Nobel Reminds India Of Its 60 Million Child Slaves

More than 80,000 Indian children have been freed from various form of slavery and labour and reintegrated into Indian society, thanks to the efforts of Kailash Satyarthi, 60, the electronics engineer who won the Nobel peace prize on Friday.

Yet, what he has achieved is a proverbial drop in the ocean.

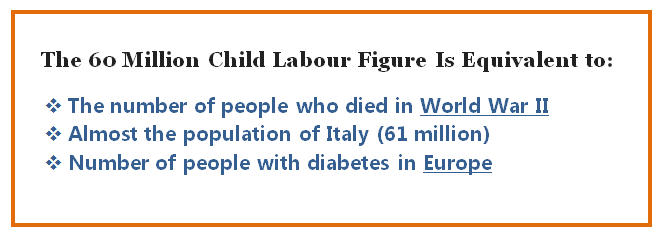

Admirable as Satyarthi's efforts, and those of his organisation, Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), or Save Childhood Movement, have been, the prize is a reminder of a situation that Indians prefer to ignore: the existence of about 60 million child slaves in India, the highest number of any country.

Satyarthi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 2014 along with Pakistan’s Malala Yousafzai “for their struggle against the suppression of children and young people and for the right of all children to education”.

Satyarthi, who started BBA in 1983, became the fifth Indian to win a Nobel prize, following Amartya Sen (1998, Economics), Mother Teresa (Peace), C V Raman (Physics) and Rabindranath Tagore (Literature).

In this interview to the BBC in Februrary, Satyarthi laid the blame for India's legions of child slaves at the doorstep of the emerging middle class.

"This is the most ironical part of India's growth. The middle classes are demanding cheap, docile labour," he said. "The cheapest and most vulnerable workforce is children - girls in particular. So the demand for cheap labour is contributing to trafficking of children from remote parts of India to big cities."

Satyarthi, in a column written in 2011, had argued that the exploitation of children was generating Rs 1.2 lakh crore ($20 billion) in unaccounted money for Indian employers:

“All the work that is done by child labourers and the income thus generated goes unaccounted for. Studies show that 60 million children work for approximately 200 days a year at an average cost of Rs 15 per child per day. This amounts to Rs 18,000 crore in one year. Now, these 60 million child labourers, when substituted with 60 million adult labourers, would earn Rs 1.38 trillion at a minimal rate of an average floor wage of Rs 115 per day per labourer for 200 days. This difference in the total earnings works out to Rs 1.2 trillion. This straight profit of Rs 1.2 trillion is a significant loss to the economy. The employer(s) should have legally and ideally paid this sum to the worker(s), but the employer(s) instead choose to employ docile, underpaid and overworked child labourers.”

The International labour Organization (ILO) defines child labour as work that deprives children of their childhood, their potential and their dignity, work harmful to physical and mental development.

Child labour is a pernicious problem in India. Children work in a variety of industries, from washing plates in roadside eateries to working--and dying--early in unregulated factories.

IndiaSpend in an earlier report, looked at child labour statistics across states in India and the hazardous industries that employ children. The incidence of child labour has dropped significantly in India, but it continues to be the highest in the world.

Data (from the National Sample Survey Organisation for 2009-2010) now puts the number of working children at 4.9 million, a 60% reduction since 2001; the figure is considered a major underestimate since millions of children are not recorded in official surveys and work in industries not regarded as hazardous, which is not illegal.

Indian laws only say that those below 14 years of age cannot be employed in "hazardous" industries. A bill, the Child and Adolescent Labor (Prohibition and Regulation) Bill, prohibiting the employment of children below 14 altogether, was introduced in Parliament in 2012, but has not yet been passed.

The major occupations involving child labour are pan, bidi and cigarettes (21%), construction (17%), and spinning & weaving (11%), which qualify as hazardous processes/occupations. Domestic workers constitute 15% of the total child workers.

Several accounts intermittently spotlight the horrors of child labour. One report, released earlier this year, was one of the largest ever investigations into child slavery in India’s handmade-carpet sector. It probed 172 companies, many whom sell their carpets to US chains, across nine Indian states, documenting bonded labour, human trafficking and forced labour.

"The working conditions uncovered were nothing short of subhuman," the report, written by Siddharth Kara, Fellow with the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights and Adjunct Lecturer on Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. "Factories and shacks were cramped, filthy, unbearably hot … filled with stagnant and dust-filled air, and contaminated with grime and mold. Some sites were so filthy, pungent, and dangerous that the researchers were afraid to enter due to the risk to their safety.”

Satyarthi's award should renew a focus on child labour. Shireen Vakeel Miller, advocacy director with NGO Save the Children, told India Abroad News Service: "This event will bring into the spotlight the problem of child labour in India."

The Nobel Prize "should be an inspiration for Indian children, millions of whom are still stuck in child labour", she said: "India now needs to focus on a complete ban on child labour in all forms."