Education Failure, Leading Reason For UP Job Woes, Isn't An Election Issue

Eight-year-old Saidun Ahmed, left, on her way to school in Fattepur village, Mirzapur district in eastern Uttar Pradesh, said she couldn’t read well. Poor quality education and high absenteeism plague government schools in the state.

Bahraich and Mirzapur districts (Uttar Pradesh): “Path mera alokit kardo, naval prath ki naval rashmiyon se, mere ur ka tam har do,” Saidun Ahmed, 8, recited a Hindi poem by Dwarika Prasad Maheshwari, a twentieth-century poet, at top speed. “Light up my path, with the morning sunlight light of the new sun, overcome the darkness within my heart.”

But when asked to read some lines on the opposite page, the fourth grader, dressed in a button-up full-sleeved brown shirt and skirt--the school uniform of all government schools in Uttar Pradesh--said she had memorised the poem and couldn’t read well.

“Children don’t learn much in the government school,” said 37-year-old Iklakh Ahmed, her father, a driver by profession. “I will enroll her in the private school next year.” Saidun’s family lives in Fattepur, a village in the eastern Uttar Pradesh (UP) district of Mirzapur.

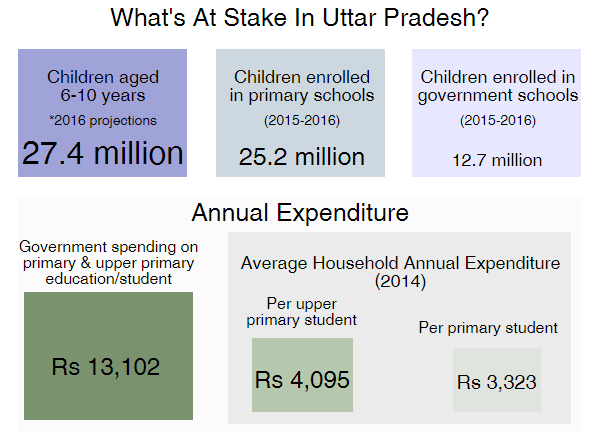

Like more than half (50.4%) of all primary school-age children in UP, Saidun attends a government primary school (providing free education to children between 6 and 14 years), and like many children in the state, she cannot read at grade level.

Even though residents in two districts of UP said education was important for the future of their children, only 2% of voters surveyed listed education as the most important issue during the ongoing state assembly elections, according to a FourthLion-IndiaSpend survey.

In conversations across the two districts, few villagers were willing to engage with the government system to improve the quality of education, in a state that accounts for 52 million or 21% of India’s child population between the ages of six and 15 years.

The low quality of education in the state (and dearth of jobs) puts India’s future workforce at risk and is reflected in UP’s high unemployment.

In 2015-16, more people per 1,000 were unemployed in UP (58), compared to the Indian average (37). Youth unemployment was especially high, with 148 for every 1,000 people between the ages of 18 and 29 years in UP unemployed, compared to the Indian average of 102, according to 2015-16 labour ministry data.

As many as 20% of voters surveyed said jobs were the most important issue this election year, according to a FourthLion-IndiaSpend survey. Between 2001 and 2011, over 5.8 million between the age of 20 and 29 years migrated from UP in search of jobs, but, for most of these migrants, low educational attainment likely resulted in low-paying jobs in the informal sector.

Source: Ministry of Human Resource Development, District Information System for Education, 2015-16, Economic & Political Weekly, National Sample Survey, June 2015

Parents and children don’t think they can change the education system

Though there is almost universal enrolment in primary schools in UP--25 million enrolled in grade I to V in 2015-16--learning is challenged by the quality of education and high absenteeism.

In 2016, about half (49.7%) of grade I students surveyed in households in UP could not read letters, while 44.3% could not recognise numbers up to nine, according to the Annual Status of Education Report, a citizen-led assessment of learning in rural India.

On average, only half the students of six schools in two districts were in class when IndiaSpend visited.

Parents in Mirzapur district said they recognised their children were not learning much in school, but that they did not think they could change the existing system either through elections or by meeting local teachers and officials.

“They don’t know how to count till 100 and don’t know the table of 20,” said Shyamnarayan Vishkarma, 38, about his three children in the Fattepur village government school.

Ahmed, Saidun’s father, said he visited the school twice and told teachers that he didn’t think his child was learning enough in school. The teachers told him that they were doing their job and teaching her, and that he as the ‘guardian’ of the child should also help out, he said.

“Our family was very poor. I enrolled in school but we wouldn’t study very hard and did other work too,” said Ahmed. “Aren’t teachers guardians too when children are in school?”

Iklakh Ahmed, second from the right, said he will move his daughter from the government school in Fattepur village, Mirzapur district, to a private school. “Children don’t learn much in the government school,” he said.

Teachers told IndiaSpend that low learning outcomes were mostly because of low attendance and little interest from parents to help their children at home.

“What should we say to education officials or candidates?” asked Ahmed, Saidun’s father. “No one cares or talks about it. If they come here, they ask for votes and then leave.”

“Citizens face constraints in influencing public services,” found a 2010 randomised evaluation of interventions to engage communities in education, conducted by researchers from the Abdul Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-Pal), a network of 146 professors trying to reduce poverty through evidence-based policy, and Pratham, a nongovernmental organisation.

Interventions that involve beneficiaries in improving public services have mixed results, the study further explained.

There were three interventions as part of the J-Pal study: The first facilitated meetings of villagers, teachers, and administrators, and disseminated information on the role of village education committees, a second also trained volunteers to administer literacy tests on children and prepare reports, and a third intervention trained volunteers to provide basic after-school reading classes to children.

Despite the fact that many parents attended meetings, and wanted to improve education levels, none of the three interventions significantly increased the village education committee or parents’ involvement in schools or improved school performance, the authors found. Children who were part of reading classes performed better than those who were not a part of the intervention.

“Parents may be too pessimistic about their ability to influence the system even if they are willing to take an active role, or parents may not be able to coordinate to exercise enough pressure to influence the system,” the study suggested.

“What will change if we ask for it?” asked 11th-grader Binita, 17, who rides 7 km through forest on her bicycle to a high school in Girijapuri, in the central UP district of Bahraich. “I can’t attend school regularly because sometimes there is work to do at home, at other times, there is no one to accompany me through the forest.”

Seventeen-year-old Binita, left, rides 7 km on her bicycle through forests in Katarniaghat sanctuary, in the central Uttar Pradesh district of Bahraich. She said a school near her house would help her attend school more often.

Further, several parents are illiterate--UP’s literacy rate or, the ability to read and write one’s own name, is 70%--and these parents say they don’t know how schools can be improved.

“I haven’t thought about how the school can be improved,” said Tukia Devi, a tribal living near the Bisunapur primary school in Bahraich district, and mother to a five-year old daughter. “I am illiterate, I don’t know what can be done.”

Easier to improve education opportunities outside the government system

The J-Pal study suggested there seemed to be a greater willingness of individuals to help improve the situation for other individuals, rather than undertake collective action to improve institutions and systems.

“I have thought of doing something for the children of the village,” said Bhondu Prasad, 32, who has taught in a private school, and is the husband of Bisunapur’s village head. He said he believed that helping students after school through “tuition classes” or by training older children to help younger ones could help children learn how to read.

Or “parents might react to the knowledge that learning outcomes in government schools are poor by moving children to private schools,” wrote Lindsay Read and Tamar Manuelyan Atinc in a January 2017 working paper by Brookings Institute on community interventions to improve education outcomes by using data.

In April, at the beginning of the new academic year, Ahmed, Saidun’s father, said he would move her to a private school, costing about Rs 400 a month. Ahmed is a driver, and earns between Rs 4,000 and Rs 10,000 a month, depending on the jobs he gets.

“Everyone wants the best for their children. Why will they send them to government schools?” said Navneet Kumar, 35, of Niyamatpur Kalan village, in Mirzapur district.

“Only those who don’t have money send their children to the government school,” said Shyamlal Kaushal, the head of Niyamatpur Kalan village in Mirzapur district. “Even government school teachers enrol their own children in private school,” he said.

Niyamatpur Kalan, a village in eastern Uttar Pradesh. The head of the village said only those who do not have money enrol their children in government schools because private schools are perceived to provide better education.

About half of all children (46.5%) in UP study in private primary schools--an increase of 80.6% from 2007, according to the District Information System for Education.

Source: District Information System for Education, 2015-16; Figures for grades I to V

What about those who cannot choose schools?

The move to private schools doesn’t help government schools, which are often the only option for the most disadvantaged, like Sibi Devi, a single mother of five, from Bharehta village in Mirzapur, and a daily wage labourer at a nearby brick kiln.

“Utna karenge jitni haisiyat hain,” said Sibi Devi, in Hindi. “I will do as much as my capacity permits.” Four of her children are enrolled in a government school. Her oldest, a 15-year-old daughter, studied in the government school until grade VIII, because school was free of cost, and now works at the brick kiln.

Children from grades I to V in Bharehta primary school, Mirzapur district. Parents in UP said government school teachers are not motivated enough to teach well, while teachers said students do not come regularly to school.

Similarly, in remote areas such as the Katarniaghat sanctuary in Bahraich district, along the Nepal border, inhabited mostly by poor Tharu tribals, not many private schools operate, making government schools the first, and sometimes the only option for parents.

There is wide variation between the proportion of children who study in private schools across districts, with 22.9% of children in Shrawasti in private schools compared to 74.1% in Gautam Buddh Nagar, according to the 2016 ASER report.

A 2014 study found that the learning gap between public and private schools would decrease if factors such as age, gender, number of siblings, education level of the parent and wealth were considered. The study suggested that children who study in private schools were more likely to have educated parents, have fewer siblings and thus receive more parental attention, and be part of families richer than those who study in government schools.

Source: Annual Status of Education Report, 2016

Party manifestos do not address major education failings

Even though manifestos of both the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Samajwadi Party (SP) mentioned education quality, they outlined few concrete steps to address failings at the school level. (The Bahujan Samaj Party, the third major party in the UP elections, had not released an election manifesto at the time of publishing.)

Neither the BJP nor the SP manifesto suggested solutions to either improve student attendance, which teachers laid out as one of the main issues, or to make teaching more effective, and motivate teachers on the job, an issue important to parents.

For instance, even though the name of the section on education in the BJP manifesto is “improvement in quality of the education sector”, it concentrated on inputs--free education, books, uniforms, teacher-student and classroom-student ratios.

The SP manifesto proposed a “mission”, which would include teacher training (but without details on how this would be different from what happens currently), and teacher evaluations, provision of education through technology, and creation of model schools, among other things. The SP, in its manifesto, provides an alternative to government school: Admission of children from poor families to private schools.

It in unclear whether the SP manifesto is suggesting a provision separate from India’s Right to Education Act, which reserves at least 25% of seats in private primary schools for children from economically weaker families in the neighbourhood.

Further, the challenges parents would face in driving improvements in education quality in government schools become apparent as one talks to local education officials.

For instance, children in the government primary school in Bisunpura village received some grade three books for the 2016-17 academic year in 2017, less than three months before the end of the school year, a student told IndiaSpend.

When asked about the delay in giving books, a relatively simple input when compared to, say, pedagogy, the basic education officer of Bahraich district, for about 20 minutes, explained a bureaucratic method of procuring and distributing books to each school and child, involving several different officers at all levels.

He said he could do little about the delay as the books were ordered by the state education department in Lucknow, the tender for which had been delayed this academic year because of legal issues.

Even when officials recognise that the major issue is learning levels, steps to change the status quo fall short. For instance, district officials in Mirzapur district told IndiaSpend that goals this year included teaching students basic reading, math and writing.

For that, officials would conduct random evaluations and check the level of students compared to a pre-decided goal set by the district, officials said. Teacher training would be a focus with more trainings, but there did not appear to be a major redesign of the training itself.

(Shah is a writer/editor with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________

“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”