Basic Income Could Empower Millions Of Indians, But India May Find Cost Too High

In a country where 21% of the population lives below the poverty line (of Rs 816 per capita per month in rural areas, and Rs 1,000 in urban areas), where the top 10% of the population own 53% of its wealth, with worsening inequality over the last two decades, a basic income could empower millions, even as the government said the programme might not be politically or economically feasible.

“A basic income’s emancipatory value is greater than its actual value,” said Guy Standing, a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, who also implemented a basic income pilot programme in villages in Madhya Pradesh (MP) from June 2011 to November 2012.

Citing evidence from his study in Madhya Pradesh, he explains how extra money could reduce debt for the poor, and impact the scarcity mindset, which refers to people taking poor decisions because of a lack of money and hope for the future.

Though a universal basic income (UBI)--a periodic, recurring, unconditional cash payment to every individual--could, in theory, help reduce leakages from current welfare systems and improve the quality of life of the poor, there is mixed evidence on its impact, the long-term effects of cash transfers are under-researched, and it would be challenging to implement, based on an IndiaSpend analysis of current evidence.

If 75% of the population received Rs 6,450 per capita per year, the UBI would cost India 4.2% of its gross domestic product--more than the 2016-2017 central government revised estimate for the department of food and public distribution, defense services, expenditure on departments of agriculture, farmers' welfare, fertilizers, telecommunications, road transport and highways, and atomic energy put together.

The UBI amount would be greater than all current welfare programs of the government including the Public Distribution System, the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan, the Integrated Child Development Scheme, the Mid Day Meal scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana, the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana, and the Swachh Bharat Mission, according to the 2016-2017 economic survey.

UBI not a magic bullet, limited long-term evidence

“If you can reliably get cash to people, it is one of the most effective interventions to improve people’s lives,” said Paul Niehaus, professor of economics at the University of California, San Diego, and co-founder of GiveDirectly, an organisation which advocates giving cash to the poor. “But the debate (over UBI) is occurring in a vacuum, and there is a need for hard facts and rigorous evidence on the long term effects of a UBI.”

Two reviews of conditional and unconditional transfers (the closest to a UBI) found that both increased school enrollment but not learning outcomes in beneficiary families, compared to a situation when there were no cash transfers. Similarly, cash transfers can improve use of health services and dietary diversity but might not improve the weight and height of children.

“Complementary interventions and supply-side services can strengthen the impacts of cash transfers,” according to the 2016 review, such as better health infrastructure and communication programmes about the importance of using these services.

A basic income should be a right: Experts

It is “wrong for anyone to come between anyone and the resources they need”, said Karl Widerquist, associate professor at School of Foreign Service - Qatar, Georgetown University, and a proponent of the UBI. For him, the UBI amount should cover an individual's basic needs--food, clothing, shelter--and provide a cushion for emergencies, so that people do not struggle in their daily lives.

“In Utopia, published in 1516, Thomas More suggests a basic income as a way to help feudal farmers hurt by the conversation of common land for public use into private land for commercial use. In ‘Agrarian Justice’ published in 1797, Thomas Paine supported it for similar reasons, as ‘compensation for the loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property,’ It reappears in the writings of French radicals, Bertrand Russell, and of the the Rev. Dr. Martin luther King Jr.”, wrote Annie Lowrey in an article published in the New York Times Magazine in February 2017.

A basic income would be different from a payment for work done under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS) because it does not have a work requirement, or from a payment made to mothers choosing to deliver in a hospital as the UBI isn’t for a specific category of people. It is also different from a payment made to only those below the poverty line because the income is meant for everyone, irrespective of the level of income.

A universal basic income promotes “liberty because it is anti-paternalistic, opens up the possibility of flexibility in labour markets, promotes equality by reducing poverty, efficiency by reducing waste in government transfers, and it could, under some circumstances, even promote greater productivity”, said Chapter 9 of the 2016-2017, economic survey released in February 2017.

UBI as an alternative to current programmes: could correct faulty targeting, reduce leakage

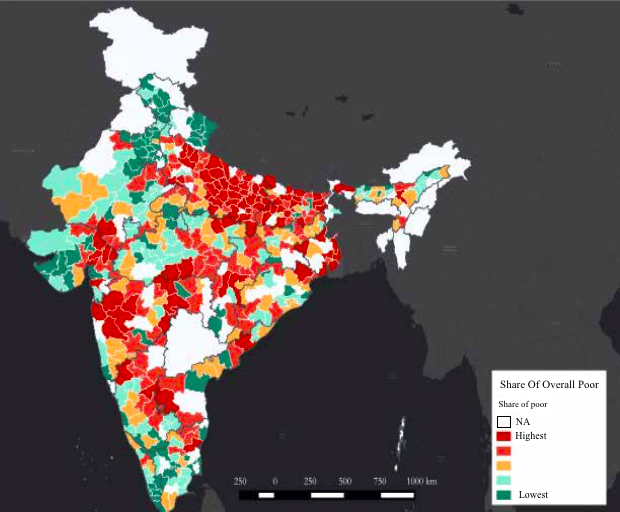

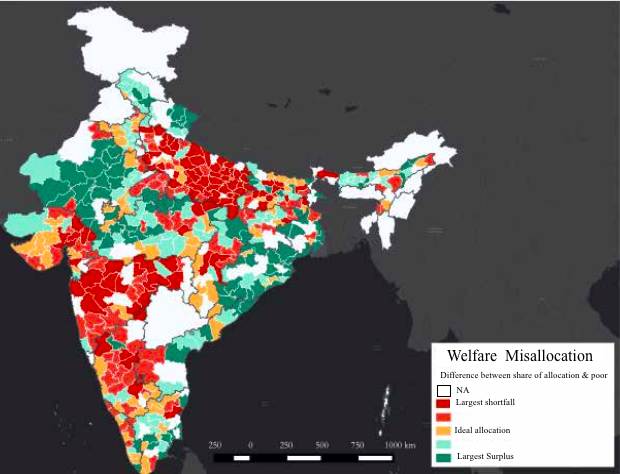

The 2016-2017 economic survey highlights the misallocation of funds in current programmes: it concludes there is little overlap between the share of poor in a district and the share of overall funding it receives from current welfare programs, suggesting the poorest districts do not receive the most money.

Share Of Poor Across Districts

Source: Economic Survey 2016-17

Misallocation - Shortfall in Allocation to Poor

Source: Economic Survey 2016-17

Supporters of the UBI point toward evidence that India’s current welfare programmes, such as the public distribution programme (PDS), have several problems including low quality in-kind products, and incorrect targeting, with many benefits reaching the non-poor and excluding the poor.

The proportion of households holding ‘below poverty line’ (BPL) or Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) cards, which qualify them for subsidised food from the PDS, increased from 36% to 42% between 2004-05 and 2011-12, because of an expansion of the programme, found a 2016 study by the Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office of the NITI Aayog, the government's think tank.

But “the programme has failed in efficient targeting and an increased proportion of cards have been distributed to the whole population”, and not only the poor, the study found. While 29% of BPL cardholders were poor, 71% were not poor. In contrast, about 13% of ‘above poverty line’ cardholders were poor while 87% were not, the study found.

A welfare system that does not need targeting, such as the universal income, could, in theory, avoid the cost of targeting, and errors in targeting.

But detractors of the UBI as a replacement for other welfare schemes point out the continuous improvement made in the implementation of such schemes. “...out of system leakage for the PDS overall could have reduced further to 20.8 percent,” from 54 % in 2004, the economic survey estimated.

A cash transfer could give beneficiaries greater freedom to spend the money on what they deem important. A PDS of in-kind transfers could reduce choice of food. Rising income of households was more likely to result in dietary diversity, (for example through increased milk consumption) for those that did not have APL or BPL cards, as cardholders were more likely to depend on cheaper cereals which were part of the PDS, the NITI Aayog study found.

“The transparency of a cash transfer would also reduce corruption. Everyone would know what everyone is supposed to be receiving,” said Standing, the researcher who was part of the MP basic income experiment.

Proving conditionality to become eligible for transfers can be an additional burden on the poor, with many opting out because they are unable to secure the necessary documents, such as proof of income or proof of an institutional delivery, Standing added.

UBI would cost 4.2% of GDP if 75% of the population received Rs 6,450 per capita per year

“There isn’t much quibble about the desirability of a UBI proposal that does not come at the cost of existing social benefits (health, education and social security),” wrote Reetika Khera, an economist at the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi, for the The Wire.

But the government currently does not have the resources to implement a basic income along with other welfare programmes, which together cost about 5% of the GDP by 2016-2017 budget allocations, the economic survey said.

The economic survey 2016-2017 pegs the cost of a universal basic income in India at 4.2% of the GDP, assuming a payment of Rs 6,450 per person per year, if 75% of the population avails of the transfer. At Rs 7,620 per year, a more apt basic income amount if only consumption levels of 2011-2012 are taken into account, the UBI would cost 4.9% of the GDP.

A study on cash transfers in African countries concluded that the cash transfer would impact food consumption if the value of the transfer was at least 15-20% of the value of existing consumption. It further said that timely and predictable payments facilitate investment and better planning by households.

An amount of Rs 6,450 per person per year would be equivalent to 37.5% of the 2011-2012 average yearly per capita consumption expenditure of Rs 17,159 in rural areas, and 20.4% of the expenditure in urban areas, based on data from the National Sample Survey Office. Poorer families would have lower consumption expenditure than the average.

Source: National Sample Survey Organization

Challenging to implement a basic income

To free money for UBI, the economic survey suggested removing subsidies that primarily benefit the middle and upper income population such as a subsidy for cooking gas or liquified petroleum gas (LPG), aviation turbine fuel, gold and fertilizer subsidies.

India’s finance minister Arun Jaitley said a basic income programme might not be politically feasible in India, because people will continue to demand existing subsidies even after a UBI, which would be unaffordable for the Indian economy, as reported by Livemint in June 2017.

“The government could unquestionably convert fuel (LPG) and electricity subsidies into a basic income,” says Niehaus, because these subsidies benefit the wealthy, who use more fuel and electricity, more than they benefit the poor. But to replace other welfare programmes, such as the PDS, by a basic income, or to raise revenue for UBI by increasing tax rates, needs more research, he explained.

Some said that the poor already receive too little. A UBI “doesn’t mean shuffling around the pittances we give the poor right now,” said Widerquist, the Georgetown University professor.

Instead of removing current programmes and implementing UBI, first maternity benefits and pensions should be universalised, which would cost 1.5% of GDP, suggested Khera, the IIT Delhi economist.

It might also be difficult for people to access the UBI. More people live closer to a fair price shop than a banking correspondent or an ATM, said Niehaus, which means that accessing cash transfers might be costly for people both in terms of the money to reach a bank, and in the time spent on accessing the money.

Niehaus gives the example of a successful project in Andhra Pradesh which provided cash payments to beneficiaries of the NREGS, and pensions, through a village-based payments system. The intervention included posting a banking correspondent in every village, and taking the payments system closer to the people rather than asking them to go to a post office. “This was a big reason for people preferring cash over in-kind transfers,” Niehaus said.

It would be better for the government to work with non-governmental agencies that have a local connection rather than implementing UBI alone, suggested Standing, based on his experience with the basic income pilot in Madhya Pradesh. The study found that basic income linked with activities of a local NGO “produced better results vis-à-vis families using health and education services”, and also made households less averse to taking risks. It also made the process of connecting with villagers, and convincing them to participate in the pilot easier.

Not everyone wants a cash transfer

A high proportion of Indians use welfare systems such as the PDS, with use growing from 27% of all households purchasing cereals from the PDS in 2004-2005 to 52.3% by 2011-12, found the NITI Aayog study. Any new system would have the ensure that all eligible beneficiaries can access the new programme.

“India’s size and diversity warns against adopting a one-size-fits-all cash policy that risks leaving India’s poor with cash in hand but nowhere to spend it,” wrote Saksham Khosla, a research analyst at Carnegie India in 2017, citing factors such as “socio-cultural norms, demographic idiosyncrasies, the efficiency and presence of local markets, and access to banking facilities” as reasons why some people prefer in-kind transfers and some cash payments.

For instance, he explained, a survey of rural households conducted in nine Indian states in 2011 found that nearly two-thirds of all respondents preferred in-kind food transfers over cash, as did a 2012 survey of the Mukhyamantri Balak and Balika Cycle Yojana in Bihar. On the other hand, a nationally representative household survey conducted 2016 found that about 53% of households preferred cash transfers in comparison to 29% in favour of in-kind foodgrain transfers.

The economic survey also suggests a “give-it-up” option for the rich who do not want to avail the UBI, similar to the LPG scheme enacted by the BJP government. A form of self-targeting might work--the time of the rich is too valuable to go through the process of getting a small cash payment.

India’s universal basic income pilot: Improved nutrition, no rise in alcohol use

A group of researchers, along with the Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), a trade union, implemented a basic income pilot in eight Madhya Pradesh villages (while keeping 12 villages as control villages for comparison), one tribal village and control village, and paid Rs 200 per adult and Rs 100 per child per month from June 2011 to May 2012 (between 20 and 30% of the income of lower income families there).

At the end of the pilot, more households in the basic income villages had improved toilet facilities, access to better lighting and cooking facilities, household assets such as vehicles, televisions, dish TVs and furniture, greater food security, higher school enrolment, especially of girls in secondary school, fewer dropouts from school, reduction in child wage labour, and higher improvement in nutritional status of children measured by weight for age, according to the study’s findings.

The cash transfers under the project were not given in lieu of other welfare programmes, such as the PDS, so the experiment cannot conclude whether cash is better or subsidies, the authors cautioned.

The basic income also resulted in slightly lower borrowing for hospitalisation, and smaller increases in general debt of the household.

In the tribal villages, the basic income enabled small farmers to invest extra funds into seeds and fertilizers, and spend more time on their own farms, rather than working on other people’s farms.

The basic income also led to higher consumption of fresh vegetables and milk. The change in consumption was greater in tribal households, which reported a substantial rise in consumption of more nutritious food such as pulses, vegetables, eggs, fruits, fish and meat, according to the study. Contrary to popular belief, use of alcohol did not rise in either the general or tribal households.

Further, instead of making people lazier, households receiving basic income had nearly 32% higher odds of working more hours than households not receiving the payments.

Several countries are implementing UBI pilot programmes

There is no country which provides a universal basic income, but the state of Alaska, in the United States, since 1982, provides all its citizens, including children, a permanent dividend from mining income to the state. Each person received $1,884 in 2014 and $2,072 in 2015.

In 2016, Switzerland voted against a proposal to provide a basic income to every Swiss and foreigner who had resided in the country for five years, The Guardian reported in June 2016.

But several other countries are implementing pilot programmes of the universal basic income. The table below has details.

| Countries Running Universal Basic Income Pilots | |

|---|---|

| Country | Project |

| Finland | monthly basic income of â?Z560 to 2,000 unemployed people between the ages of 25 and 58 for two years. The basic income replaces their unemployment benefit, but will continue even after they find work. |

| Ontario, Canada | project in three cities, enabling people to receive receive an annual basic income of $16,989 |

| California, USA | each person in 100 families receives $1,000 to $2,000 per month for six months to a year |

| Kenya | Implemented by Give Directly, transfer of about $23 a month to 40 villages for 12 years, and to 80 villages for two years |

Source: The Guardian, Quartz, Quartz, Give Directly

(Shah is a reporter/writer with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”