‘Better Staff Morale, Prisoners’ Goodwill Were Key To Telangana’s Prison Reforms’

Hyderabad: Telangana prisons have seen a turnaround: their occupancy rate dropped from 88% in 2014, when the state was carved out of undivided Andhra Pradesh, to 76.8% by 2017. Prison deaths fell from 56 in 2014 to eight in 2018. At the beginning of 2019, the state’s prisons department declared itself corruption-free.

The department set up 18 petrol pumps run by serving and released prisoners, and in 2018-19, earned a profit of Rs 20 crore, up from Rs 3 crore in 2014. Inmates could make phone calls and meet visitors more easily. Nearly 130,000 prisoners turned literate. Interest-free loans were offered to families of prisoners. After-care services were introduced to help rehabilitate released prisoners.

These reforms earned a special mention in India Justice Report, released on November 7, 2019, by Tata Trusts in collaboration with the Centre for Social Justice, an Ahmedabad-based nonprofit, Common Cause, a New Delhi-based nonprofit, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, an international nonprofit, Daksh, a Bengaluru-based civil society organisation, Prayas, a social work demonstration project of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, a New Delhi-based legal think-tank. The report ranked Telangana prisons 13th among 18 large and mid-sized states.

Keeping prison staff motivated and earning the goodwill of prisoners was key to this transformation, said Vinoy Kumar Singh, the former director general of Telangana State Prisons Department, who steered these changes during his tenure between 2014 and 2019.

Singh, 59, is a 1987-batch officer of the Indian Police Service, and currently the director of the Telangana State Police Academy in Hyderabad.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

What was the state of Telangana prisons when you took over?

The concept of prisons covers two areas: The safe and secure custody of prisoners, and secondly, their reform. But, the aspect of correctional services is missing all over India. And, almost everywhere I found that the prisons department personnel have low self-esteem. [There was] no motivation, funds crunch, overcrowding. There was a lot of dissatisfaction among the prisoners as well as the personnel.

How did you make these reforms work?

First, I decided to change the psychological climate [in the prison]. When we started the Unnati programme [a one-month behavioural skill development programme], C Beena, the retired professor and head of Psychology at Osmania University, was not welcomed by prison officials or prisoners. Later, those who did attend broke down. And there was a higher uptake through word-of-mouth communication.

This way, almost 4,000 prisoners were counselled, of whom only 27 came back [by committing a repeat offence]. We closed down 15 sub-jails because there was a dearth of prisoners. I thought, unless your people are motivated, nobody is going to receive any inputs.

In 2017, India had 611 correctional staff (welfare officers, psychologists, lawyers, social workers) for more than 450,000 prisoners across 1,412 prisons. Telangana had just one for over 5,500 prisoners. The Model Prison Manual, 2016, requires one correctional officer for every 200 prisoners and one psychologist/counsellor for every 500. Why are there such gaps?

Funds crunch is one reason. Secondly, the [lack of] awareness. I tried to plug that loophole.

Yet, there was only one correctional staff in Telangana. Why is that?

Yes, but that doesn’t make any difference because we have supplemented the efforts [with consultants, as with the Unnati programme]. And, that is more effective than having somebody on permanent rolls.

You spoke about prison staff?

Prison staff, and the goodwill of prisoners--we have to win over their goodwill. Otherwise, they will not cooperate. They are all stakeholders.

I decided that prison buildings should get in shape. Since prisoners stay there 24x7, it is in their interest [to repair them]. Jails were changed in one year. A lot of officers from outside the state--and a delegation from Bangladesh, and Sri Lankan prison officials--said it [one prison] looks like a resort.

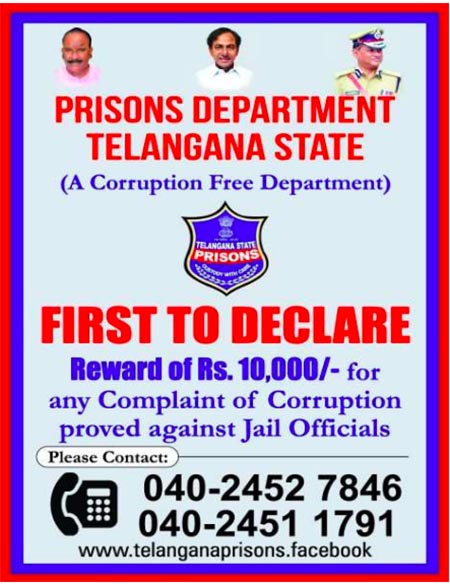

We also repaired the quarters of the prison staff. We provided vans to drop their children to school. We gave them interest-free loans, and told them not to take bribes from visitors who came to meet prisoners. I declared a Rs 10,000 reward for anybody who proves an allegation of corruption against any jail officer. This brought us tremendous goodwill from the prisoners.

We were very harsh on personnel who indulged in corruption. We suspended them, transferred them and started disciplinary action.

Did you receive any complaints?

Yes, and I gave rewards as well. But, there were very few [such instances]. Before that, we did a lot of groundwork. We had started a third-party call centre which spoke to released prisoners about their experience in the jail.

In the beginning, we used to get many inputs, and on that basis, we started taking action. So, it created fear among the corrupt personnel.

How did you earn the goodwill of the prisoners?

We improved the food. We started giving interest-free loans to prisoners. We made phone calls and meetings easier. So, the feeling that we are here, bottled up in this enclosed space--that was gone. We never found a single instance of prisoner violence in five years. Earlier, there were firings, murders, fights and jailbreaks.

Our main job is to keep the prisoners gainfully engaged. Almost all the prison industries in India are defunct. We would not get raw materials. By the time the budget comes, half the year is gone. And then, you have to return funds because you cannot use them [in the stipulated period].

When I joined, state prisons were running at around Rs 3 crore profit. And, when I left, in four years, it became almost Rs 20 crore, and this year, I think they will be clocking Rs 40 crore profit.

My idea was, by 2020, [the department] should reach self-sufficiency.

Telangana has the second highest illiteracy rate in the country. We have a captive audience, captive learners. In the last four years, we made nearly 130,000 illiterate and semi-literate people literate. And we did all this without spending a single penny.

You were talking about 15 sub-jails being closed. At 76.8%, Telangana’s prisons had among the lowest occupancy rates in the country, as of December 2017--the year for which the latest data are available. Between December 2016 and December 2017, this number saw the highest drop--from 88%. How was this achieved?

We focused on rehabilitation: We opened a chain of petrol pumps, outlets for jail products, ayurvedic spas and many such [enterprises] to be run by released prisoners. Unless you give them some means for sustenance, they will fall back into a life of crime.

I also started the concept of after-care services. Somebody should be there for released prisoners as psychological support, helping them with jobs and any problems they face with the police or their own families.

We deputed two persons in each district to list and contact all hardcore criminals. Most of them said that though we are not committing crimes, police are harassing us. In many cases, we supported them. It took time but slowly, the number of prisoners in Telangana started going down.

You mentioned petrol pumps--how many were opened?

We had started 18 pumps. I had planned to start 12 more, when the government abruptly transferred me out. My idea was to start 100 petrol pumps. We also worked as a placement agency. We used to organise job melas [fairs], and we invited many companies.

How much did the petrol pumps boost the department’s finances?

It was not only a money-earning enterprise. We wanted to rehabilitate released prisoners, and give some work to serving prisoners.

Private petrol pump owners paid Rs 7,000-8,000 a month for 12 hours’ work each day. We used to pay Rs 12,000 in rural areas and Rs 15,000 in Hyderabad each month for eight-hour shifts. Why did I pay more? I am rehabilitating them and reforming them, which will ultimately help society. They will not commit crime [again].

And it proved to be a blockbuster [initiative]--it was appreciated by everybody, particularly women prisoners.

“We hope that in the 2021 budget, the jail department will not have a need for budgetary allocations,” you told the press in February 2018. The prison department was allocated, on average, Rs 112 crore a year between 2014-15 to 2017-18. You mentioned these industries, but what were the steps taken that increased profits from Rs 20 crore to about Rs 100 crore?

First, I wanted to start 100 petrol pumps. Secondly, I wanted to set up 1,130 outlets for jail products in the state’s 585 mandals (sub-districts). Earlier, they would not find markets. So, they were not being produced. Once we created marketing opportunities, the production increased. Then, [we earned] from ayurvedic spas.

Every year, we were clocking 100% growth. So, this year, we are clocking Rs 40 crore. Next year, we would have reached Rs 80 crore.

What was the procedure for families of prisoners to avail interest-free loans, and what were the amounts being given?

We used to look at a prisoner’s remaining tenure of punishment. He had to earn it, working for prison industries, and pay it back. The jail superintendent would look at the eligibility, and then recommend [the sum] to us.

I found that 80-90% of them were very poor--even Rs 20,000 was a big amount for their families. No banks would lend to them. But, we gave it to them, without any collateral or interest.

About 200-300 people availed [of the loans]. Mostly, life-imprisonment prisoners used to take loans, short-term prisoners were not eligible. They should have had a minimum of three years remaining in their term. Undertrial prisoners are not employed, so they cannot pay [a loan] back.

Despite all these initiatives, Telangana’s recidivism--at 6.1% for crimes under the Indian Penal Code and 5.8% for crimes under special local laws--is about the same as the national average. Why do you think this is the case?

Recidivism started going down, but not by a significant margin. But, I was sure I would be able to empty all the jails in some time-frame. In 10 years or so, there would be nobody in jails.

Also, we had drunken driving cases. So, the number of prisoners being reported was very high. But if you reduce these cases, you will find that change.

A recent report commends the “spectacular reduction in deaths--from 56 in 2014 to 8 in 2018” in Telangana prisons. How was this achieved and how can this be lowered further?

First, I arranged for master health check-ups to know their health condition. Second, [we ensured] cleanliness in the jail, and physical exercise. Through physical training, parades and classes, we kept them busy and meaningfully engaged. And then, there was a ban on smoking. We were very strict that ganja (marijuana), beedi (thin cigarettes), etc. could not be smuggled in easily.

All these helped reduce deaths. And we achieved this without spending any money.

Your 2017 initiative to rehabilitate beggars in Hyderabad, by rounding them up and detaining them in “Ananda Ashrams” (happiness shelters), was criticised--for not following due process of filing cases, etc, and for locking them up until a family member came to take them back. Your comments?

Hyderabad was full of beggars. Visitors used to call Hyderabad a city of beggars. I decided to make it beggar-free.

Some were professional beggars--they did not need to beg. Also, somebody [from their family] had to give an undertaking that they would not return to begging. The Prevention of Beggary Act had been notified in Telangana. So, we wanted to counsel them.

Once they were taken off the streets, somebody had to take them back. We don’t know who they are. If they vanish or if something happens to them, they will find fault with us.

They started learning many skills there. Most of them suffered from leprosy or infectious diseases. They were treated there. [This was] the ultimate service to humanity.

We closed about 15 sub-jails and there were more in the pipeline with just two, three or four prisoners. Why can we not turn these into shelters for destitute women, the elderly, orphans? The jail department has the expertise to lodge and board thousands of people, which no other body--including the municipal corporation--has.

We started a comprehensive package to keep them engaged--in physical training and parades, like [in] Sainik Schools [which train students to enter the defence services]. They attend hobby classes and moral [science] classes. In the evening, there is yoga, and then a sports class.

Everybody gave a declaration that they had come voluntarily [to the shelter].

How far were these declarations voluntary?

Most of them were willing. And, there were two choices: Either you go to an ashram shelter or come with us. But, you cannot stay at the crossroads. If you do, a case will be booked against you.

That is true, but detaining them without filing a case is problematic.

This is not detaining at all. We were taking prisoners’ declarations. Now anybody can say it was not voluntary but this can be disputed. You cannot pick up somebody unless you have documentary evidence. They are brought here, counselled and then they are left [to themselves].

About 90% of people wanted to stay there. As far as the contention that they are not allowed to leave is concerned, you will find that there is no policeman [at the shelter]--virtually, no jail staff. All are volunteers. And there is nobody at the gate.

But, they cannot leave until somebody comes to take them.

If they want to go, they can. They are free. But, we always insisted that somebody should come to take them away. People who were not beggars in the true sense of the term were taken away the same day.

(Madhavapeddi is a senior editor with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.