Can A Drought Kill Your Political Chances?

| Highlights: * Andhra Pradesh & Karnataka, both drought affected states voted against the respective ruling parties in elections following droughts * Drought does not seem to be affecting the ruling parties in states like Orissa and Maharashtra * States like Gujarat and Rajasthan show partial correlation as they have voted against the ruling parties during one drought but voted for the ruling party for another drought |

It’s been whispered sometimes that a party in power lost the elections to drought. And that if the rains were in time and harvest bountiful, the grateful voters would have returned the ruling party with as much gusto as they did the first time, or earlier.

Is there any truth in these whispers? We don’t claim to know and this is a bit of a shot in the dark actually. And yet, it’s something to ponder about, at least in states like Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. So, we looked at the two sets of data that we could find of drought and electoral outcomes. And then pretty much stepped back.

What is a drought? The India Meteorological Department (IMD) defines meteorological drought based on rainfall deficiency (SW monsoon, June-September) as a) moderate and (b) severe based on rainfall deficiency, i.e. 26 to 50% and more than 50%, respectively.

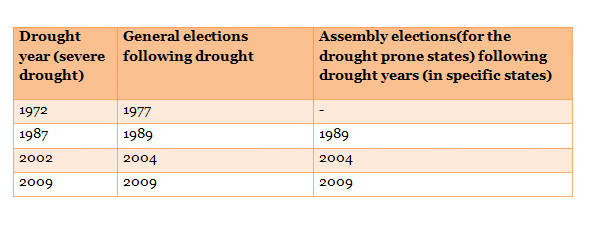

Table 1

Source: Indian Agricultural Statistics Research Institute, Election Commission Of India

The states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Gujarat and Rajasthan are some of the drought-affected states in the country. We first look at state assembly elections for the drought-prone states. We also include the normal election year where there was no drought declared. Most states did have elections in 2009 but the elections were held before drought was declared.

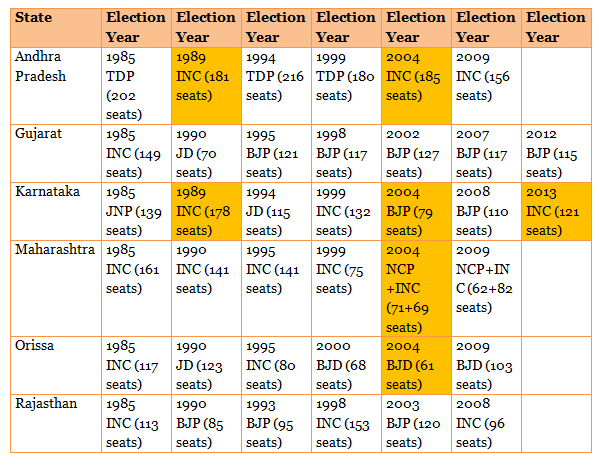

The table below shows the elections held in drought years (which have been marked in yellow) and non-drought year elections (which have not been coloured).

Table 2

Correlation: Electoral outcomes in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka seem to be affected by drought. Both states voted against the respective ruling parties in elections following one.

In Andhra Pradesh, the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) lost the elections in both 1989 and 2004. Similarly, in Karnataka, the ruling Janata Party (JNP) lost the 1989 elections, making way for the Congress to take over the state assembly.

In 2004, the ruling Congress lost the elections, making way for the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) to form the government in the state. The pattern has continued in Karnataka when the ruling BJP was voted out of power by the people in the most recent elections (2013). The year 2013 was declared as a drought year.

No Correlation: In states like Odisha and Maharashtra, drought does not seem to be affecting the fate of the ruling parties. In Maharashtra, the Indian National Congress (INC) lost 6 seats in the 2004 assembly elections that were held after drought was declared in the state in 2002.

It could, however, be said that the share of seats of the ruling party declines in elections following the drought year. For e.g., like Congress in Maharashtra, Biju Janata Dal (BJD) lost 7 seats in 2004 in Orissa in the polls held after the 2002 drought. Whether that had anything to do with the drought or local and regional factors is a separate study, of course.

Partial Correlation:In the 1990 elections (held right after the drought of 1989), the ruling parties lost the elections in Gujarat and Rajasthan. Gujarat, which was under a Congress government, voted for Janata Dal. Similarly, Rajasthan voted the Congress out of power by voting for BJP.

So, there is some correlation between drought and election outcomes in some states, for e.g. Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka… but many other factors like the overall economy, anti-incumbency and corruption scandals could also be major factors in deciding the poll results. And, of course, the relative agrarian sway.