65% Indians Exposed To Heatwaves In May-June 2019. July 2019 Was India's Hottest Ever

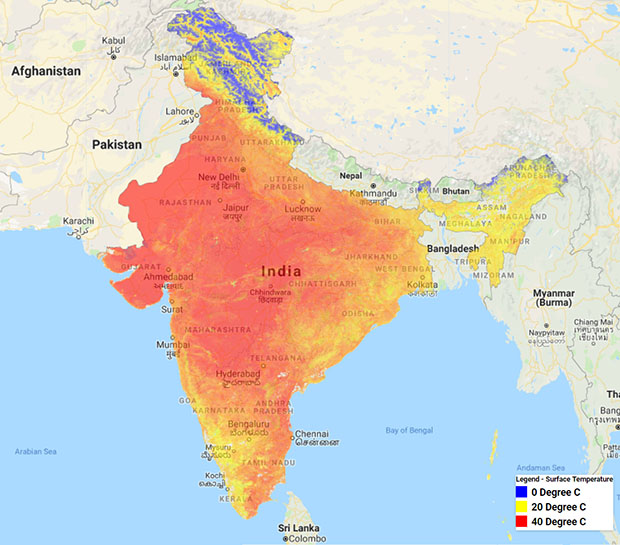

Bengaluru/Geneva: July 2019 was the hottest July ever in recorded Indian meteorological history, and 65.12% of India's population was exposed to temperatures of over 40 deg C between May and June, 2019, the most widespread over four years, according to a new analysis.

In 2016, 59.32% of India's population faced a heatwave, the number rose to 61.4% in 2017 and fell to 52.94% in 2018, according to an analysis done for IndiaSpend by Raj Bhagat Palanichamy, an earth observation expert at the World Resource Institute (WRI) in India.

It was only in 2016 that satellite data improved enough to yield such a detailed analysis, according to Palanichamy. But 2015 saw the worst heatwave in India since 1992, striking areas from Delhi to Telangana and killing 2,081 people. It was the fifth deadliest in world history.

On June 25, 2019, temperatures were as much as 5.1 deg C above normal in parts of Jharkhand, Assam and Meghalaya, according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD) which classified this as "markedly above normal". Temperatures were 3.1 deg C above normal in the sub-Himalayan West Bengal and Sikkim or, as IMD put it, "appreciably above normal".

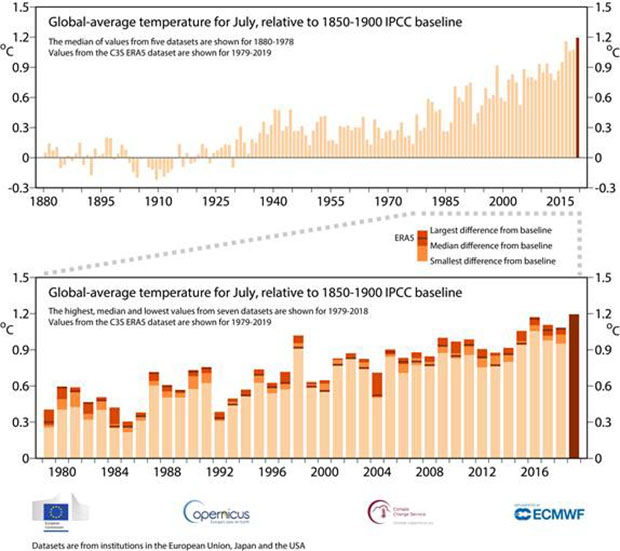

Global temperature records were broken during the summer of 2019, with the July temperature 1.2 deg C above the pre-industrial era, according to the latest data from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the Copernicus Climate Change Programme, the European Union's Earth Observation Programme.

As global CO2 (carbon dioxide) emissions continue to rise, heatwaves are likely to become more frequent, and more intense, according to the October 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body set up to assess science related to climate change. The consequences will be deadly.

India will see a four-fold rise in heatwaves if global temperature rise is restricted to 1.5 deg C by the turn of this century, according to a November 2018 study by Indian Institute of Technology-Gandhinagar researchers. If the world fails to contain global temperature rise, India could see an eight-fold rise in heatwaves.

This can lead to a rise in both morbidity and mortality. Heatwaves can cause the body's core temperature to increase. Limited exposure can lead to dehydration and dizziness but high exposure to heatwaves could lead multiple organs to dysfunction causing death within hours, studies suggest.

Between 2010 and 2018, 6,167 heat-related deaths were reported in India, as IndiaSpend reported in April 2019. The year 2015 reported the most fatalities: 2,081 or 34% of all heat-related deaths in that time period.

In 2019, 94 deaths were reported till June 16, according to a government statement to the Lok Sabha, parliament's lower house. This number rose to 210 by the end of June, with the most (118) deaths being reported from Bihar.

"A vast majority of deaths during a heatwave period are registered as normal deaths (from cardiorespiratory arrest etc) or might never be medically declared/certified heatwave deaths," said Gulrez Azhar, an epidemiologist and researcher who studied heatwave deaths in Gujarat for four years while at the Indian Institute of Public Health (IIPH), Gandhinagar. "But those deaths would not have happened had it not been so hot."

Along with day-time temperatures, night-time heat is rising as well.

"Most of the time we are focussed on looking at day-time heatwaves," said Vimal Mishra, associate professor at IIT-Gandhinagar, who co-authored the study and focuses on climate change research. "Cooler nights give some relief. But think about a scenario where both days and nights are hot."

These relentlessly hot days and nights are what his study predicts will become commonplace in coming years.

But India is not an exception.

Record temperatures across the globe and human influence

Global average temperatures for the month of July were close to 1.2 deg C above the pre-industrial level as defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S).

Bern, the capital of Switzerland, surrounded by the snow-clad Alps, reported an unusually warm summer this July. Temperatures reached up to 36 deg C, well above the average day-time temperature of 24 deg C for the month, and the Swiss government had to issue a rare level-4 heat alert indicating 'severe danger' from the heat.

France's capital Paris hit 42.6 deg C on July 25, an all-time high compared to the July average of 24 deg C. United Kingdom's capital London too recorded a temperature of 34 deg C against its July average of 22 deg C. Officials in Belgium issued a warning after the death of a 66-year-old woman was attributed to the heatwave.

The US too is bracing for record high temperatures across the country.

Greenland, a country where ice glaciers cover 82% of surface area, lost over 10 billion tonnes of ice on July 31, 2019. To put it in perspective, 1 billion tonne is equivalent to 400,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools. This also means that global sea levels will go further up.

The average global temperature for the previous month--June 2019--was the highest in recorded history as well. It was 0.1 deg C higher than in June 2016, which had held the record of being the warmest so far.

Human activity to be blamed

The science on the rising frequency and intensity of heatwaves is clear: human activity is to be blamed. Since the first such study in 2004, advances in attribution science have confirmed that human influence has made heatwaves more likely.

But linking a particular extreme weather event to climate change is tricky, said Freja Vamborg, senior scientist, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). "To do such studies you need very good observational data for a long time back," she said. "In some parts of the world such studies could be difficult as the observational data might not be homogenous."

What is a given, according to Vamborg, is that such heatwaves are likely to be the norm in the coming years.

A heatwave, as we mentioned, is not about crossing a particular temperature level but how much it exceeds the average temperature of a particular place. In northern India, for example, a heatwave would warrant temperatures above 40 deg C but in Switzerland this would be 29 deg C and above.

However, in places that routinely deal with high temperatures, people develop different kinds of coping mechanism. But in regions used to temperate summers, people are unprepared for heatwaves. France alone has reported five heatwave deaths so far.

But even in India, used to hot summers, some areas could well become unlivable with a further rise in temperature, according to experts.

If CO2 emissions are not contained, then India, Pakistan and Bangladesh would be swept by deadly heatwaves in the next few decades, said a 2017 study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The impact would be especially severe in the Indo-Gangetic plain, the study said.

Upto 37% of Indians were exposed to high temperatures (air temperature) of over 40 deg C for 10 hours or more in a day in 2019, up from 27.42% in 2018, according to satellite data.

Data: GFS Temperature Estimates, GPWv4, MODIS (LPDAAC - NASA); Processed by Raj Bhagat Palanichamy using Google Earth Engine.

The heatwave-climate change link

Globally, CO2 emissions continue to rise and, of this, in 2017 nearly 7% came from India, up from 6% in 2016, according to a December 2018 report from the Global Carbon Project, a collaborative effort between several research institutes to quantify global greenhouse-gas emissions.

Being a greenhouse gas, CO2 traps the sun's heat, pushing up land surface temperatures. Higher than normal temperatures lead to heatwaves. So, the connection between climate change and heatwave is a direct one.

"We know that all the land surface areas--there are hardly any exceptions--have seen an increase in temperatures over the past 150 years," said Vamborg. "Some areas warm faster and some areas warm slower."

This relationship between rising temperatures and heatwaves is also non-linear. "What it means is this: If without a (global) increase in temperature you have five heatwaves in 10 years then, with a temperature rise of half a deg C you will have seven heatwaves in 10 years," explained Mishra of IIT-Gandhinagar. "And if the temperature rises by 1 deg C then all of a sudden there could be 20 heatwaves in five years."

But the impact of global temperature changes will vary across the globe. And rising humidity levels will be a factor in this.

"Air can hold up to 7% more moisture for every degree celsius rise in temperature," said Krishna AchutaRao of the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) - Delhi. Thus in coastal cities, where the air tends to be moist, humidity levels will rise with a rise in temperature. "When humidity is high the sweat stays on the body and there is no cooling effect," said AchutaRao. "That is why the heat during monsoon feels more oppressive."

While IMD takes into account only temperature rise when declaring a heatwave, scientists suggested a heat index that takes into account both temperature rise and humidity.

Damage from heatwaves

Depending on how much the temperature has risen, for how long and over how much land, a heatwave can impact human life in different ways.

"You may have intense heatwave in one year but it may be very localised as we witnessed in 2015 (in India)," said Mishra of IIT-Gandhinagar. "But this year's heatwave covered almost two-thirds of the country. So, if the intensity of the heatwave is the same but the area covered is two to three times more, we can expect more damage."

If no effort is made to adapt to these heatwaves, they could cause more deaths; but the fatalities would vary across areas, according to a 2018 study of 20 regions across the world published in the health journal PLOS. The highest increase in deaths could be in Colombia, followed by the Philippines and Brazil, the study said. Tropical and subtropical regions, including India, would see a rise in deaths.

Heatwaves have been linked to pre-term births, reduced fertility, increase in mental health issues, increase in farmer suicide rates in India and chronic kidney diseases.

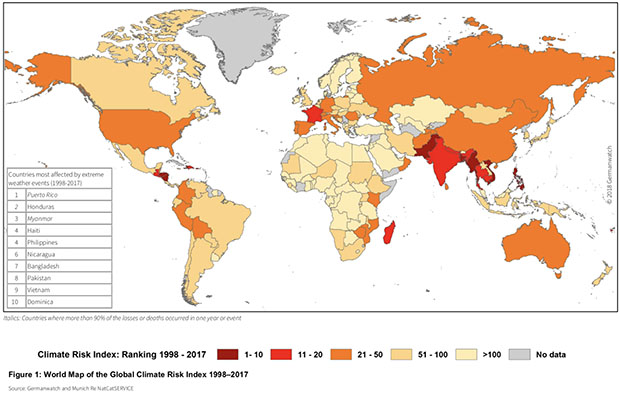

India is among the top 20 countries in the world to have seen the most number of extreme weather events between 1998 and 2017, according to a 2019 report by a German non-profit that tracks climate risk.

While pregnant women, the elderly, and children are particularly vulnerable, those affected will disproportionately be the ones without the means to escape the heat.

"The exposure to heat is related to economic class," said Shoibal Chakravarty, a fellow at the Centre for Environment and Development, Ashoka Trust for Ecology and Environment or ATREE. "It essentially has to do with who is so poor that you have to continue working in the heat."

Those working in the informal sector, especially vulnerable daily wagers, are most likely to be affected by heatwaves, according to Chakravarty, who studies equity in the context of climate change. In India, of around 61 million jobs created over 22 years since the liberalisation of the economy in 1991, 92% were informal jobs, according to an IndiaSpend analysis of National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data for 2011-12, the latest available, released in 2014.

This year 37% of the population was exposed to air temperature of over 40 deg C for 10 hours or more a day, according to the analysis by Palanichamy of WRI for IndiaSpend, highest in the past four years. In 2016, this number stood at 31.79%, rising to 34.19% in 2017 and falling to 27.42% in 2018.

Heatwaves also bring down productivity, according to initial results from an ongoing India-centric study at the Energy Policy Institute of the University of Chicago. Productivity declines by 2-4% with every deg C rise in temperature.

Parts of Greenland has seen temperatures 10 to 15 deg C above normal causing glaciers to melt, according to the World Meteorological Organization.

Is air pollution masking impact of heatwaves?

India is experiencing fewer heatwaves than projected by climate models, said a study co-authored by AchutaRao.

As climate change takes hold, the expectation is that extreme temperatures--the maximum temperature on the hottest day of each year in a region--would keep rising.

"In all the studies in the US, Russia and Europe that has happened, but not in India," said AchutaRao of IIT-Delhi. "But that hasn't happened in India. They've been flat and, in some places, even declined."

Scientists suspect that this can be traced to two factors: air pollution and irrigation. If India were to clean up its air, thus erasing the elements that block sunlight, heat levels are likely to go up, said AchutaRao. What is unclear is exactly how much the heatwaves will go up once pollution is taken out of the picture.

Air pollution is caused not just by the presence of gases but also aerosols (solid or liquid particles in the air). Some aerosols have a warming effect while others have a cooling one, as explained in an IndiaSpend story in May 2019. This means that depending on the nature of local pollution, humidity levels and surface water bodies, different areas will experience either a rise or fall in heat levels when that pollution clears.

Irrigation tends to have a cooling effect on the land. But this effect is small and localised. "Heatwaves occur in summer and most of the crops are gone by that time," said Mishra of IIT-Gandhinagar.

The way forward

Preparing for the future will involve two steps: mitigation and adaptation. "In terms of mitigating future heatwaves, the only way that the future heatwaves can be controlled is by controlling CO2 emissions," said AchutaRao. This would involve a global effort.

Focus on renewables to reduce CO2 emissions and protecting existing forests are other crucial mitigation measures. Adaptation would involve better urban planning with a focus on more tree cover and increasing surface water bodies that tend to have a localised cooling effect.

"An integrated approach to climate change and at least the management of heat and cooling in the country is required," said Chakravarty from ATREE. Even after all these measures, "heatwaves would still happen but their impact would be reduced".

(Shetty is a reporting fellow with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.