As India Hosts Global Desertification Meet, A Third Of Its Land In Crisis

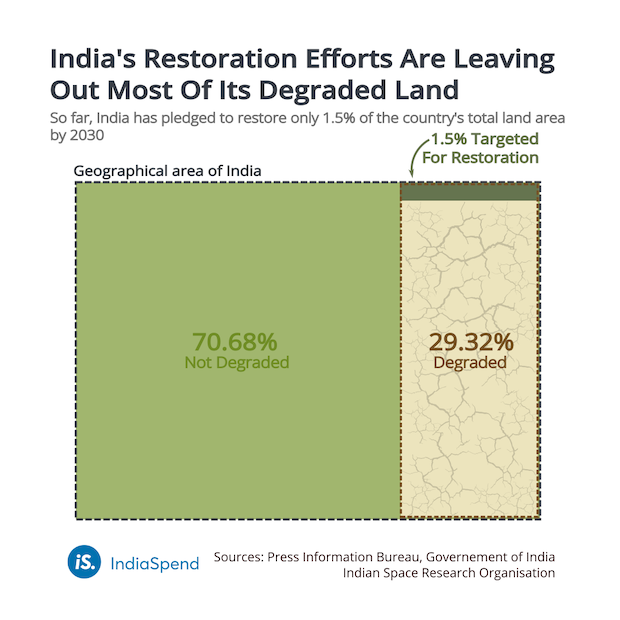

New Delhi: Even as it prepares to host a global conference on rising desertification, India faces a growing crisis of land degradation: Nearly 30% of its land area, as much as the area of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra put together, has been degraded through deforestation, over-cultivation, soil erosion and depletion of wetlands.

This land loss is not only whittling away India’s gross domestic product by 2.5% every year and affecting its crop yield, but also exacerbating climate change events in the country which, in turn, are causing even greater degradation, as we discuss later.

How can countries slow down this loss of land and biodiversity that threatens global food security and hastens climate change, impacting 3.2 billion people all over the world?

This question will lead discussions at the 14th Conference of Parties (COP 14) of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), starting on September 2, 2019 in New Delhi. This is the first time India will host this biennial gathering of 196 countries, scientists, private leaders, industry experts and non-profits.

Ahead of the event, India has pledged to restore 5 million hectares of degraded land by 2030. But this is just 1.5% of the country's geographical area, 28.5 percentage points less than the total land left degraded.

For countries like India that are highly vulnerable to climate change, land degradation is a critical issue. Degraded land loses its capacity to absorb carbon-dioxide (CO2), a greenhouse gas (GHG) that is the biggest factor in worsening global warming.

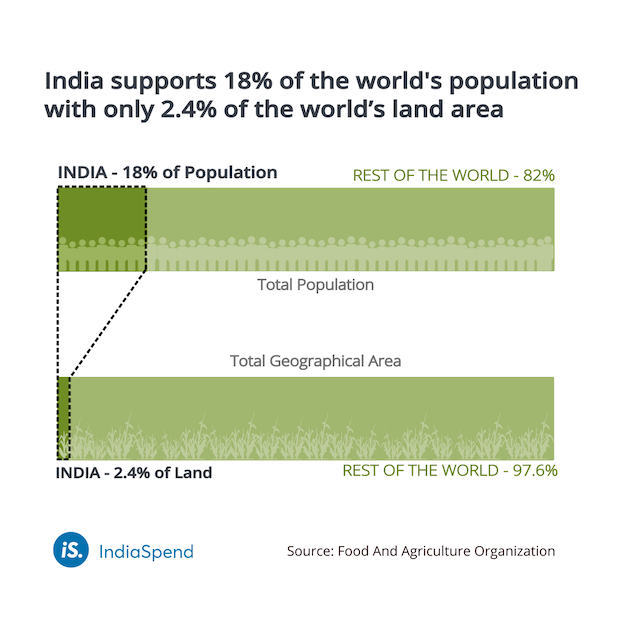

Over 600 million people risk the impact of climate change in India and if land degradation is not addressed, the problem could get more acute. The country is home to 18% of the world's population with only 2.4% of its land.

To halt land degradation, countries need to halt land-use change, work on forest conservation and step up land restoration, as per ‘Special Report on Climate Change and Land’, the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This report will inform the deliberations at COP 14 in Delhi and the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP25) scheduled to be held in Chile in December 2019.

Some of the findings in the report have significant implications for India where forests and wetlands (mangroves, marshes and swamps) cover 23% and 5% of the country’s geographical area, respectively, but are getting depleted fast.

Better land management

The emission of GHGs like CO2 through human activities has raised global temperature by 1 deg C post the industrial revolution of the early 19th century, leading to increased intensity and occurrence of extreme events such as heatwaves, droughts, cyclones, wildfires, heavy rainfall and floods, said an October 2018 report by the IPCC.

The IPCC, requested by the signatories of the Paris Agreement of 2015 to study the link between land and climate change, had published the August 2019 report.

Land degradation, as we said earlier, is caused by extreme weather events and this, in turn, is impacting the earth’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide, further speeding up climate change. These statistics show why land degradation needs concerted global action:

- Over 1 million species on earth are on the verge of extinction, threatening global food security, largely due to habitat loss and land degradation

- Three out of every four hectares of land have been altered from their natural states and the productivity of about one in every four hectares of land is declining

- Land degradation in tandem with climate change and biodiversity loss will force up to 700 million people to migrate by 2050

The global food system--including pre- and post-production activities--accounts for 37% of total human-caused GHG emissions. Agriculture, deforestation and other land-use activities specifically account for 23% of GHG emissions from human activities, said the report on land degradation.

People currently use one-fourth of land’s production potential for food, feed, fibre, timber and energy, directly affecting more than 70% of the global ice-free land surface, as per the report.

Why India should worry

Here are some findings about land and climate change from the latest IPCC report that have particular implications for India:

Forests: About 23% of GHG emissions from human activities come from the overuse of chemical fertilisers, soil erosion, deforestation and change in land use, as mentioned earlier. Managing these resources is important as they are fast depleting.

Forests are one of the most important solutions to climate change. India has lost 1.6 million hectare of forest cover over 18 years to 2018, about four times the geographical area of Goa, Hindustan Times reported on April 26, 2019. The government allowed felling of more than 10 million trees in India over five years to 2015.

Over 500 projects in India’s protected areas and eco-sensitive zones were cleared by the National Board of Wildlife over the first four years of the Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance government between June 2014 and May 2018. In comparison, the preceding United Progressive Alliance government had cleared 260 projects between 2009 and 2013, IndiaSpend reported in September 2018.

To fight climate change the Indian government has pledged to get 33% of its geographical area under forest cover by 2022, compared to the existing 24%. This would require the government to increase the forest cover by nearly 2% every year till 2022. Forest cover in India, however, increased only by 1% over two years to 2017.

Degradation of India’s forests is depriving the country of 1.4% of its GDP annually, according to a study by The Energy and Resource Institute (TERI), a Delhi-based non profit, that IndiaSpend cited in this June 2019 report.

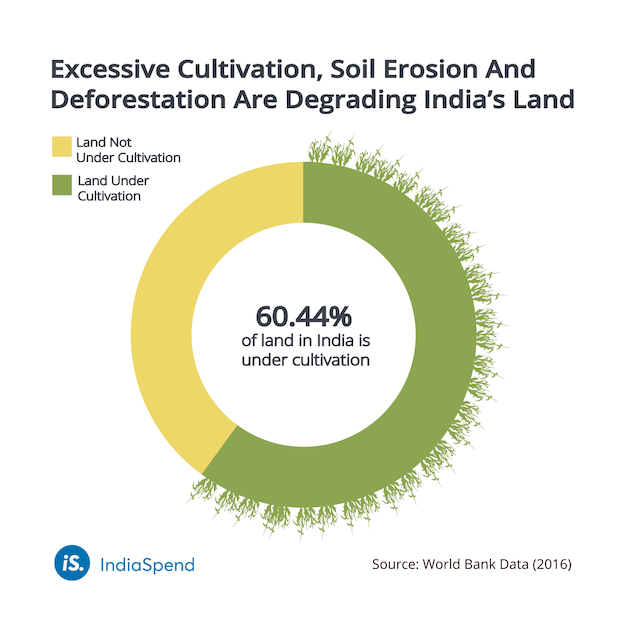

Food Security: Upto 60% of land in India is under cultivation contributing 14% to its GDP. It is one of the most vulnerable sectors in the country to be affected by increasing extreme weather events caused by global warming. Most affected are the small and marginal farmers owning less than two hectares of land, who make-up about 80% of the total farmers in India.

Climate change could cause food insecurities in countries by affecting crop yields, decreasing their nutrient content and affecting the growth and productivity of pastoral animals, said the IPCC report on land. Cereal prices could rise up to 23% by 2050 due to climate change making it unaffordable for the poor, it said.

For agrarian economies like India--which is the world's largest producer of milk, pulses and jute, and ranks as the second largest producer of rice, wheat, sugarcane, groundnut, vegetables, fruit and cotton, as per United Nations’ data--the findings of IPCC report are significant.

Soil degradation due to salinity and erosion due to water and air caused by extreme weather events and other human activities in India incurred losses of Rs 72,000 crore ($10.68 billion)--more than the agriculture budget of Rs 58,000 crore ($8.54 billion) in 2018-19--according to the TERI study.

This issue is pertinent for India, as the country struggles to feed its growing population: India was ranked at 103rd position in 2018 among 119 countries on the Global Hunger Index, three spots down from 100th in 2017.

Wetlands: Wetlands are critical in the fight against global warming, the IPCC report said, because they conserve “high-carbon ecosystems” that quickly absorb a high amount of carbon. Reclamation of degraded soils, afforestation and reforestation need “more time” to make similar impact.

India’s wetlands cover around 152,600 sq km, nearly 5% of the country’s geographic area and nearly twice the size of Assam. But deforestation, climate change, water drainage, land encroachment and urban development are depleting these wetlands--every year, 2-3% of their total area is being lost across the country.

Water Scarcity: The dryland population vulnerable to water stress and drought intensity is projected to reach 178 million under the most ideal conditions of 1.5 deg-C warming by 2050. The stressed population will increase to 220 million at 2 deg-C, and 270 million at 3 deg-C warming, said the IPCC report on land.

This has significant implications for India where about 69% of the total geographical area is under dry lands that include arid, semi-arid and dry sub-humid stretches.

With 600 million people facing extreme to high water stress, which is about half of the country's population, India is the 17th most water-stressed country in the world, tailing the countries which receive almost half the annual rainfall as India, IndiaSpend reported on August 6, 2019.

Rights of indigenous people: “Insecure land tenure affects the ability of people and communities” to fight climate change, said the IPCC report. Recognition of the customary tenure of indigenous people who have knowledge about local ecosystems like forests, and involving them in the decision-making and governance can help advance the efforts against climate change, the report added.

In India, the Forest Rights Act (FRA), which was passed in 2006, could be an important tool for climate actions. The Act recognises the rights of tribespeople and other traditional forest dwellers to access, manage, protect and govern the forestland and natural resources that they have been using for generations.

But the process of recognition of rights under FRA is slow: The government has only been able to settle FRA claims over 12.93 million hectares of forests as on April 30, 2019, against a potential of 40 million hectares of forestland across the country.

An ongoing case in the Supreme Court of India also threatens to evict 2 million forest dweller families whose FRA claims have been rejected. Currently, 21 state governments are in the process of reviewing all the rejected claims.

Solutions Box:

IPCC’s special report on land and climate change also evaluated some solutions to use land as a tool against global warming:

- There are two types of solutions: Those with immediate impact such as conservation of wetlands, rangelands and mangroves which absorb huge stocks of GHGs like CO2 from the atmosphere. There are other solutions that are more long-term: Planting of trees, reforestation and afforestation.

- Avoiding, reducing and reversing desertification would enhance soil fertility and increase carbon storage in soils and biomass while benefiting agricultural productivity and food security. Prevention of desertification is, however, preferable to attempts to restore degraded land.

- Over 30% of food is wasted or lost globally, which contributes to 10% of total GHG emissions from human activities. A number of response options such as increased food productivity, dietary choices and food losses and waste reduction can reduce the demand for land conversion. This could free land and create opportunities for enhanced implementation of other strategies listed here.

- Creation of windbreaks through afforestation, tree planting and ecosystem restoration programmes that can function as “green walls” and “green dams” that reduce dust and sandstorms and sand dune movement.

(Tripathi is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.