Non-Communicable Diseases Rise In India, Poor States Still Grapple With Infectious Diseases

Students from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences conduct a community education programme in a Delhi slum. The Indian health system faces a dual risk: Non-communicable diseases such as heart disease are rising in the population, even as communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional diseases such as tuberculosis remain high.

As incomes rose over the last 26 years, India’s burden of disease shifted: More deaths in India (61.8%) in 2016 were due to non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, while in 1990 more deaths (53.6%) were due to communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional (CMMND) diseases, according to a recent study published in the medical journal Lancet.

The report, ‘India: Health of the Nation’s States, the India state level disease burden initiative’, is the first state-level disease burden and risk factors estimate by the Indian Council for Medical Research, the Public Health Foundation of India and the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation.

For the first time, a study estimated the key drivers of disease, disability, and premature death in all 29 states, many of which have populations the size of large countries, and include people from over 2000 different ethnic groups, per a press release from the Lancet. The research analysed 333 diseases and injuries and 84 risk factors for each state in India between 1990 and 2016, as part of the Global Burden of Disease study.

India’s health system faces a dual challenge--while the burden from diseases such as diarrhoea, lower respiratory infections, tuberculosis, and neonatal disorders has reduced, it still remains high. “At the same time, the contribution to health loss of non-communicable conditions such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes is rising,” noted the report.

In 1990, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) accounted for 37.9% of all deaths—causing about four in ten deaths in India. In 2016, the share of non-communicable diseases had risen up to 61.8%--causing six in ten deaths in India, an increase of 23.9 percentage points from 1990.

CMNND diseases--largely preventable and caused mostly due to poor sanitation and public health--decreased from 53.6% of all deaths in 1990 to 27.5% in 2016, a decrease of 26.1 percentage points, even as large interstate differences persist in the burden of disease.

Injuries increased from 8.5% of all deaths in 1990 to 10.7% in 2016, an increase of 2.2 percentage points.

There has also been an increase in life expectancy at birth--an indicator of overall health status of a country--from 58.3 years for males and 59.7 years for females in 1990 to 66.9 years for males and 70.3 years for females in 2016.

Poorer states still burdened by communicable, maternal, neonatal, nutritional diseases

There are wide variations between health indicators of different states. The eight under-developed states in the Empowered Action Group (EAG)--Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bihar-- and Assam and northeastern states--still had a high burden of infectious diseases.

More developed states such as Kerala, Goa and Tamil Nadu had a higher burden of noncommunicable diseases.

“For the first time, we have state specific comprehensive data that can help policymakers determine how to spend health budgets and which diseases to focus on, since even neighbouring states vary significantly in their disease profile,” said Professor Lalit Dandona, of the Gurugram-based Public Health Foundation of India, who led the study.

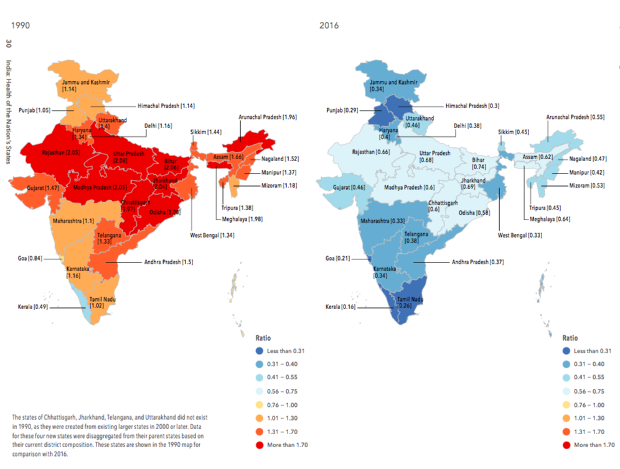

The variation between states is also reflected in the epidemiological transition ratio--the ratio of the number of Disability Affected Life Years (DALYS) in a population due to CMNNDs to the number of DALYs due to NCDs and injuries together. DALYS is a measure of both premature mortality and disability due to disease.

A ratio greater than one indicates a higher burden of CMNNDs while a ratio less than one indicates the opposite. The lower the ratio, the greater the contribution of NCDs and injuries to a state’s overall disease burden.

While the epidemiological transition ratio is 0.16 in Kerala, 0.21 in Goa and 0.26 in Tamil Nadu indicating high non-communicable disease burden, it is as high as 0.74 in Bihar and 0.69 in Jharkhand showing that infectious, maternal, nutritional diseases still affect many lives in these states.

The timing of the shift in the burden of disease from CNNMD’s to NCD’s varied widely between states and population sub groups, ranging from 1986 to 2010. For most of India, 2003 was the crossover year when NCDs exceeded CMNNDs, for North-East states it was 2005, for EAG, 2009.

Epidemiological Transition RatioOf Different States, 1990-2016

Source: India: Health of the Nation’s States 2016

Heart disease caused the most deaths in India in 2016

In 2016, the death rate from ischemic heart disease--the top cause of death in India--was twice as much as the next biggest cause of death--chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The other NCDs that caused the most deaths included stroke, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease.

Diarrhoeal diseases, lower respiratory infections, and tuberculosis were the leading CMNND causes of death, while road injuries and suicides were the leading causes of death under injuries.

The death rate from COPD was generally higher in the EAG states, with the highest rate of death from COPD in Rajasthan (111 per 100,000), five times that of Delhi (22 per 100,000).

The death rates from diarrhoeal diseases and tuberculosis were also higher in the EAG states. For example, the death rate from diarrhoeal diseases in Jharkhand was 120 (per 100,000 population) compared to 14 in Goa. The death rate from tuberculosis was 58 per 100,000 population in Uttar Pradesh compared to 8 in Kerala, the data show.

Even within poorer states, there is wide variation in the burden of different diseases. For instance, while diarrhoeal disease is a leading cause of death in Odisha (death rate of 120 per 100,000) for Rajasthan it is COPD (death rate of 111 per 100,000).

Source: India: Health of the Nation’s States 2016Note: EAG: Eight underdeveloped states that form the Empowered Action Group--Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Bihar

Rise of non-communicable diseases result of changing lifestyle, greater life expectancy

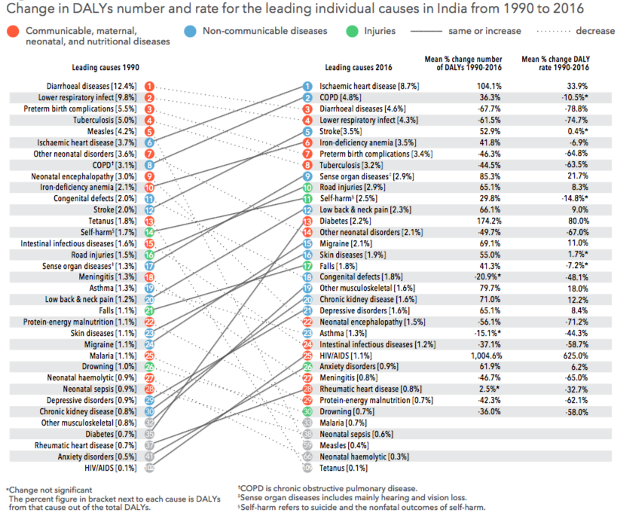

In 1990, diarrhoeal disease and lower respiratory infection were the top two causes of DALYs, but in 2016, the top two causes were ischemic heart disease and COPD, moving up from the sixth and eighth place, respectively. In 2016, the third and fourth most common cause of DALYs were diarrhoeal diseases and lower respiratory infection.

Conditions such as preterm birth complications, tuberculosis, and vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, also decreased--representing India’s achievement in ensuring more children survive during their first weeks of their life, said the report.

Diabetes moved from from the 35th place to the 13th. The number of DALYs caused by ischaemic heart disease rose by 104% from 19.7 million DALYs to 40.2 million DALYs between 1990 and 2016, while those caused by diabetes rose by 174% from 3.8 million DALYS to 10.4 million DALYs.

“These trends are indicative not just of a population that is increasing in age and therefore living long enough to develop and suffer from chronic diseases, but also of the impact of lifestyle changes that come with a rapidly industrialising, urbanising society--from changes in diet and activity levels to more traffic on the roads,” according to the report.

Iron deficiency anemia--which could lead to weakness, dizziness, pregnancy-related complications and lower cognitive function--was the only CNNMD that caused more DALYs in 2016 than in 1990: It was the third leading cause of DALYs in women and sixth for both men and women.

“The study shows us that the EAG states suffer from the dual burden of disease” said Dandona. “These states already have a high burden of chronic obstructive lung disease and are also seeing a rise of heart disease and diabetes, along with a persisting high incidence of infectious diseases. Unless we stop both the non-communicable and infectious diseases in these states, there is going to be a massive increase in their burden of disease.”

The contribution of injuries to the total disease burden has increased in most states since 1990, with the highest proportion of disease burden due to injuries in young adults.

Leading Causes Of DALYs, 1990-2016

India at most risk from child and maternal malnutrition

A risk factor is a cause of disease and injury, that could be potentially averted.

Even though the disease burden due to child and maternal malnutrition decreased since 1990s, it is the single largest risk factor for disease in India, since it increases the risk of neonatal disorders and nutritional deficiencies as well as diarrhoea, lower respiratory infections, and other common infections--accounting for 15% of India’s total disease burden.

Child and maternal malnutrition pose the highest risk in EAG states and Assam, and this risk is more to females than males.

The disease burden due to child and maternal malnutrition in India was 12 times higher per person than in China in 2016. Kerala had the lowest burden due to this risk among Indian states, but even this was 2.7 times higher per person than in China, per the report.

Air pollution was the second leading risk factor for Indians. Outdoor air pollution caused 6.4% of India’s total DALYs in 2016, while household air pollution caused 4.8%. Together, they contribute to India’s burden of cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and lower respiratory infections.

Behavioural and metabolic risk factors like dietary risks, which include diets low in fruit, vegetables, and whole grains, but high in salt and fat, were India’s third leading risk factor, followed by high blood pressure and high blood sugar.

The disease burden due to unsafe water and sanitation reduced significantly in India, from the second leading risk factor in 1990 to the seventh in 2016. Still, this burden remains high in the EAG states and Assam, and is still 40 times higher per person in India than in China.

“The rise in India’s economic fortunes and its aspiration to progress to the same level as its neighbour, China, is something of an embarrassment, given how improvements to health trail so far behind. Until the federal government in India takes health as seriously as many other nations do, India will not fulfil either its national or global potential,” said a Lancet editorial that was published alongside the study. It added that it was disappointing that Prime Minister Modi pledged 2.5% of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) to health when the global average investment in healthcare was 6% of GDP.

(Yadavar is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.