nadia, and Hugli, with low percentages of built-up area, high rural population and no municipal corporation, were categorised as peri-urban.

Saturated cities

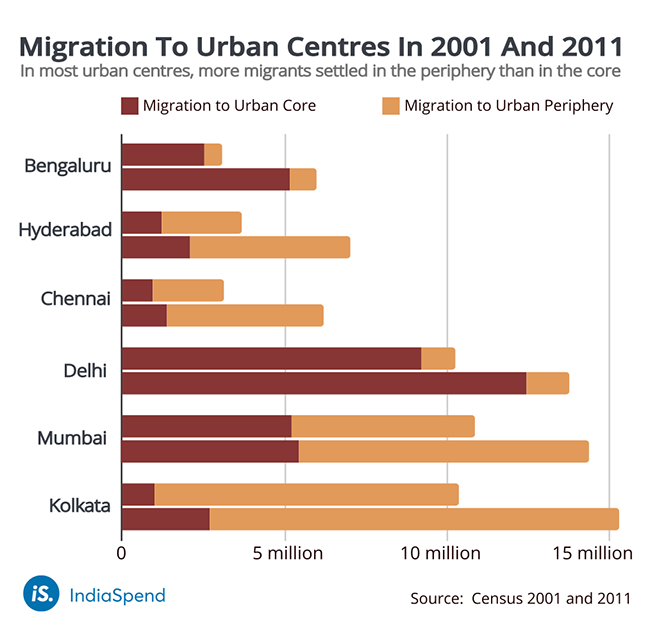

In 2001 and 2011, the proportion of migrants who settled in the urban periphery versus those who settled in the urban core was greater for the urban agglomerations of Hyderabad, Chennai, Kolkata and Mumbai.

In only two urban agglomerations, Delhi (12.5 million in the city, 1.3 million peri-urban) and Bengaluru (5.1 million in the city and 859,030 in the outskirts), did more migrants settle in the urban core, rather than the peri-urban.

The Bengaluru urban agglomeration is a relatively nascent phenomenon, and has only recently spilled beyond Bengaluru Urban into the Bengaluru Rural and Ramanagara districts. This could explain why the city is yet to reach its saturation point in terms of attracting migrants.

The National Capital Region (NCR) includes the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi as well as 23 other towns in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan, as per the NCR Planning Board. In this analysis, the Delhi urban agglomeration includes only the NCT of Delhi and its immediately bordering districts. Movement from NCT of Delhi itself to various urban hubs (Gurugram, Ghaziabad, Gautam Budhh Nagar) of NCR accounts for 6.3% (783,474) of the migration into the urban parts of NCR.

Migration to Mumbai’s core stayed mostly constant between 2001 and 2011 (going from 5.2 million to 5.5 million), but migration to its peri-urban areas increased from 5.6 million in 2001 to 8.9 million in 2011. For no other urban agglomeration did migration to the core city increase so little over the decade.

Mumbai’s massive growth and urbanisation has been driven by migration since the 1800s, according to the 2009 Mumbai Human Development Report by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. In recent years, however, the landmass-to-population ratio has been inching towards tipping point in the main city, leading to growing slums and overcrowding, the report said.

Source: India Migration Now

This dashboard by India Migration Now shows migration into the urban and peri-urban areas of Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Chennai and Bengaluru in 2001 and 2011.

Discrimination against migrants

One of the reasons driving more and more migrants (and some locals) to the peri-urban areas is the cost of living in the urban core, especially of housing, according to a 2019 paper by the Observer Research Foundation, a Delhi-based public policy think-tank.

In addition to the high cost of living, government schemes for temporary and permanent housing exclude interstate migrants, according to the Interstate Migrant Policy Index 2019 (IMPEX 2019) by India Migration Now, which analyses state-level policies for the integration of out-of-state migrants.

Migrants often stay in slums and temporary habitations, and forced evictions without rehabilitation, compensation or notice push them to the fringes.

For instance, a tussle over prime city property and the perception that the urban poor are illegal and encroach upon land prompted state response in the form of large-scale “city beautification” drives and slum rehabilitation projects, according to this 2018 report by the Human Rights Law Network, a Delhi-based legal aid organisation. Evictions took place in major cities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Bengaluru and Hyderabad.

Caste- and religion-based residential segregation, often connected to migratory status, also forces migrants to move to the peri-urban areas where the price of exclusion is at least lower, found a study published in the Economic and Political Weekly in 2012, and a 2018 working paper by the Indian Institute of Management, Bengaluru.

Migration trends among Muslims and Hindu Dalit (historically disadvantaged communities believed to be ‘lower’ castes) communities reveals diminishing access to urban space, because of several factors such as discrimination by housing societies, according to a 2019 analysis published in the journal Area Development and Policy.

Governments of several large states have had anti-migrant policies, through domicile reservation in employment, education and service delivery. For instance, the Andhra Pradesh (AP) government passed the AP Employment of Local Candidates in Industries/Factories Bill in July 2019 reserving 75% of private industrial jobs for locals.

In Maharashtra, where 80% of non-supervisory jobs and 50% of supervisory ones are reserved for state residents since 2008, the governing Bharatiya Janata Party-Shiv Sena alliance announced the possibility of a law monitoring better implementation of the quotas and extension of the law to contract-based jobs, according to this report in The Times of India published in August 2019.

The Aam Aadmi Party in Delhi wrote in its manifesto for the 2019 elections that it would reserve 85% of jobs for locals. The Karnataka government said it would implement 100% domicile reservation in private companies, according to a report in The Times of India in February 2019. All these states are home to many migrants who live and work in the periphery of their urban agglomerations.

Unequal access to health, sanitation

Migrants have inadequate access to health facilities with regard to state-level health schemes, and central government health programmes implemented by state governments--which do not account for incoming migrants--found the 2019 IMPEX analysis.

Internal female migrants in Mumbai made lesser use of health facilities for childbirth, with less than a third receiving antenatal care, according to a 2016 study.

Migrant families are also the most vulnerable and nutritionally insecure because of lack of subsidised food, and children are the worst affected due to the unavailability of the government’s Integrated Child Development Services available to them, found a 2019 study of migrants at a construction site in Ahmedabad.

Access to infrastructural services--water supply, waste management, sanitation and transport facilities--reduces as one moves away from the urban core, according to a 2013 report by the World Bank. Those living in the peripheries bear the ecological, psychological and economic fallout of this lack of infrastructure.

For example, in Bengaluru, access to network services such as piped water is concentrated in the core with access levels rapidly dropping off toward the periphery, the report said.

“In Hyderabad, despite peri-urban areas being richer in water resources, the residents of these areas lose out to a wealthier urban core population with higher purchasing power when it comes to water access,” according to a research study by the South Asia Consortium for Interdisciplinary Water Resources Studies, a policy research institute based in Hyderabad.

Similar issues exist in the peri-urban areas of Chennai, particularly with regard to solid waste management, groundwater depletion and salinity, according to a 2014 study conducted by the United States East-West Centre, a non-profit based in Hawaii, USA.

Policing and traffic administration is also poor in peri-urban areas, according to a 2019 report by the Observer Research Foundation.

Neglected peri-urban areas

In peri-urban areas, which are largely neglected by both the urban and rural administrations, there is often confusion about who is responsible for public services: the panchayat or the municipal government, found a 2015 paper published in the International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology.

Master plans for Indian cities often legitimise the peripheries, but leave them unregulated, according to a 2018 working paper by Mrinalini Goswami of the Institute of Social and Economic Change in Bengaluru. One of the reasons for this is the lack of congruence between urban planning and the realities of local governance.

For example, under the 1985 Model Regional and Town Planning and Development Law, the elected officials of the Metropolitan Planning Committees (MPC) should draw up regional development plans for urban areas. The 74th Amendment to the Constitution mandates that at least two-thirds of the MPC should be elected or should have elected members of the municipalities and panchayats in the area.

Yet, the unelected bureaucracy of the Bengaluru Development Authority continues to be in charge of drawing up the master plans. As a result, planning remains static and top-down, without public participation, and unable to adequately account for the dynamic way in which the peripheries of cities, and the needs of people, change. Inadequate coordination between different government bodies also impacts the delivery of services to citizens, according to a 2013 World Bank study.

Social discrimination

Often, peri-urban areas have heightened caste or religious discrimination, even as the urban core becomes more diverse.

For instance, Raigarh district, in Mumbai’s periphery, has been the site of caste-based conflict and discrimination, according to an India Today report, published in April 2019.

Similarly, in Thane district, also a part of peri-urban Mumbai, caste outweighs all other parameters for political parties when choosing candidates, according to a Times of India report published in April 2019.

Interstate migration increasing slower than it should

Between 1991 and 2011, more Indians migrated than in the decade before, data show. In 2011, 453.6 million migrated, almost 1.4 times of the 314.5 million who migrated in 2001.

Still, interstate migration in India grew slower in the past two decades, increasing 32% from 41 million in 2001 to 54 million in 2011. In comparison, it increased by 55% between 1991 and 2001, data show.

The choice of the city people move to depends on factors such as proximity to their hometown, perceived availability and accessibility of work. For example, Gulbarga, in Karnataka, is close to Maharashtra and Telangana and sends migrants to Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad and Bengaluru.

Historical migration trends, migrant networks and city infrastructure also impact the destination cities of migrants.

Many from the neighbouring states of Haryana and Uttar Pradesh migrate to Delhi, those from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar to Mumbai, and those from Rajasthan to Chennai and Kolkata, Census 2011 data show.

Need for new government policies

With migrant-unfriendly policies, it has become increasingly difficult for the poor to shift to urban centres in pursuit of survival. Only long-term inclusive policy-making which addresses the multiple exclusions faced by migrants in cities and peri-urban areas can help India capitalise on the opportunities of migration.

Provision of rental housing services, improvement of the service delivery system both in the urban and peri-urban areas, and better coordination between urban governance bodies could help urban agglomerations grow faster economically and provide more support to the migrant population.

(Mitra, Damle and Varshney are researchers at Mumbai-based nonprofit India Migration Now.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.