Dying Pomegranates And The Threat To India's New Farming

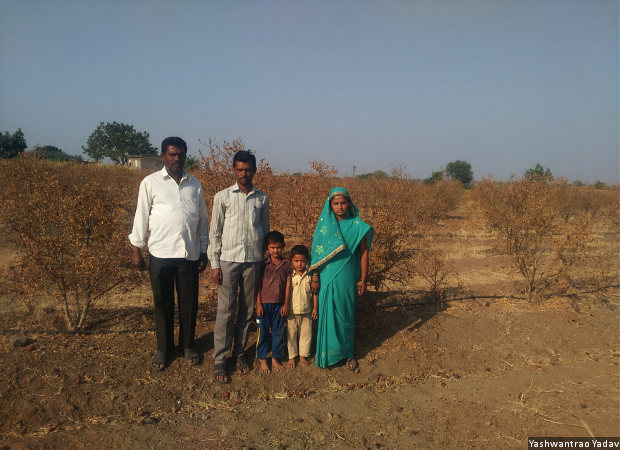

Sikandar Nazruddin Korabu with his family at his withered orchard in Karkamb village, Solarpur district, one of pomegranate-growing powerhouses that have made India the world's largest producer of the fruit. With an outstanding loan of Rs 5 lakh and a family of 14 to support, Korabu and his brother have started working as labourers on neighbouring farms.

Pandharpur taluka, Solapur district (Maharashtra): When he grew sorghum, wheat and maize on his four acres of land, Sikandar Nazruddin Korabu (50) could not help but notice how his neighbours who planted pomegranate orchards about seven years ago flourished. Their incomes had risen roughly 10 times, and some had even bought cars--a seemingly miraculous transformation here in this arid southeastern district of Maharashtra.

Korabu's pomegranate orchard represents a new, lucrative hope for Indian agriculture--fruits and vegetables. Maharashtra accounts for 80% of pomegranate production in India--the world's largest pomegranate producer--and about a quarter of that comes from Solapur district. As Korabu's experiences indicate, increasingly uncertain weather and India's slow progress on irrigation threaten these hopes.

Two years ago, Korabu--a fifth-class pass--converted an acre of his land into a pomegranate orchard. He borrowed Rs 5 lakh from a bank, Rs 2.15 lakh of which he spent on a pond, now about to run dry. His older crops depend on rain; the pomegranate orchard requires only drip irrigation, but there isn't enough water in the pond even for that. Korabu cannot afford Rs 2,500 to buy a tanker-load of water that might save his orchard.

Korabu's pond cost Rs 2.15 lakh and was used to supply water to his pomegranate orchard's drip-irrigation system. It is nearly empty, and the orchard has withered.

"All we do is work and work," said Korabu, a swarthy man given to hard work. "Nothing comes out of it." With two cows, 14 hens and remaining farmland insufficient to support the extended family of 14, all of whom live in a three-room house (including the kitchen), Korabu and his elder, illiterate brother also work as farm labour, each earning Rs 200 every day.

Korabu's water woes are full blown across Solapur district, other parts of Maharashtra and in many Indian states, currently struggling with a new season of unseasonal rain, drought and hailstorm.

In Solapur district, IndiaSpend found withered pomegranate orchards and desperate farmers using tankers to irrigate fields. Farmers plead for government help, while hundreds of tankers fanning out across rural Maharashtra are the only water source for many communities--as the photos below show.

In Kardehalli village, south Solapur, people have lined up pots and buckets for two days, waiting for a government tanker to arrive. Hundreds of villages in Maharashtra now depend on water tankers for domestic and farm needs.

Gangadhar Birajdar of Shripanhalli village, South Solapur, uses tankers to water his vineyard. His land is not irrigated and there has been no rain. Birajdar spends Rs 1,500 on each tanker, using two tankers every day over the last nine months to save his five-acre vineyard. He has spent Rs 800,000 on water tankers so far, paid for by his savings, a bank loan and his brother's salary. Saving the crop is his priority, but he has run out of money.

The uncertain weather has come at an inopportune time. Pomegranate orchards produce their best yields for a decade, and for many farmers that phase arrives next year. The new plantings call for large investments and a two-year wait for fruit.

"I humbly request the Maharashtra government and the Solapur district collector to provide us water tankers to save our perennial fruit crops, such as grape and pomegranate," said Gangadhar Birajdar, 51, a farmer who now trucks water to his field, a situation he cannot afford. He lauded the government's attempts at long-term "drought-proofing"--a programme with mixed success, as IndiaSpend reported in January 2016--but, he said: "Our gardens that have borne fruit over seven years are dying now."

Birajdar has spent Rs 800,000--his savings, a bank loan and the salary of his brother, a primary school teacher--over nine months, buying water from tankers to save his farm. When we met him, Birajdar had run out of money.

How the pomegranate changed lives and farms

Maharashtra farmers began pomegranate farming about 25 years ago, when the government promoted orchards through an employment guarantee scheme.

Before the pomegranate programme, farmers grew cereals, such as jowar (sorghum), bajra (pearl millet), maize and wheat, pulses, such as chickpea and green gram, and oilseeds (groundnut and sunflower).

Farmers worked hard--many report living in the fields to monitor progress--learned crop, fertiliser and pest management and how to access markets.

Source: Maps of India

Larger farmers moved from small homes to bungalows and bought cars. Farmers with smaller holdings or success also moved up, from shacks to homes and two-wheelers and put children through school.

In south Solapur's Boramani village, Sushilkumar Suresh Ukrande described how pomegranate allowed him to build a "pucca" (brick-and-cement) home and buy a motorcycle.

But the meteorological uncertainty of the last two years--worsened by bacterial blight and price fluctuations--have made returns uncertain and unpredictable for large, marginal and small pomegranate farmers, such as Ukrande and Korabu.

The lack of water is ravaging farms across what is called the pomegranate belt: Solapur, Nashik, Sangli, Satara, Pune and Ahmednagar.

"In these districts, the water shortage has been severe over the last two seasons, and in the current season, many are struggling to save their two- to seven-year-old orchards," said Prabhakar Chandane, president of the All India Pomegranate Growers' Association. "In many places, pomegranate orchards are stunted; the trees are withering, drying and dying."

The pomegranate-farming crisis illustrates how the lack of irrigation and climate change threaten India's new agricultural hope: Horticulture--which includes fruits, vegetables, plantation crops, such as tea, coffee and rubber, and spices--now surpasses foodgrain production. India is the world's second largest producer of fruits and vegetables.

Source: National Horticulture Board

How the lack of water could hold back agriculture's diversification

Irrigation is particularly important because India’s agriculture growth contracted 1% in the October to December quarter of 2015 and is predicted to grow only 1.1% in the financial year 2015-16 (advance estimate, obtained by extrapolation of latest available data). Farms have been ravaged by back-to-back droughts, the worst in 30 years; winter (rabi) crop sowing dropped below 60 million hectares, the worst in four years; and thousands of farmers nationwide have committed suicide since last year.

Of India's 138 million farmers, 66 million depend on increasingly uncertain rains. Extreme rainfall events in central India, the core of the monsoon system, are increasing and moderate rainfall is decreasing–as a part of complex changes in local and world weather, as IndiaSpend has reported.

With no end in sight to the farm crisis, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley announced in February that the government would spend Rs 86,500 crore ($12.7 billion) over the next five years to irrigate 80 million hectare of cultivated land. This means the government is promising to irrigate in five years more land than it has in the 69 years since Independence, and, as IndiaSpend reported last week, the irrigation programme that Jaitley is investing in is failing.

Only 65 million of 140 million hectare, or 46%, of Indian farmland is irrigated, according to Agriculture statistics released in 2014. The World Bank, however, reports no more than 36% of farmland is irrigated.

Maharashtra’s experience with irrigation has not been promising, with the state’s irrigation potential—the area that can theoretically, or potentially, be irrigated with new facilities—increasing by no more than 0.1% despite spending Rs 70,000 crore, roughly since the turn of the century, as this Business Standard report noted, quoting the state’s own economic survey.

The lack of irrigation evident in Solapur district is as evident in neighbouring Marathwada, parts of which face a worse farm-and-water crisis; as IndiaSpend reported in January, parts of Marathwada are living through a drought that equals the worst in a century.

For now, Solapur's farmers request "urgent" short-term measures, such as subsidy for mulching paper--which slows evaporation and retains moisture in the soil--for their orchards, tankers and a reorganisation of a farm-pond programme called Magel tyala shet tale (Ask and you will get a farm pond). The present grant of Rs 50,000 is not enough for the ponds they need, because summer has increased rates at which water evaporates or seeps into the ground.

In the long-term, though, only modern irrigation, concerted government action and close agricultural-extension support can help Korabu and the other pomegranate farmers of Maharashtra.

(Yadav is a doctoral scholar at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.