Ongoing Crisis May Push Adolescent Girls Into Early Marriage Or Work

New Delhi: While 15-year-old Bhavani from Dindigul district in Tamil Nadu faces the prospect of having to drop out of school to work in a mill to help feed her family, across the country in Bulandshahr in western Uttar Pradesh, 17-year-old Anu’s life is also being turned upside down by the extended nationwide lockdown to contain COVID-19.

Anu’s days are largely filled with household and farm chores, her access to e-learning is poor, her meals are far less nutritious than those she received in her government school, and her parents cannot afford to buy her sanitary pads.

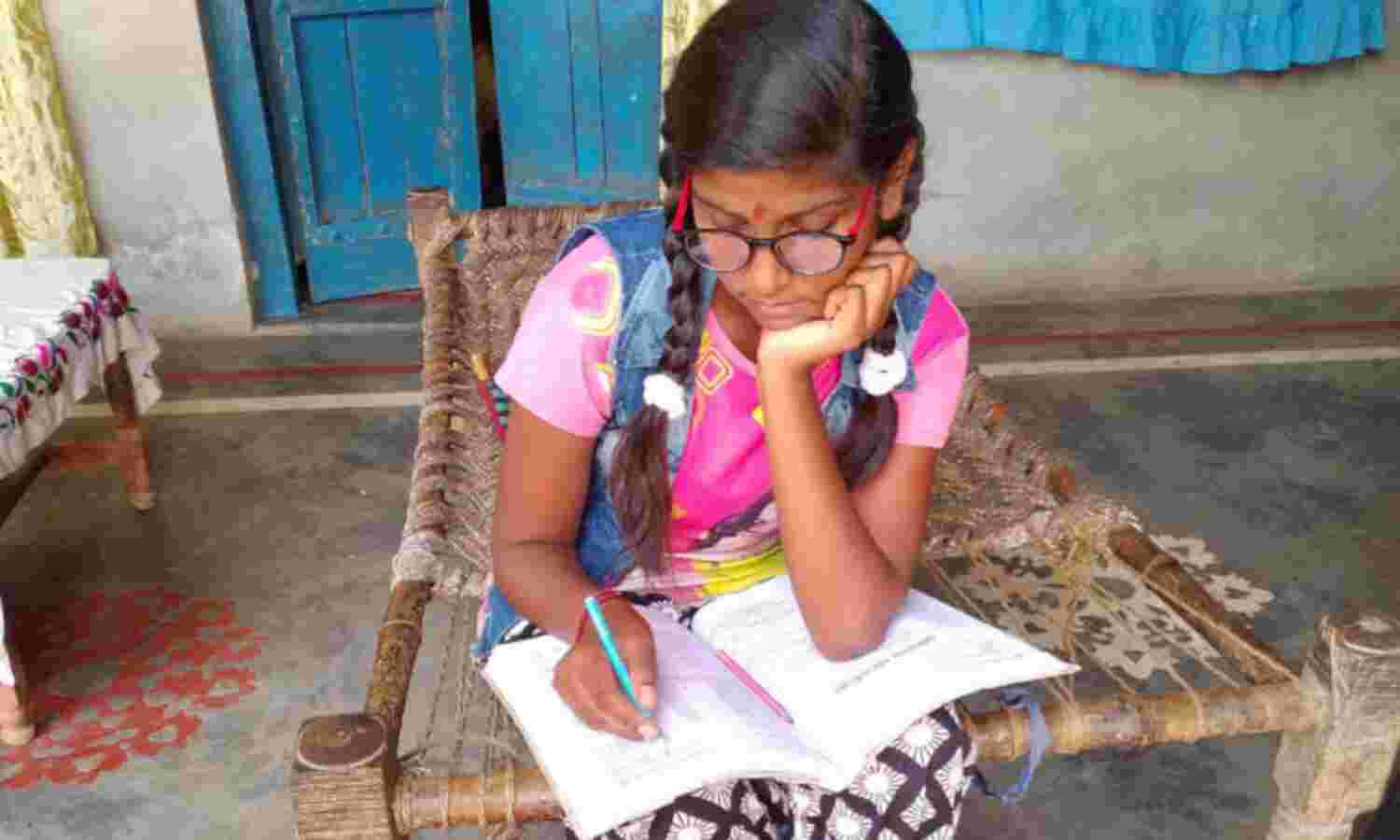

Bhavani and Anu, participating in a rapid survey conducted by Praxis India, a Delhi-based non-profit, on May 20, 2020, shed light on a little-noticed aspect of the pandemic: its worrying impact on the health, education and future prospects of adolescent schoolgirls.

The survey, interviewing 290 adolescent girls from Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, found that 36% were getting less food than before the lockdown (7% were even going without food on some days), 70% lacked access to sanitary pads, and 40% could not attend online classes.

But, looking beyond the lockdown, Anu, a 12th standard student from Barauli village whose favourite subject is English, told IndiaSpend in an interview: “Many girls are having their dreams broken in the lockdown, they will never be able to study, their lives will be ruined after this.” She used to walk to school at 7 a.m. every morning, and returned only at 5 p.m--her day there packed with classes on different subjects, games and extracurricular activities. Her school has been shut since March 24, 2020.

Meanwhile, her 19-year-old sister was being hurriedly married off during the lockdown, she said, “because the marriage will be less expensive now, and she no longer has the excuse that she has to go to school”. Her sister wanted to pursue a master’s and become a teacher.

Girls affected more than boys

Experts emphasise that girls are worse affected than boys when a family faces huge setbacks and income losses, as millions of poor Indian families are currently, due to the surging pandemic, lockdown and economic downturn. Apart from losing access to nutritious food, sanitary pads and schooling during the lockdown, girls stand at a higher risk now of being pushed into early marriage and child labour, and being trafficked.

Almost half of Indian adolescents are girls, around 120 million 10-to-19 year olds. While the gap between boys and girls in school enrollment and completion is narrowing, completion of secondary school remains elusive for girls, said a policy brief published by Centre for Catalysing Change, India, in September 2019.

“Brothers usually get phones, medicine or food before their sisters, and get more than their sisters do,” said Renuka, a gender rights activist with Pardada Pardadi Educational Society (PPES), Uttar Pradesh, who uses only one name. “The moment a family’s income gets impacted by a calamity, girls are the first to bear its brunt, they are always thought of as a burden and not an asset so they are the lowest priority,” she told IndiaSpend.

“Adolescent girls are particularly vulnerable,” warned UNICEF in a paper developed with the crisis-action NGO International Rescue Committee, in response to the pandemic. It said studies of past disease outbreaks had shown that without targeted intervention, COVID-19 would “heighten pre-existing risks of gender-based violence (GBV) against girls, stymie their social, economic and educational development, and threaten their sexual reproductive health”.

It called for providing dignity/hygiene kits and learning and recreational kits to adolescent girls, targeting parents on the benefits of sending girls back to school after COVID-19, and, keeping in mind girls’ lack of digital access, finding ways to communicate to them vital information on health and GBV.

Girls locked out of nutrition

Before the lockdown, Anu had her breakfast and lunch at school, and usually ate leftovers or nothing at all after returning from school. Now, she eats mostly rice with chutney, “which only gives us carbohydrates and no protein”, she pointed out. Things are much the same with Moni, a 17-year-old from Anupshehr village in Bulandshahr district, who took her 12th standard exams this year: rice has replaced varied midday school meals that consisted of porridge, pulses, vegetables and often fruits.

“My family cannot afford green vegetables when they are not able to earn anything,” Moni, who does not use a surname, told IndiaSpend. Moni has four sisters and two brothers. Her father, the sole bread-winner, who worked as tailor in Delhi, has lost his job and spent all his savings trying to get back home during the lockdown.

Overall, the Praxis survey showed that the loss of access to school midday meals has had a significant impact, with 36% of the respondents reporting that they were getting lesser and poorer quality food after schools had closed. All 24 respondents in West Bengal reported a decrease in food intake, with as many as 17 saying there were days when they got no food. Of the 215 respondents in Uttar Pradesh, 27% said they were getting less food now, as did 41% of the 51 in Tamil Nadu.

Anu’s plate of lunch with rice and chutney, which is mostly what the family can manage with the free rations they are receiving during the lockdown. (Photograph shared by Anu.)

The adolescent girls, who usually get health supplements such as vitamins and iron-folic acid tablets and take-home ration (THR) through the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) or on Village Health and Nutrition Days, said this had stopped during the lockdown, “Every Friday we were given vitamin tablets, but now we are not getting anything,” said V. Karthika, 17, from Ayyapatti village in Dindigul, Tamil Nadu.

When asked for suggestions, the girls told Praxis that they wanted door-to-door delivery of iron tablets and sanitary napkins through the ICDS.

“Inadequate nutrition during adolescence can have serious consequences throughout the reproductive years of life and beyond,” warned a 2012 study on adolescent girls published in the Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. As many as 51.8% of teenage Indian girls are anaemic, IndiaSpend reported in October 2018 based on a survey by the Naandi Foundation, which works with adolescent girls.

Experts emphasise that malnourished and anaemic adolescent girls give birth to underweight children, especially in situations of child marriage and underage pregnancy. “If this child is a girl, she grows into a malnourished, stunted adolescent mother and the cycle continues,” said Yogendra Ghorpade, field coordinator at ‘Towards Advocacy Networking and Development Action’ (TANDA), a project at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. Around 27% of girls in the 20-24 year age group are married before the age of 18 years and 7.9% aged 15 to 19 are already mothers, according to the National Family Health Survey, 2015-16.

COVID-19 could reverse gains in girls’ education

“I feel if the lockdown did not happen, some young girls I know might have continued their schooling,” said Moni from Bulandshahr, who uses her father’s phone to sometimes attend e-classes. The phone has a very small screen, little storage and keeps lagging. She fears they may not go back now.

“We are looking at a huge risk of thousands of girls completely dropping out of the education system,” said Renuka from PPES. “Schools are a secured space; without them, these girls are more vulnerable to sexual abuse. If a family doesn’t have enough money, girls are the first to be sold, sent into work, exploited, often married off to much older men.”

Moni, 17, from Bulandshahr, Uttar Pradesh, says that with her school being shut during the lockdown, she has to perform all household chores like cleaning and cooking, which leaves her with little time to study. (Photo shared by Moni)

Access to education during the lockdown is a challenge because e-classes require infrastructure not widely available--the 75th National Sample Survey (NSS) 2017-18 indicated that 89.3% of Indian households did not have a computer and 76.2% did not have Internet access.

The situation is even worse for adolescent girls, with differential access to phones. “The boys get mobile phones but girls never do; parents fear that a girl might run away with someone or get “spoilt” if she’s given a phone,” Moni told IndiaSpend. Her younger brother was given a phone when he was 13, while she did not fight for one, not wanting to add to her family’s financial burden.

UNICEF, in its paper cited above, said that while “mobile phone ownership and access has increased globally, women are still less likely than men to own a phone and it is estimated that there are 443 million “unconnected” adult women in the world”.

Apart from 40% girls not able to attend e-classes at all, another 9% were able to attend only sometimes, the Praxis survey found.

“School closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to millions of more girls dropping out before they complete their education, especially girls living in poverty, with a disability or living in rural isolated places,” the UNICEF paper said. Gains made in increasing girls’ access to education could be reversed, it stressed.

When Praxis asked for suggestions, the respondents asked for classes they can access through TV sets rather than phones or computers, for educational loans, and for their schools to set up peer learning groups.

Black marketed sanitary pads

The high cost and embarrassment involved in procuring sanitary pads leads girls to rely on their schools to provide these. School closure has curtailed their access to sanitary pads, with 204 of 290 respondents in the Praxis survey saying they were unable to access pads and another eight saying they managed to get access sometimes.

Those interviewed complained about the embarrassment of using cloth, which is less absorbent and stains their clothes. Sanitary pads were selling at a higher price, Anu said: “A Rs 30 packet costs Rs 50, there is no way we can afford this.”

Since, in the absence of sanitary pads, girls may resort to using dirty cloth--and even mud or leaves--raising the risk of reproductive tract infections, there is a great need for sanitary pads to be distributed through the PDS, said Renuka from PPES. “It should not be one packet for the entire family but a minimum of two packets per menstruating person,” she stressed.

Child marriage, labour and trafficking

The family of Bhavani, who hails from Kurumbapatti village in Dindigul district, Tamil Nadu, is deep in debt, the Praxis survey found. Her parents had earlier taken loans to cover the family’s medical expenses and later to buy rations during the lockdown to feed their family of five, and had now lost their jobs. Therefore, they expected her to drop out of school and contribute to the family’s income.

With mounting debt and job losses due to the pandemic and lockdown, thousands of girls may drop out of schools, with families wanting their daughters to work and generate income rather than continue their education, said Renuka from PPES. “Borrowing has escalated by 25% in the country and a girl is impacted because she is pledged as labour or married off,” she said.

Jayashree Mondal, 19, a child rights activist from Panchghara village, South 24 Parganas district, West Bengal, fears that situations may increasingly arise in which girls are sent out to work in cities without verifying whether their workplaces are safe for them, and marriages may also similarly be arranged without checking on the credentials of the groom, making girls vulnerable to trafficking. “Marriages are being fixed in increasing numbers in villages,” she told IndiaSpend.

The UNICEF report also emphasised that adolescent girls are more vulnerable to sexual exploitation, harassment and gender-based violence during the pandemic, with dire economic conditions providing “ample opportunities for perpetrators to exploit adolescent girls’ need to attain basic necessities to survive”. It said: “Multiple accounts have been documented of burial teams, drivers, frontline health workers and others; demanding sex in exchange for food and vaccines.”

(Tiwari is a principal correspondent with IndiaSpend.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.