Where The Government’s Flagship Schemes Really Fail

In 2005, the Indian Government launched a nation-wide programme to ensure safe motherhood. Christened Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), it attempted to ensure proper facilities for maternal and newborn care.

While the scheme has now touched nearly 50 million women, its seeming success in outreach has also highlighted the problems (and some very fundamental) in the nature of such schemes and their ultimate outcome.

For instance, the fact that many women are opting to deliver children in hospitals is putting tremendous strain on hospital resources. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, the majority of women (59%) are discharged within 12 hours, thanks to lack of infrastructure, particularly electricity, beds and other essential amenities.

And then there is the problem of awareness. Facilities like free ambulance service (provided to ensure safe delivery) are available but are used by very few beneficiaries because they don’t know it exists.

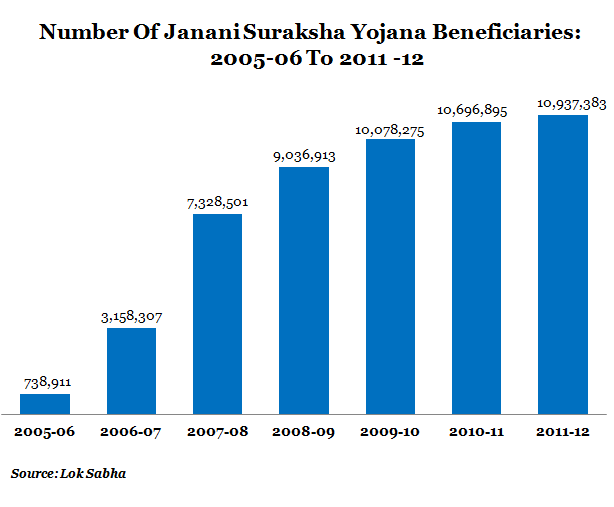

So, let us start with the basic numbers. As we reported earlier, JSY has so far reached over 50 million pregnant women. Table 1 shows the increase in the number of beneficiaries from 2005 to June 2012.

Figure 1

The number of deliveries in hospitals, primary health centres and community health centre has been increasing for the last six years, and nearly 11 million mothers utilised the facilities in 2011-12. At one level, that’s an encouraging sign since India has been struggling to achieve its Millennium Development Goal (MDG)of reducing maternal mortality by three-quarters.

Around 56,000 women die every year due to pregnancy-related complications, according to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. And the national maternal mortality ratio (defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) is 212 in 2007-08.

Now, let’s look at the key problems faced by the scheme, which in some ways are symptomatic of other large-sweep programmes. To do this, we’ve used both Government surveys as well as sample studies carried out by the Population Council, Accountability Initiative and National Health Systems Resource Centre (NHSRC).

Lack of Awareness

While studies like the Population Council report and the study by National Health Systems Resource Centre show that awareness about JSY is almost universal, there are certain aspects of the scheme where the beneficiaries do not have complete information.

1) For example, most women from below poverty line (BPL) families or from SC/ST categories had 'incomplete’ knowledge about the scheme.For example, SC/ST women not going to hospitals is due to lack of awareness of the benefits of the scheme like free ambulance service.

2) Awareness regarding the cash transfer is also quite low - only 66% urban women and 32% rural women knew they were entitled to receive Rs 1,000 and Rs 1,400, respectively, under the scheme.

3) Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) or an equivalent worker should be working as a basic health provider in the village as part of JSY. Such workers get incentives in low-performing states for providing essential support services.

But awareness of ASHAs was limited: only 46%women had heard of ASHAs. Rural areas fared better when it came to awareness on ASHAs -52% -against urban areas with only 26%. But urban women are better informed about the duties of ASHAs.

B] Quality of Services Provided

JSY has increased the number of institutional deliveries to 44% (according to the Population Council report), which is much better than 23% reported by the district level health survey (DLHS-3, 2007-08) conducted by the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare although the data for the population council study is also not very recent.

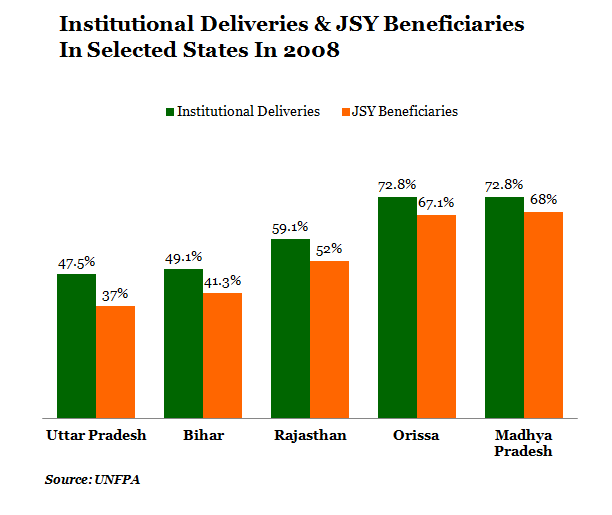

The chart below shows the number of institutional deliveries (in 2008 as no recent data is available) and the number of deliveries under JSY. We can see that Orissa and MP registered the highest number of institutional deliveries with 73% each. Out of that, 68% cases were that of JSY beneficiaries.

Figure 2

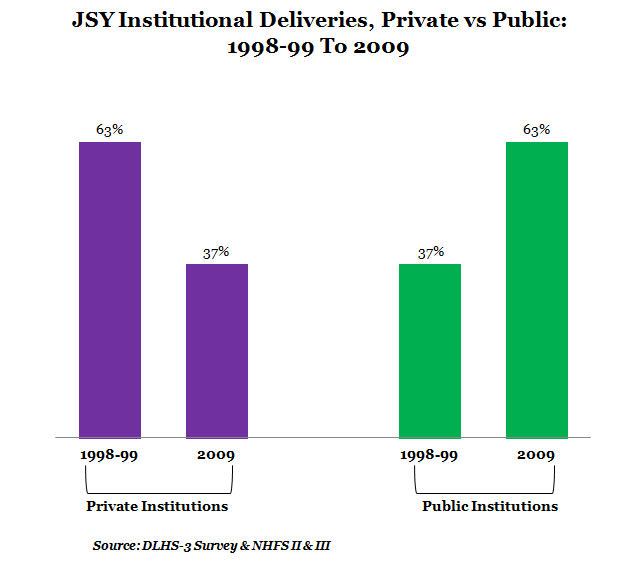

An interesting change is that while institutional deliveries in private hospitals declined from 63% in 1998-99 to 37% in 2009, it increased at public facilities from 37% to 63%, possibly due to the JSY push.

Figure 3

A major reason, of course, is that the beneficiaries have to opt for government hospitals or health centres to get the benefits of the programme. A more critical reason cited by experts is that private hospitals are not equipped to handle critical cases.

Although a positive development, it has increased the pressure on government health facilities. The DLHS-3 facility survey shows that more than half of the primary health care centres (PHCs) across the country have less than four beds or a functional operation theater. Very few PHCs (12%) have an electricity connection and even fewer are equipped to provide EmOC (emergency obstetric care).

In about 25% cases, the first examination of the expectant mother after reaching the facility was delayed considerably. Additionally,according to the Population Council report, the drug oxytocin was used indiscriminately in Uttar Pradesh (about 79% cases) to increase labor pain, and in 57% cases, pressure was applied on the abdomen to hasten the delivery, leading to high incidence of birth asphyxia, which may be contributing to still birth.

A study conducted by Accountability Initiative, a Delhi-based think-tank that tracks Government programmes, found that about 67% women reported that ASHAs stayed with them at the facility during birth.

The highest proportion was in Sundargarh (96%) and Hardoi (82%), and the lowest in Udaipur (30%), Rajgarh (35%) and Bhilwara (37%).Some of the reasons highlighted for the reluctance on ASHAs’ part were access to toilet facilities and no provision for food.

A post-partum visit by ASHAs are very essential for ensuring the safety of child and mother as most women (more than 50%) stay in hospitals for only 24 hours instead of the 48 hours recommend by the scheme. The Accountability Initiative study conducted in Rajasthan shows that only 14% women were visited by ASHAs at home while the national number was 60%.

C] Other irregularities

The survey conducted by the Population Council found that while all the women in their sample were eligible for JSY,only 46% had benefited from it. Additionally, women who had delivered at a young age (less than 18 years) and at ages 30–34 were less likely than others to have received the cash benefit (40–41% versus 44–51%).

Almost all studies showthatbeneficiaries from the minority communities had not received either a visit from ASHAs or the cash incentive… for example, the NHRSC study found that 63% women who deliver at home are more likely to be SC/ST, belong to the BPL category, and more likely to be non-literate or primary school drop outs.

Cash transfers:While the Population Council data shows that only 35% of Muslim women received the cash incentive, nearly half of the Hindu women received cash benefits. The conditions were slightly better in the urban areas.

According to a survey published by the Journal of Family Welfare, around 79% had received the full incentive of Rs 1,400; about 18% did not receive any incentive money and 4% received less than the recommended amount (Rs 250-750).

Family members, friends and neighbours (45%), followed by auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs) and medical officers, motivated women to seek JSY benefits.

Other schemes not utilised: Beneficiaries were generally unaware of schemes like the 108 ambulance service and special nutritional supplementation programme. Just 5% women had used the 108 ambulance service to go to a health facility for delivery, and hardly any had received a voucher for special nutritional supplements in the form of five kilograms of ghee.

Transport: The Population Council study shows that only 56% knew about the existence of the transport or ambulance facilities and that transport arrangement were to be made by ASHAs. 82% respondents reported that family members made the travel arrangements while 16% said the arrangements were made by ASHAs.

Conclusion

So, Janani Suraksha Yojana has increased awareness among beneficiaries about maternal health (both pre- and ante-natal) and newborn care. For example, 87% beneficiaries knew about regular ante-natal check-ups and 40% beneficiaries (compared to 32% of non-beneficiaries) were better informed about the essential preparations required for a safe delivery.

Beneficiaries were also aware of various vaccinations for the newborns and nutrition… this has led to many beneficiaries using institutional services during their next child birth.

This shows that with better awareness, along with strengthening of the available infrastructure and increasing capacity of the public health infrastructure, JSY can be more effective in ensuring maternal and newborn health.

It’s equally clear that awareness and understanding is a significant challenge when it comes to rolling out large flagship schemes in a manner that the benefits of the scheme reaches those it’s meant to.