66% Working Indians Earn Less Because Of Childhood Stunting, One Of World’s Worst Rates

Mumbai: Around two-thirds of the working population in India are earning 13% less because of stunting in childhood--being excessively short for their age--one of the world’s highest such reductions in per capita income, according to a new report released by the World Bank.

Children with stunted growth must endure adverse outcomes later in life: They suffer from impaired brain development, which leads to lower cognitive and socio-emotional skills and lower levels of educational attainment. The lack of these skills have led to 66% of the workforce earning less than it would otherwise have, one of the highest such proportions worldwide, said the World Bank report, released in August 2018.

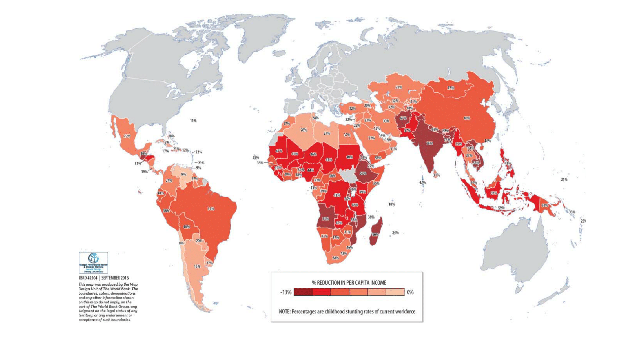

Indians, who live in one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, lost more income than people, on average, from Sub-Saharan African countries. The economic impact of stunting, however, was not limited to Asia and Africa, said the Bank, affecting as it did almost all continents in varying amounts.

The average reduction for South Asia was 10%, while that for North America was 2%. Middle East and North Africa do better, with a reduction of 4%, compared to Europe and Central Asia with a reduction of 5%.

Of the 140 countries analysed, only Afghanistan (67%) and Bangladesh (73%) surpassed India’s proportion (66%) of workers who were stunted as children.

Per Capita Impact on GDP of Childhood Stunting

The percentage of childhood stunting in India’s current working-age population, however, does not mirror the percentage of children currently stunted, given the gap between childhood and joining the workforce.

Over 26 years to 2014, the percentage of stunted Indian children under five has reduced from 62.7% to 38.7%, but one in three Indian children is still stunted.

Stunting reflects treatment of women, children

Countries poorer than India have handled stunting better. For example, Senegal, with a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) half of that of India’s, was able to reduce stunting in its children by half over 19 years to 2012.

Stunting is affected by a variety of socio-economic determinants, said experts.

“A lot has been written about the differences between India and sub-Saharan Africa,” said Purnima Menon, senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute, “Many parts of sub-Saharan Africa fare much better on many determinants, especially women’s status and sanitation. It isn’t just about the state of the economic development--it’s about how girls and women, who will become future mothers, are treated by society.”

Despite the varying socio-economic conditions, a nutrition-specific national programme could tackle stunting.

“Peru’s declines in stunting came about through a combination of social-transfer programmes targeted at the poorest parts of the country, along with health and nutrition interventions,” said Menon. “This has also been seen in other countries.”

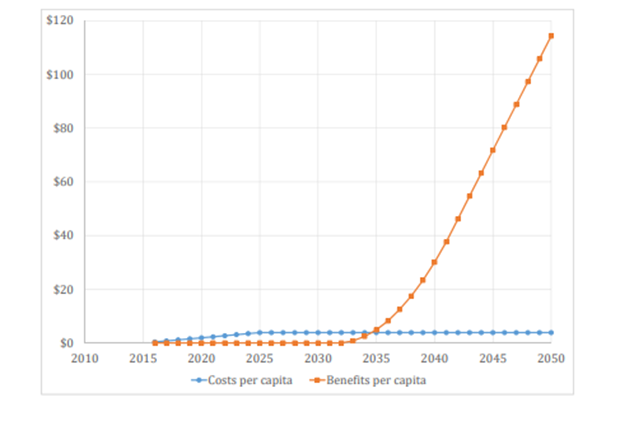

The World Bank report also calculated--using 10 interventions focussed mainly on maternal and neonatal health--that the returns on a national nutrition package outweigh the costs.

Estimated Impact Of A National Nutrition Package

Considering the lag between childhood and joining the workforce, the effects of a nutrition programme on the stunting rate among workers begins to show only 15 years after implementation, said the World Bank report. After the initial 15 years, the cost remains static, and the benefits from the programme continue to increase as more of the workforce begins to benefit.

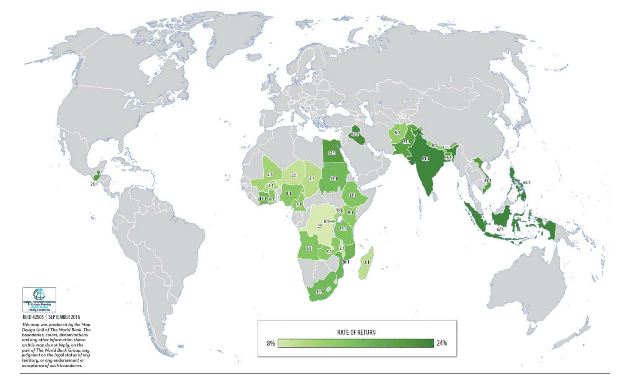

The average rate of return predicted for the programme was 17%, but for India the returns were forecast at 23%, with an economic benefit 81 times the cost.

Rate Of Return, By Region

While such a programme is useful, it is may not be enough.

“The antecedents of stunting in India lie in social inequity (women’s status and health, household wealth, access to services, etc.),” said Menon. “So, the nutrition strategy must fully embrace these aspects as well and not assume that a social movement focused on behaviour change and improvements in health services and ICDS [Integrated Child Development Services] and sanitation interventions will do it all.”

(Shreya Raman is a data analyst at IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.