988 Mn Indians Do Not Have Life Insurance. Those Who Do, Are Insured For 7.8% Of What's Needed To Cover Financial Shock

Chennai: At least 988 million Indians--more than the population of Europe and 75% of all Indians--are not covered by any form of life insurance, and an Indian is assured of only 8% of what may be required to protect a family from financial shock following the death of an earning member, according to our analysis of government data and industry data.

Unexpected shocks such as the death of a family member lead to financial loss. The lack of adequate cover in these situations makes people prone to high financial instability. This is more severe in the case of the unorganised sector: Informal workers in the unorganised sector are exposed to additional risks in the form of income volatility, hazardous workplace conditions and lack of old-age benefits. These risks can be reduced through insurance.

With 82% of India's workforce engaged in informal employment in the unorganised sector, 392.31 million workers and their families--more than the population of United States--live under constant threat of financial setbacks due to insufficient or non-existent coverage.

India had about 328 million life insurance policies in 2017, according to data from the Handbook on Indian Insurance Statistics, 2016-17, of the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI). Assuming each policy corresponds to a unique citizen, this accounts for 25% of the population having life insurance cover, leaving 75%--or 988 million Indians--without cover.

Considering a person may hold more than one such policy, the number of Indians not covered by life insurance may be higher. Currently, there are no data on the number of unique Indians with life insurance cover.

Further, an average working person is assured of, as we said, only 8% of what may be required to protect a family after the death of an earning member, according to our analysis of data by leading global reinsurer Swiss Re. This is much lower than the insurance coverage adequacy of 44% in Japan, 84% in Taiwan and 67% in Australia.

“There are low levels of insurance penetration (life and non-life) despite numerous sources of risk such as rainfall (leading to income shocks in largely agrarian segments of the population), health shocks, and catastrophes such as floods or cyclones,” the July 2017 Household Finance Committee report of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) pointed out.

India at par with emerging markets in coverage--but, the devil is in the details

Globally, three standard metrics are used to understand insurance cover: Annual premium growth, insurance density and insurance penetration. However, these do not reveal the actual picture, as we will explain later.

1. Annual premium growth: India’s total real premium growth rate for life insurance--the annual rate of increase in premium collected by the life insurance industry in real terms i.e. adjusted for inflation--is 8%, according to the IRDAI’s 2017 annual report.

While this is better than Brazil’s 1.2%, it is lower than Russia’s 48.2% and China’s 21.1%, data show.

2. Insurance density is the ratio of insurance premium--the price paid by consumers for insurance cover--to population.

India’s life insurance density (adjusted for purchasing power parity) was $811.3 in 2016--ahead of Brazil ($390) and China ($659.7) but below the UK ($2,129.3), USA ($1,724.9) and South Africa ($2,611.7, according to data from the IRDAI Annual Report, 2017.

3. Insurance penetration is the ratio of insurance premium to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

India’s life insurance penetration was 2.72% in 2016--comparable to Brazil (2.28%), China (2.34%) and the US (3.02%), but lower than South Africa (11.52%) and the world average (3.47%).

These figures suggest that India is at par with other emerging markets. But, the devil is in the details.

For instance, there are no data, as we said, on the number of unique individuals covered. Further, the data do not provide insights into the variations across income classes, social groups, occupations and geographies.

These metrics also do not give clarity on whether the protection provided is adequate to cover financial shock.

The Indian government’s Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation acknowledges that the “statistical information currently available on insurance is scattered and inadequate”.

Let us take the example of personal accident insurance in India to understand this.

Understanding the lack of data: The case of personal accident insurance

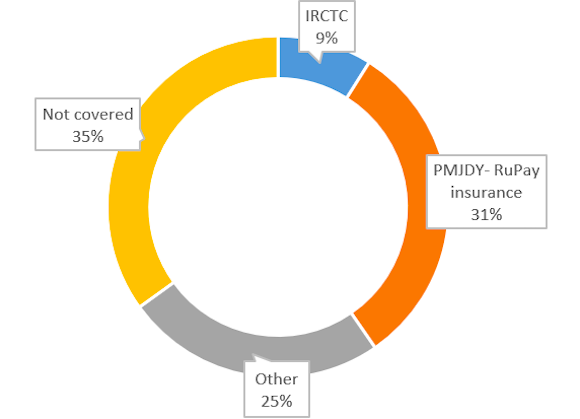

Personal accident insurance usually covers death or disability caused due to an accident. As of 2017, 65% Indians are covered by personal accident insurance, according to data from the IRDAI’s 2017 annual report.

This includes policies issued under Indian Railways Catering and Tourism Corporation (IRCTC), Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) and Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana (PMSBY).

Source: Table I.62, IRDAI Annual Report, 2017

IRCTC personal accident insurance is available only for passengers travelling through the Indian Railways with an e-ticket, and is valid for only the duration of that particular journey. It does not cover people travelling in unreserved compartments on passenger trains, and those commuting on suburban trains.

PMJDY accounts offer RuPay insurance as a special benefit. But this covers only those account holders who have made a transaction within 90 days (for non-premium cardholders) or 45 days (for premium card holders) prior to the date of accident, according to the scheme guidelines.

Over 20% of PMJDY beneficiaries haven’t even been issued RuPay cards, PMJDY data from December 2016 show. Further, 48% of people holding an account with a financial institution--banks, credit unions, microfinance institutions, cooperatives and post offices--have neither deposited nor withdrawn in the past year, according to the 2017 Global Findex released by the World Bank.

So, they cannot avail RuPay insurance even if they have a PMJDY account.

If we exclude PMJDY and IRCTC schemes, the personal accident coverage of the country’s population reduces to 25%.

So, how best can insurance coverage and adequacy be measured?

Let us understand what other metrics we can use to measure insurance coverage along with adequacy and how India fares with respect to these metrics.

1. Sum assured to GDP ratio

A metric that comes close to measuring the extent of coverage is the sum assured--the money that is paid to families after a death--to GDP ratio.

The total sum assured accounts for 58% of India's GDP, according to this 2013 RBI report. This is more than that of China (33%) and Indonesia (28%) but much behind the US, Germany, South Korea and Japan where it is in the range of 105%-321%, illustrating the poor quality of cover in India.

As of March 2017, the sum assured to GDP for life insurance in India is 65%, according to our analysis of data from the IRDAI’s 2017 annual report and the handbook mentioned above.

2. Mortality protection gap and protection margin

The global reinsurer Swiss Re uses mortality protection gap and protection margin as metrics to assess the adequacy of insurance coverage.

Mortality protection gap is the difference between the resources needed and the resources already available for the family to maintain their living standards, in the event of death of a working family member. Protection margin is the ratio of protection gap and protection needs.

To understand this, let us consider a three-person low-income household with a school-going child and working parents. In the event of the mother’s death, the household income would suffer, the child’s education would be at risk and the very survival of the child and her father would become difficult, as they may not have enough resources to live on.

Let us assume that after the death of the mother, the family has some savings in the bank and the amount claimed from life insurance. The protection gap would be the difference between this amount and the resources they need to fund necessities such as food, healthcare and education. The protection margin would be the ratio between this protection gap and the actual protection needed to nullify the effect of the mother’s death on their financial lives.

India has the highest protection margin in the Asia Pacific region at 92.2%. This means having savings and insurance of just Rs 7.8 for every Rs 100 needed for protection, leaving a protection gap of Rs 92.2.

Further, India’s mortality protection gap rose 11% every year, on average, over the past decade, data show.

Why aren’t Indians sufficiently covered?

Most insurance products in India are not pure protection products, but are endowment products that offer protection and investment features, according to this 2017 report by McKinsey, a global consultancy.

For instance, of the 21 life insurance plans offered by India’s Life Insurance Corporation (LIC), the largest player in India’s life insurance market with 70% market share, only three are pure protection products.

Insurance cover offered by endowment insurance products tends to be much lower than that offered by pure protection products.

Most Indian seeking insurance rely on the insurance agent’s advice on what products to purchase. Insurance agents tend to market products that maximise their own well-being instead of products that are suitable for the consumer, this 2011 field study found.

To tackle the issues of awareness and underinsurance, the central and state governments have come out with schemes for risk protection, especially for the socially and economically vulnerable sections of the population. But these schemes are falling short of their objective of providing adequate risk protection for low-income households, as is reflected in our analysis.

We also need to go beyond conventional measures and explore more statistically rigorous indicators such as protection margin. Towards this end, the IRDAI should proactively provide data on coverage and sufficiency of coverage.

(Aparajita Singh is a Policy Analyst at Dvara Research, a financial policy research institution.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.