Bundelkhand Farm Loans: Deadlier Than Home Loans

("Villages in Bundelkhand are poor, hot and dry. Farmers depend mainly on rainfall, which has been unpredictable for more than five years")

Banda (Uttar Pradesh): Almost a year ago, Congress scion Rahul Gandhi said that one of India's poorest, most suicide-prone regions at the nation's heart, Bundelkhand, had the potential to become Bangalore.

Yet, in the seven parched districts of Bundelkhand that fall in Uttar Pradesh (six fall in Madhya Pradesh), at least 3,000 farmers killed themselves over the last five years, according to official records and suicides reported in newspapers, the terms of agricultural bank loans that underlie these deaths dramatically more unfavourable than home loans given to the urban middle class in Bangalore.

For the Bundelkhand farmer, a loan of Rs 10,000-loan rises to Rs 18,704 in four years. A Rs-10,000 urban home loan rises by that amount in 15 years, according to my calculations.

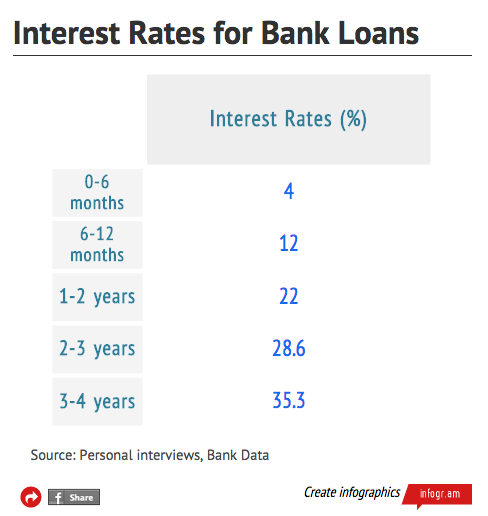

A variety of banks, including State Bank of India, Allahabad Bank and rural banks, has lent Rs 1,578 crore to farmers in Bundelkhand. For the first six months of the cropping season, the interest rate is 4% per annum, skyrocketing to 22%, if the loan remains unpaid after a year. Farmers get a loan of Rs 5,000 for every bigha (one acre is 2.5 bighas) of land.

If the loan isn't paid within the first six month, the rate rises to 12%. If it is still unpaid, banks proceed against the farmer, and once a legal case for recovery is filed, an additional 10% is levied as expenditure for "corrosive action", a term used by the Allahabad High Court. This 22% interest is compounded every six months.

An urban home loan generates an interest that varies from 10% to 12% per annum, and it does not place the kind of physical and emotional burden that Bundelkhand farmers experience, a domino of bank loans, failed crops, strong loan-recovery steps by banks--often in violation of a court order--humiliation and, ultimately, suicide.

In the seven districts of Bundelkhand in UP, 58 farmers killed themselves between January and August 2014, according to a public interest litigation filed by the All India Kisan Union in the Banda district court seeking compensation and permission to sell crops (rice, wheat, oilseeds and pulses) in the open market.

The data, from secondary sources, such as personal interviews and newspaper reports, only represent the official data for suicides by male farmers and do not include female suicides. The actual numbers are much higher, my research has shown. A number of farmer deaths have been denied as agrarian distress and attributed to either personal reasons, such as domestic issues and personal health. National Crime Records Bureau data reveal that farmer suicides are growing in both UP, which reported 750 farm suicides in 2013, and MP, which reported 1090. According to a study in the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), most of these suicides occur in the Bundelkhand region across MP and UP.

All of Bundelkhand's districts across MP and UP are on an official list of India's 200 most backward. This tribal homeland was once among's India's lushest, carpeted by forests. Now ecologically degraded, with much fertile land lost to dam projects, most of the farming depends on rain or, in Banda, on canals. Between 2004 and 2010, Bundelkhand reported below average and erratic rain. The area also saw the highest rise in indebtedness of any region in UP. The uncertain rainfall and the effects of living with this uncertainty has set off a chain of events that ends by farmers killing themselves.

The suicides in Bundelkhand have sparked numerous agitations, which political parties have exploited. On July 15, 2011, the Allahabad High Court said: “The state government, nationalised and private banks, financial institution, cooperative banks, Khadi Gramudyog Development board will not take any corrosive step to recover outstanding agriculture loans from the farmers in the Bundelkhand area”. This decision was appealed in the Supreme Court by State Bank of India and Allahabad Bank and a judgement is pending.

But banks continue to recover loans from farmers. A right-to-information (RTI) question submitted to banks in 2013 from the All India Kisan Union to banks asking how many recoveries were made since the High Court decision resulted in data from only one district but the loan-recovery admissions were apparent.

In such a situation, where farmers believe the support price for crops is not in accordance with the costs they incur, interest rates for bank loans and their recovery processes appear counter beneficial to the old system of borrowing money from local money lenders. Abandoning farming appears to be the only option, for many. More than 56,000 people have migrated from Banda district between January and August this year, according to official records quoted to me by leaders of local farmers' union. Their stories need to be told. The government needs to examine what has happened in this land, once known as the food bowl of Bundelkhand.

(Nimisha Agarwal is a Phd student researching issues related to agriculture and climate change in four district of Bundelkhand)