How Will—Unprepared—States Handle A $29-Billion Budget Bonanza?

Last week the Niti Aayog’s sub-group of chief ministers held a crucial meeting to discuss the future of Centrally-Sponsored Schemes (CSS) in India. CSS, a key instrument through which social-sector priorities are financed, have been at the centre of much public debate over the last month.

The report of the 14th Finance Commission, accepted by the Government of India in February set the stage for a radical re-haul of CSS by mandating a substantive increase in tax devolution to states from 32% to 42% of the divisible pool of union taxes.

A key implication of this increase is that states are set to receive a substantial increase in untied funds (funds without strings attached) that they can invest as they see fit. This is a marked departure from the past when more than half the money received by states arrived tied to pre-determined expenditure requirements in the form of non-plan grants, central assistance to states and CSS.

To put this in perspective, in 2010-11, tax devolution to states accounted for 44% of the total transfers. In 2015-16, this is as high as 62%. In addition, grants-in-aid recommended by the 14thFinance Commission, adding up to 13% of total transfers, have also been made substantially untied, relative to previous Commissions.

So, states will receive an additional Rs 1.8 lakh crore ($29 billion) in untied funds—money they can use as they choose—compared with the previous financial year.

The obvious implication is that “tied” central grants to states, most notably CSS and other forms of central assistance to schemes, have been reduced to create the fiscal space for this large transfer of untied funds to states.

Consequently, central tied grants, which in 2010-11 accounted for 46% of total transfers to states, now account for 25%, and as a result, the union budget for 2015-16 saw a significant reduction of central financial support for social sector programs financed through the CSS.

In the debate that followed, many serious concerns were—and still are—raised about the implications of this reduced spending on the social sector.

Mind the gap—and find the money to bridge it

The central government, on its part, has argued that these cuts are a natural consequence of the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission, and it is for the state governments to use their additional united resources to make up the gap.

While we agree with this in principle, the truth is that there is a lot of confusion over precisely how this is to unfold in practice.

The budget documents have offered some hints by categorising CSS into a) schemes that are to be discontinued, b) schemes that are to be “fully funded” by the centre (i.e. the current system remains unchanged) and c) schemes that are to be partially funded by the centre (see table below).

| What’s Changed, What’s Not | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type of Scheme | No. of Schemes | Change from last year |

| Discontinued/delinked from Central support though states can continue to fund

| 8 + 16 | -100% |

| States will need to shoulder a greater share of resources

| 24 | -44% |

| Centre to continue to bear full share

| 31 | 0% |

However, the budget has offered no clarity on what the revised sharing pattern will be. To add to the confusion, most state governments have already passed their 2015-16 budgets and central ministries are expected to approve the annual plan and budget for states for CSS within the next few weeks.

How these specific budget allocations for CSS will be determined, in the absence of any clear sense of the quantum of finances that the states and Centre are expected to give to schemes, remains a mystery!

There are also important concerns over whether states have adequate fiscal space to maintain current levels of budgetary allocations for key social sector schemes, given the cuts in budget.

It is amidst these concerns that last week’s meeting gains significance.

How about using the money that is available?

Reports suggest that the sub-group is going to prepare a road map for restructuring CSS by the end of April. But even as the sub-group goes to the drawing board to consider the future of CSS, it is worth stepping back to reflect on what we know about CSS and whether the 14th Finance Commission recommendations can be used as an opportunity to genuinely address some of the key limitations in how CSS are financed today.

Here are a few facts:

To begin with, for all the current concern over cuts in social sector budgets in 2015, most states find it very difficult to spend their allocated budgets in any given year.

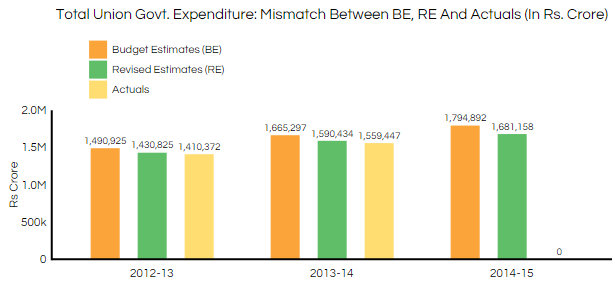

It’s important to note that there are three different figures which can be used to analyse the budget. At the start of a financial year, the government states its expected requirement of funds—these are called budget allocations or budget estimates (BE) in public finance parlance. In December, the estimates are revised based on expenditure incurred so far–these new estimates are called revised estimates (RE). Finally, there are the funds that are actually spent–these are called actuals. As the figure below highlights, there is a huge mismatch between the BE, RE and actuals.

Source: Union Budget, “Budget at a Glance”, for years 2015-16, 2014-15, 2013-14. Actuals for 2014-15 kept as 0.

How does this play out at the level of specific schemes? Between April 2007 and March 2013 for instance, of the Rs 1.69 lakh crore ($27.2 billion) allocated for the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, only 69% was spent.

Similarly, for the Swachh Bharat Mission, till February 2015, the centre had released only 33% of total budgeted allocations (BE). Consequently, revised estimates (RE) were 38% lower than BE in 2014-15. In a scenario of decreased allocations, this gap will need to be drastically reduced.

What explains these gaps in spending?

Stifled and controlled by New Delhi

The truth is that the Indian government finds it very hard to plan, transfer and spend money appropriately.

And whilst much public energy has been spent on debating the problem of corruption in social sectors, the bigger evil that plagues social sector spending in India is the high levels of centralisation in CSS, which allows the centre to pre-determine priorities by tightly controlling the line-item budgets prepared by states.

Consequently state priorities are often undermined in the final budget approvals. This is evident from a close reading of the planning and budgeting documents for the CSS.

Consider the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan (Universal Education Scheme), or SSA. In one instance, a state government needed money to restructure its teacher-training model. However, the proposal was not aligned to the prescribed central framework and funding was denied.

In another instance, a state government that was already running a substantive uniforms program through its own budget was forced to accept central money for the same activity because the SSA guidelines mandated it!

Not only does this mean that funds approved are rarely aligned to needs, it also suggests that states have relatively little incentive to plan. As a result, budgetary allocations rarely reflect needs and priorities on the ground, which is an important reason why spending can be difficult.

To add to this, the planning process is extremely unpredictable. States are a rarely given a budget envelope at the start of the plan process and as a result rarely get all the money that they ask for.

In 2014-15, the Centre approved only 58% of total proposals by states for SSA. Similarly, in the National Health Mission (NHM), only 60% of state proposals under the National Rural Health Mission flexible pool were approved.

These gaps in planning are exacerbated by the fact the fund-transfer system for CSS is extremely opaque and slow. Consequently, states, districts and service delivery facilities have no prior information on the timing and quantum of money that they can expect to receive, making it difficult to plan spending.

In 2014-15 for instance, only 15% of allocations for the Swachh Bharat Mission were released in the first two quarters of FY 2014-15. Similarly, only 29% of allocations were released for NHM in the first quarter of FY 2014-15, down from 46% in FY 2013-14.

Faced with these constraints, even a well-intentioned administrator will find it difficult to get things done. Often, inaction may be a deliberate strategy to deal with financial constraints.

Money and results have little in common

But perhaps the greatest limitation of the current model of CSS is that planning and budgeting is rarely linked to an assessment of outcomes sought through programs.

Data on performance—whether learning levels or quality of health facilities—is rarely collected, and when it is, this is not part of the annual planning exercise. Consequently funds are allocated year after year with little progress on outcomes. The entire delivery architecture—irrespective of whether financed through the centre or states — is incentivised to plan, budget and spend money with no consideration for the outcomes of this spending! No surprise, then, that we are a long way away from ensuring that outlays match outcomes.

The proposed effort to restructure CSS in line with the 14th Finance Commission recommendations is a unique opportunity to address some of these imbalances.

For one, just the fact that state governments have more access to untied resources and—if newspaper reports are to be believed—are expected to provide a greater share of resources to CSS than in the past.

This will loosen the Centre’s control over the purse strings and allow states to take the driver’s seat in designing CSS implementation appropriate to their needs. This will help improve overall spending, as budgets are more likely to be aligned to spending needs.

But, even as states take the driver’s seat, there are legitimate concerns over state capacity, both administrative and fiscal to ensure that CSS are implemented well.

It is our contention that a well-designed restructuring can go a long way in addressing these concerns.

For instance, CSS could serve to incentivise performance across states by introducing performance rewards and setting up innovation funds for states. Not only would this ensure inter-state competition for effective, performance based spending, it will also force line ministries to set up effective monitoring and evaluation processes to assess outcomes.

Ultimately, effective administration of programs, whether centralised or decentralised, requires that the nuts and bolts are in place so that administrators can do their job.

As we’ve highlighted here, in its current architecture, the government of India is unable to efficiently and effectively push money through its administrative chain. Infusing transparency and streamlining fund flows in the newly restructured CSS will be essential.

Image Credit: Press Information Bureau

(Aiyar, Kapur and Srinivas are with Accountability Initiative, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi)

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”