Indian Elections: Debunking The Debunked Myths

"Survey shatters 5 Indian election myths" read a Financial Times headline in its characteristically emphatic style. The motivation for the headline was a survey carried out by the Centre for Advanced Studies of India at the University of Pennsylvania and Carnegie Endowment that presumably busted some purported myths based on voter surveys and data analysis. After listening to the authors of this survey in Mumbai last Friday, I left perplexed both about the myths and the shattering of them. Let's consider some of them.

"Survey shatters 5 Indian election myths" read a Financial Times headline in its characteristically emphatic style. The motivation for the headline was a survey carried out by the Centre for Advanced Studies of India at the University of Pennsylvania and Carnegie Endowment that presumably busted some purported myths based on voter surveys and data analysis. After listening to the authors of this survey in Mumbai last Friday, I left perplexed both about the myths and the shattering of them. Let's consider some of them.

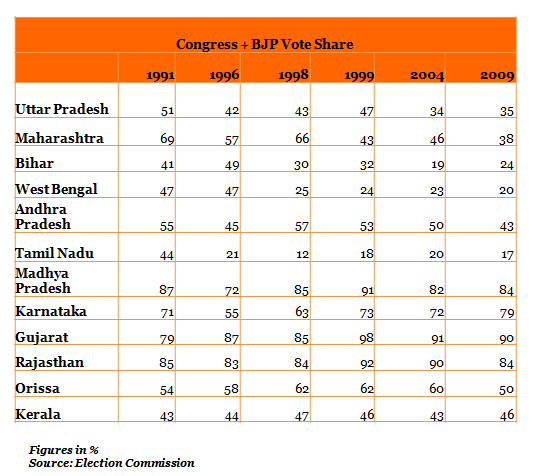

Regionalism is not on the rise; if anything, India is moving more towards a two-party system: This was the first pronunciation by the authors of this study. This conclusion was apparently based on a vote share analysis of the two national parties - the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress over a period of time, which showed that the combined vote share of the two parties remains constant or even increases marginally over time.

Having analysed past electoral data fairly extensively, I felt there was something amiss because this was contrary to what most of us (the small, inconsequential breed of electoral data analysts) had observed. My intuition told me that even if the vote share data were accurate, it probably ignores the effect of a very unique notion of pre-poll alliances in the Indian electoral landscape. This analysis shows how neither is regionalism, as defined by vote share of regional parties, waning nor is India moving towards a two-party system similar to most other Western democracies, keeping true to its diverse federalism.

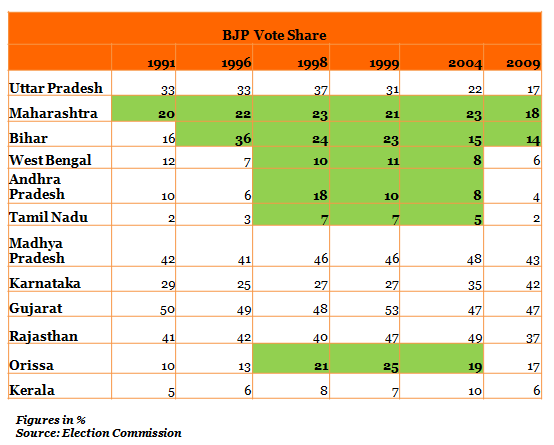

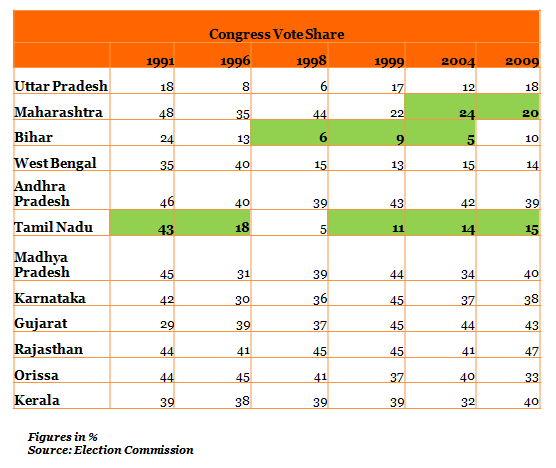

The 12 largest states accounted for nearly 90 per cent of all Lok Sabha seats until 1999 (until the break-up of big states), and currently account for 82 per cent of all seats. The tables above show vote shares of the two national parties - the Congress and BJP - in the last six Lok Sabha elections for each of the 12 states. The cells highlighted in bold indicate that the national party had a pre-poll alliance with a regional party in that election.

1. Of the 144 instances (12 states x six elections x two national parties), national party vote share may be over-estimated in 33 cases (23 per cent) due to the partnership with a regional party. In other words, without the alliance with a regional party, the national party's vote share can fall because otherwise, there would be no need for an alliance.

2. The BJP and Shiv Sena in Maharashtra (the second-largest state) are inextricably tied to each other and have fought all six elections together. This dependence on regional parties and the spawning of new regional parties such as the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena, which played spoiler by stealing vote share from the national alliances in at least 11 constituencies in the 2009 elections, only underlines the argument for growing regionalism.

3. In West Bengal, the third-largest state, it is evident from the table that when the BJP ties up with Mamata Banerjee's Trinamool Congress (TMC), its vote share rises as it did in 1998, 1999 and 2004. When the alliance breaks off in 2009, the BJP's vote share drops. So, merely counting a national party's vote share without analysing the impact of pre-poll alliances can lead to misleading conclusions.

4. In the southern states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, the impact of pre-poll alliances with regional parties is dramatic. The only time that the Congress fought alone in Tamil Nadu in 1998, its vote share dropped to five per cent versus the 15 to 20 per cent vote share it garnered when it was in an alliance with either the DMK or the AIADMK. Similarly, when the BJP is in alliance with the Telugu Desam Party in Andhra Pradesh, its vote share jumps to 10 to 18 per cent, otherwise it is in the four to 10 per cent range.

5. Similarly, in Odisha, an alliance with the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) props up the BJP's vote share to 19 to 25 per cent, otherwise it is around 10 to 17 per cent.

The chart above shows vote shares of the two national parties in these 12 states over the past six Lok Sabha elections, before negating the alliance impact and after. The negation of alliance impact is not an exact science and is a mere extrapolation exercise. But the larger point is that neither before nor after accounting for pre-poll alliances, is there any evidence of any trend towards a two-party system and to the contrary, the electoral marketplace is only getting more fragmented, understandably an expression of the diversity of this democracy.

The Indian electoral democracy has often confounded most observers and justifiably so. How can one explain the complexity of why TMC allies with the BJP for three elections, with the Congress for one and will now fight one independently? Which political science framework of any mature democracy can explain why and how the Congress partners with the AIADMK in 1999 and with its bitter rival DMK in 2004 in Tamil Nadu, the sixth-largest state? Alliances with regional parties is a mere reflection of the growing federalistic nature of the country, as more regional parties display their might stemming from their confidence in fighting and winning vote share much better in their states than the national parties.

The economy is not an important election issue: To any observer of Indian elections, it is very apparent that incomes and prices have always been core issues in an election, and hence this is no surprise. Welfare economics or otherwise is an economic ideology debate. But that, prices, incomes and consumption are important to voters is evident through the copious sloganeering of most political parties over many years - subsidised rice, poverty eradication, free laptops and so on. These are economic issues and it is no myth that they are not important to a voter. Economic growth is an abstract notion to the average voter unless translated into questions about jobs, incomes, prices and so on. While it is not possible to determine the causality of these issues to electoral outcomes, the vibrant sloganeering over many decades by all the political players is reasonable evidence that these issues matter to voters.

Dynastic politics and criminals in politics angers Indian voters: If we accept, as I have argued using electoral data in various opinion editorials, that political parties are rational players in the electoral game of vote maximisation to gain power, then it is entirely plausible that neither dynastic politics nor criminal politics is a big voter issue, given the blatant indulgence in this practice by all political parties across the country - national or regional. When political parties pick candidates, it is obvious that "winnability" is the primary criterion. The BJP candidate list for 2014 is filled with new dynasts similar to the lists of the Congress, DMK, Samajwadi Party, BJD and so on, and only reiterates that it is no myth that dynastic politics is a big Indian voter issue mostly for news desks, television studios and foreign journalists. It didn't require a voter survey to conclude that these are not true issues for voters because if they were, political parties would have adapted their behaviour accordingly.

Urban and global Indians abhor the current state of polity and believe it is merely a personality aberration of politicians. We hope that as voters we have different views from what we see in our politics, which explain the plethora of opinion surveys, report cards of MPs by voters and so on. The notion that politics and politicians are a mirror to society and are mere manifestations of ourselves is either dismissed callously or avoided judiciously by our urban class. If we accept two premises: that elections in India are free and fair and a majority of voters do vote, then we have to accept that what we see is who we are. That Churchillian quote: "In functioning democracies, you often get the government you deserve" rings true even after 80 years.

(The author is founding trustee, IndiaSpend. This article first appeared in Business Standard)