Centre Must Give States More Money Or Let Them Borrow: Kerala Finance Min Thomas Isaac

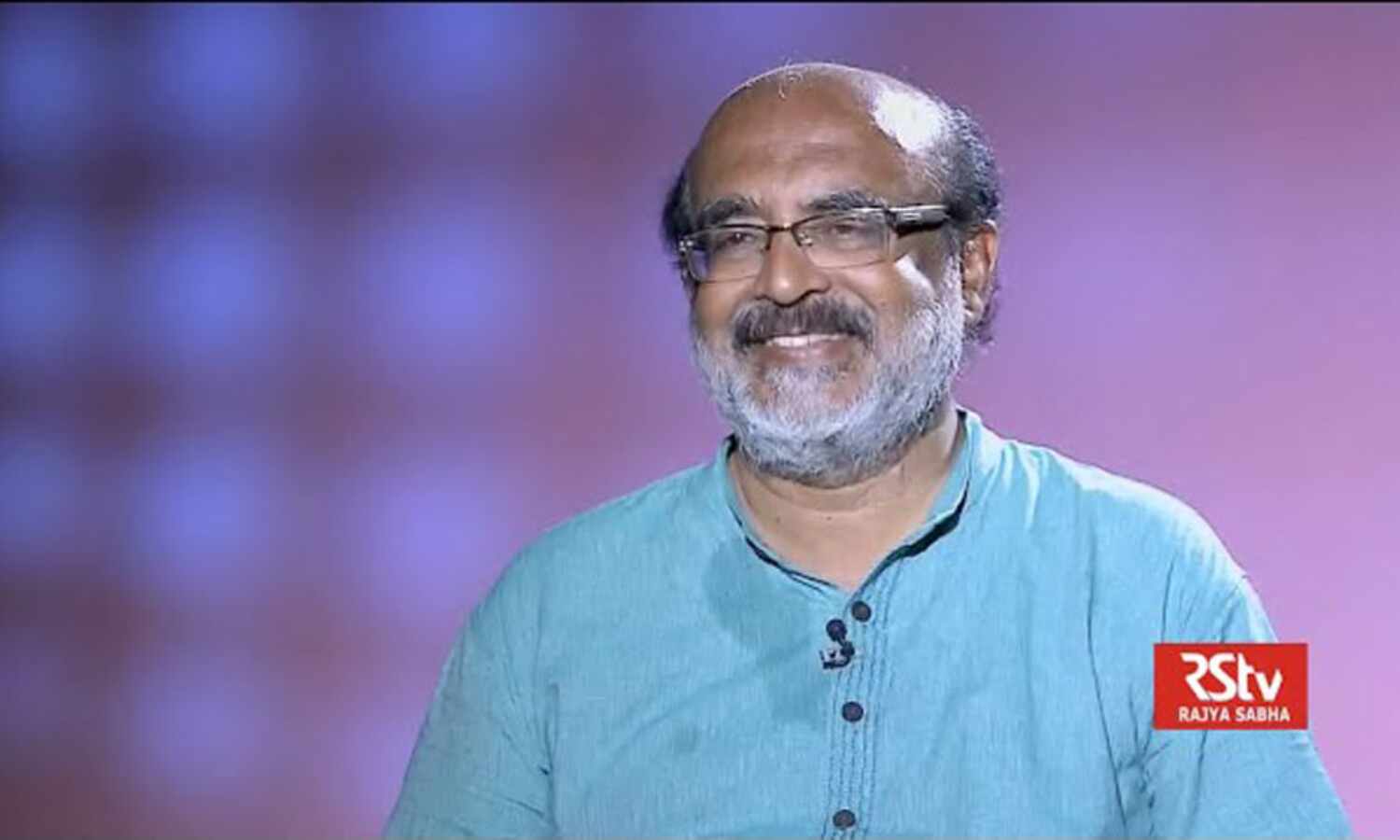

Mumbai: Kerala claims it is financially broke. Earlier, the state said it wanted money and not appreciation for fighting COVID-19. It now has just about 500 cases, and has reported no new cases on May 4 and 5. What is the way out, and forward, as India and Kerala get back on their feet and back to work? We speak to Kerala’s Minister of Finance, T.M. Thomas Issac.

Kerala says it is broke. But so are many other states in the country. So, why should Kerala be given a priority?

Why should I be given help, support? That is what a federal government is about. The resources are mostly in the hands of the Centre, but responsibilities are more on the shoulders and in the hands of state governments and therefore, there is already a constitutional mechanism for transferring funds. That is in the normal time. Now, you have an extraordinary situation, where the normal income of the state governments has disappeared; the Centre is also in hardship, but it has the right to create new money. And that is what, all over the globe, governments are doing--the US has made available something like 10% of its GDP [gross domestic product] in additional money. This is broadly the situation in all developed countries.

The Indian government can just directly borrow from the Reserve Bank and make money available to the states also. Otherwise how do you fight the “war”? See, this manner of Government of India’s behaviour makes me suspect that they want to put the entire burden of the pandemic on the shoulders of the people and the states. And they may have some macroeconomic vision about that--how in the post-COVID world, they would be good and strong. But suppose there is no economy at the end of the pandemic times, what are you going to do?

My question also is: almost every state is now in the same boat. Your GST collection numbers stood at Rs 1,800-1,900 crore in April 2019. Now you are at about Rs 153 crore. Proportionately, that would be the case of almost every other state, and some states may be worse than you. So how does the central government prioritise between states and why should Kerala be the first and not an equal recipient of what the Centre may be able to give out?

One, we have to accept that the revenue receipts of the state governments are only, say, 10% of the normal--all state governments. Now, what do we do--either the central government gives the money or permits them to borrow. Now, we tried to borrow; we front-loaded our borrowing because we were serious about fighting COVID-19. And that is what the numbers [you] said mean. We have only 34 active cases now. In a couple of days, we will go into a single digit. And that is because we have taken it seriously, it has cost money--it has not come for free. So, we front-loaded our borrowing--we had to pay 9% interest, with a repo rate of 4.4 because we asked for a large amount of Rs 6,000 crore. The Reserve Bank advised us to borrow a smaller amount, for a shorter period.

But, you know, the central government did not think twice when Mutual Funds were in trouble, they had to be helped--Rs 50,000 crore were pumped in. Don’t you think that the states have to be supported? They are bankrupt. It is a very strange behaviour which makes no sense to me.

Can you take us through the current situation in Kerala? I read that you reported an income of about Rs 250 crore, but your expenditure per month alone is Rs 3,850 crore, your salaries and pension alone come to Rs 2,500 crore--is that correct?

My salaries alone would come to Rs 2,500; pensions would be another Rs 1,000. Then last month we have spent something like, income transfer, arrears [and/in] welfare pension, Rs 1,000 to every family. So, some Rs 8,000 crore.

And then there are health expenditures. The first file of this financial year was for medical supplies, for which Rs 400 crore were budgeted. I know it is too small, we have to give something more. So on the first day of the financial year, the first file I signed was for Rs 600 crore for medical supplies—the whole year’s allocation in one day. This is the expenditure that we have to incur, but how do you meet the expenditure? That is the question.

And you have also deducted or are deducting salaries to the tune of six days a month for the next five months from government employees and that is going to save you about Rs 500 crore a month. Is that correct?

It gives us around, say Rs 2,500 c rore, which we agree to pay [back to the workers and employees] next year or the year after. We have brought an ordinance saying the government will have to say by when this money will be returned, within six months of deferring this money--the workers/employees are not donating it, they are deferring it and the government will also have to simultaneously declare that they will be repaid in this manner. So, we are very reluctant to cut any salary, we want to protect workers’ and employees' rights. But, as a matter of fact, the state government does not have the money. So, we postponed, we deferred the salaries.

Unlike other states, which are facing reverse internal migration, Kerala is facing reverse cross-border migration. Estimates say about 300,000 Malayalees will return by September 2020. What is the impact of that likely to be?

I think it will be 500,000. That is a large number and they are all coming from hotspots. Now the problem is about 100,000 would be coming back, having lost their jobs. And, of course, they are sending back relatives and family who are living there, sending them back to Kerala because they think Kerala is safe. That is good, but bringing them back immediately raises the challenge of a second wave. We have flattened the curve for now, but it [will/might] spike again. So, we want to ensure that the spike is contained within manageable limits. We are not thinking of eradicating it but within manageable limits, within the limits of the hospital facilities that we have. We do not want to have the situation where we cannot provide ICU beds for the sick. And so, we want to contain it at that level. And therefore, our strategy has been relatively cheap. If you take the number of per capita tests per 100, 1,000 or 1 million, Kerala like India is very much below the international level (though it is a little better than the national level).

You have done about 33,000 tests.

That is right, but if you take the ratio, the population ratio, internationally it is very, very low. But what stands out in the case of Kerala is that, despite this, the R0 (reproduction rate) is very low—0.4. Normally, in the initial stages it is 2, then 1. If you are above one, there is exponential growth. If you are below one, the curve will flatten over time. So, this has been achieved not just by testing but also by quarantining and observing. It is not enough to lockdown; we have to observe. Any person developing a symptom will have to be tested. And the rest of them on a random basis.

We do not have the money nor do we have the kits, there is absolute scarcity, even if you want to test, you cannot. So therefore, the thing is to observe them. Keep them under lockdown—28 days maximum and by then even if you are asymptomatic, the virus in your body would be dead. Even if you test positive, still the virus would have died in your body.

I am saying the commonsensical thing, maybe medically it has to be proved. But it is the major takeaway from Kerala. See, Kerala is very famous for its health achievements and these have been achieved at a relatively low cost. That is stunning. The health achievements of Kerala are remarkably similar to developed countries, but our per capita income is so much lower. Therefore, this is a much more sustainable way of achieving the SDG goals and so on, I would say.

So, this is what I would take from Kerala’s experience: Test, yes, have more tests. But tests alone won't do. There is no point in running around testing everybody. States must quarantine anybody with a symptom. If anybody is COVID+, trace all their contacts, quarantine them and observe them.

So, from what you are saying, given the impending reverse flow of Malayalees from the Middle East and maybe other parts of India and overseas, for which you have to be medically geared for, your focus is really health and may not be so much the economy?

No, we are going to open up our economy. That is the first step. Plus, we will quarantine all those who come from outside. Then, we will quarantine all of our vulnerable population--some 2 million people, the elderly, the vulnerable, will have to stay indoors and this lifting of the lockdown will not apply to them. The rest will go to work. These people, we manage--if they develop symptoms, they will be observed and tested, and so on and so forth.

You must learn to live with SARS CoV2--you have to observe what is happening and then be flexible; you will be moving to and fro, from green zone to red zone, and red to green. But your economy will be working at some 50%, 60% or 70%. And then you have to lay down your priorities. What are you going to unlock and activate?

We are thinking about certain priority sectors. Our health brand is good; therefore, we are going to focus on medical devices, pharmaceuticals, getting a consortium of entrepreneurs to have a Kerala-generic brand. Two, our tourism--we are going to sell our tourism as the safest place in the world. Come, you are taken care, no novel coronavirus will reach you.

It is God’s own safest country

Yes… so we have tourism, IT, then cultivation. We want to bring back vegetables, intercropping and so on. Now people are staying indoors, so let us do this--so we have a clear exit strategy. We are going to live with the novel coronavirus, we are going to open up. But the important thing is: you cannot do this unless you have a public health system. So, we will be investing in our public health system also.

In the rest of India, there is going to be a problem opening up, you are going to have a spread, and if not controlled, you will end up with the pandemic again. So, the Government of India should think of having a string of public hospitals. Convert some of the resorts into public hospitals and recruit doctors and employ them. Spend a trillion rupees, not Rs 15,000 crore. It is a shame if you think you can fight COVID-19 with Rs 15,000 crore. And that too spread over three years. What thinking is this? Anyway, we want to start…

You have had a very intense period in the last eight to 10 weeks. What is the one instance that remains in your mind and reminds you in some ways of the hope that lies ahead in our ability to fight this disease and in our faith in our own selves to survive and sustain?

The best I think in Kerala is that all the patients are leaving the hospital. And then in front of the hospital, they have a sendoff party--all the hospital health workers come out, they all clap, as these people leave. Day after day, in every hospital this is being repeated. It also tells me the kind of empathy with which our health workers took care of them. And the glorious tribute these patients pay to the hospitals. That is something that has moved me. Particularly, when I compare with the elite hospitals in India, where our Malayalee nurses complain that they do not have protection gears, they do not have medicines. Our taluk-level, small hospitals treat people better. That is something that makes me proud--what a heritage we have.

Secondly, even in Kerala the migrant workers are not treated as equals. We want that, we aspire to that. There are cooperative societies, that migrant workers are members of. But now we have been able to give them better treatment during the COVID-19 crisis. There were sendoff parties for every train--all waving to each other. That is something I felt very happy about. Nobody was thinking, good riddance. No. And I say come back, we are waiting for you. You have a job here. That is a good feeling.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.