Clean Air Could Increase Life Expectancy of Indians By 1.7 Years

New Delhi: If Indians had cleaner air to breathe, their average life expectancy would increase by 1.7 years, from the current 69 years to 70.7, a new study has said.

Air pollution caused one in every eight deaths and a total of 1.24 million deaths in India in 2017. More than half these victims were less than 70 years old, according to the air pollution mortality and morbidity estimates by India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative published in The Lancet Planetary Health on December 6, 2018.

India’s annual average level of fine inhalable particles in the air, commonly referred to as PM 2.5, was 90 μg/m3--the fourth highest in the world and more than twice the limit of 40 μg/m³ recommended by the National Ambient Air Quality Standards in India and nine times the World Health Organization annual limit of 10 μg/m3.

India has a disproportionately high share of premature deaths due to air pollution--despite being home to 18% of global population, it accounts for 26% premature deaths and disease burden due to air pollution.

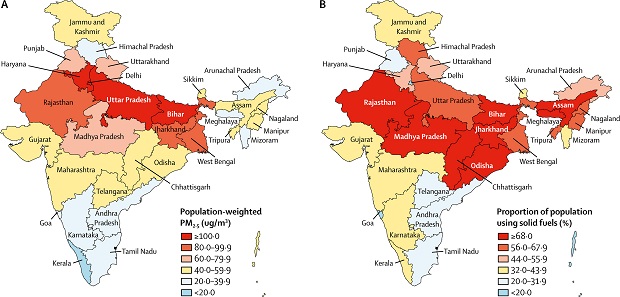

About 77% of India’s population was found to be exposed to ambient air pollution levels above the national safe limit. Worst-hit northern states include less-developed ones--Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar--and affluent ones such as Delhi, Punjab, Haryana and Uttarakhand.

“There was skepticism in India regarding the estimates of ill health due to air pollution but this study proves that air pollution--including both ambient and household pollution--is one of the biggest risk factors for death and disability in India, more than tobacco use, salt intake, high blood pressure and any other risk factor,” Kalpana Balakrishnan, professor, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai and lead author of the study, told IndiaSpend.

“This study conclusively proves that air pollution leads to a decrease of 1.7 years of life expectancy and not four years as believed before,” said Balrama Bhargav, Director General, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).

The study was the first ever comprehensive estimate of impact of air pollution in each state of India and was jointly conducted by the ICMR, the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). The initiative works in collaboration with the ministry of health and family welfare and over 40 experts across India.

Poor, less developed states have earlier deaths

As pointed out earlier, 77% of the country was exposed to annual mean PM 2.5 levels higher than the national limit and there was significant variation between pollution levels in different states. The state with the highest ambient air pollution was 12 times worse than the state that suffered the least. This difference was 43 times in the case of household pollution.

The minimum exposure level of PM 2.5 is between 2.5 and 5.9 μg/m3, said the report.

Northern states with lower social development index (SDI)--calculated using per capita income, education levels and total fertility rate--Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Jharkhand had the highest levels of both ambient and household pollution. These states would benefit the most if air pollution was lesser: For example, inhabitants of Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh will add two more years to their life if air pollution was below the national limit.

Badly affected middle and high SDI states such as Delhi, Punjab and Haryana could also add to the life expectancy of their residents from the reduction of ambient air pollution but by fewer years--1.6, 1.8 and 2.1 years respectively.

Source: The Lancet Planetary Health

Solid fuels lead to high deaths and disability

Even though more than half (55.5%) of the country is still using solid fuels--dung, coal, wood and agricultural residue--for burning, it was greater than 72.1% in the low-SDI states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. These states together suffered half the deaths caused by household pollution.

Source: The Lancet Planetary Health

All states had deaths attributed to household pollution. For example, Kerala has almost equal number of deaths due to ambient and household pollution. “It is a myth that most states have shifted from solid fuel to cleaner fuels,” said Balakrishnan.

There has been a 30% decrease in household pollution in the last five years (2012-2017) but it is too early to say if it is due to Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) that aims to distribute LPG cylinders to low income households, said Balakrishnan.

While it has the potential to cause single highest decrease in household pollution, evidence will be available two years from now. “While the problem of access and availability of clean fuel has been solved, the focus should now be to make it affordable,” she said.

Household air pollution led to 482,000 deaths and 21.3 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs)--years lost due to ill-health, disability or early death--in 2017.

Ambient air pollution affected 38.3% more men than women while household pollution killed 17.6% more women than men.

More respiratory issues due to the air than smoking

Air pollution is commonly associated with lung disease but contributed to 38% of India’s cardiovascular disease and diabetes burden in 2017.

In 2015, 2.5 million of 10.3 million deaths in India due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are linked to pollution. This makes India the country with the highest number number of pollution-related deaths, followed by China, IndiaSpend reported on January 3, 2018.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) led to 13% of all deaths and 7.5 million were at risk of the disease in 2016, IndiaSpend reported in January 2018.

Since PM 2.5 crosses the blood-air barrier affecting all organs of the body, the government is taking serious cognisance of its health impact and has included COPD in its screening programme for non-communicable diseases as part of Ayushman Bharat, said Bhargava of the ICMR.

The disease burden for lower respiratory infections due to air pollution was higher than the rate attributable to tobacco use.

For non-communicable diseases, including COPD, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes, lung cancer, and cataract, disease burden due to air pollution was same as that of tobacco use, said the report.

State-specific strategies suggested

“Control of ambient particulate matter pollution requires action in several sectors and the linkage of these actions for greatest impact,” said the report.

The report suggested state-specific policies--in Delhi, the use of compressed natural gas by vehicles; in Punjab, subsidies for alternative technologies to compost agricultural waste so it does not have to be burnt; and in Maharashtra, the mandatory use of fly ash in the construction industry within 100 km of coal or lignite thermal plants. But these measures can also be expanded to other states with particulate matter emission issues, it said.

The Clean Air for Delhi Campaign, launched in early 2018 by ministry of environment, forest and climate change, that led to the launch of the National Clean Air Programme got a special mention in the report. The programme aims to sensitise the public on issues relating to air pollution and enhance coordination between the implementing agencies across the country.

The report was also optimistic about the impact of efforts like India’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution target--that countries take themselves to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change. India’s target aimed at the reduction of particulate matter by 33-35% by 2030.

The promotion of electricity-driven public transport and upgradation of vehicles to the emissions-friendly Bharat Stage VI standards will also help reduce pollution levels, the study said.

(Yadavar is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.