How India’s Construction Workers Get Gypped Of Their Due

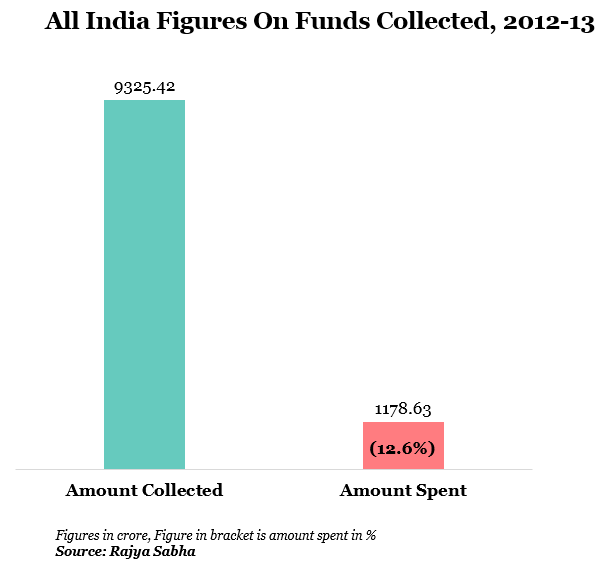

| Highlights *45 million construction workers form the country’s third largest employee base and fall in the unorganised or informal sector *Only 23% construction workers are registered with welfare boards across the country *Out of over Rs 9,300 crore collected as cess for workers welfare, only 13% (Rs 1,179 crore) has been utilised across the country |

India’s 45 million construction workers are evidently large in numbers, mostly migrant, woefully undocumented and almost totally ignored by the system at large.

Attempts have been made to fix this by providing them with some form of social security. For one, by collecting a cess from their employers, typically contractors who work for real estate developers. The money is being collected, it appears, albeit only from only a quarter of the total number who are registered. But it also appears that, even for this quarter of the workforce, this money is lying unused and not flowing back to the workers in any way.

Construction workers form the country’s third largest employee base and fall in the unorganised or informal sector. And thus are generally not covered under any Government law nor do they have any kind of job security.

The Central Government moved to correct these anomalies in 1996 when it enacted two Acts - the Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Actand the Building and Other Construction Workers’ Welfare Cess Act - to regulate the employment and conditions of service of building and other construction workers and provide for their safety, health and welfare measures.

The responsibility of collecting cess under the Building and Other Construction Workers’ Welfare Cess Act and its utilisation for welfare activities also lies with the respective welfare boards and the State Governments.

The cess is to be collected from the employer (in this case, contractors and construction companies) at the rate of 1-2% of the cost of constructionincurred by them. Contractors who are not registered with the boards will have to pay penal interest on top of the cess. The cess collecting authority (local authority or State Government) deducts upto 1% of the amount collected to meet administrative expenses.

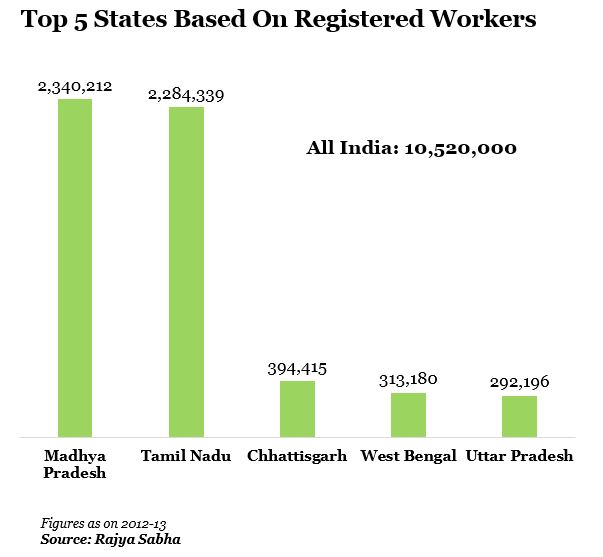

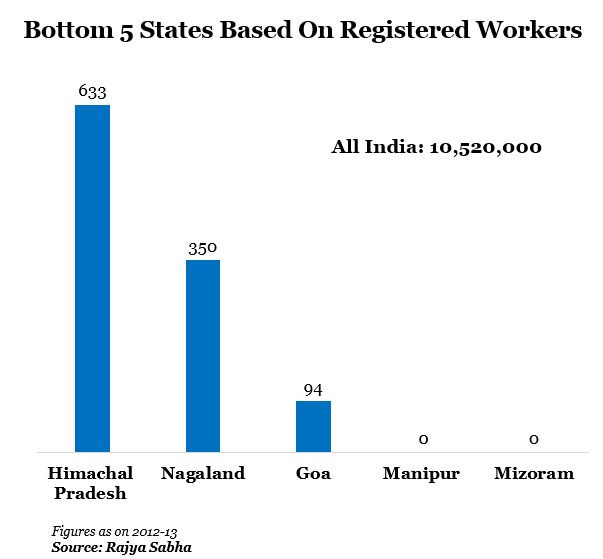

Now, a look at the broad numbers: The all-India numbers show that only 23% of the construction workers are registered with welfare boards across the country. The following table shows the top 5 states and bottom 5 states based on the number of registered construction workers:

Figure 1(a)

Figure 1(b)

The highest registration is in Madhya Pradesh with 2.34 million workers followed by Tamil Nadu with 2.28 million. North-Eastern states like Mizoram and Manipur have not registered any construction workers!

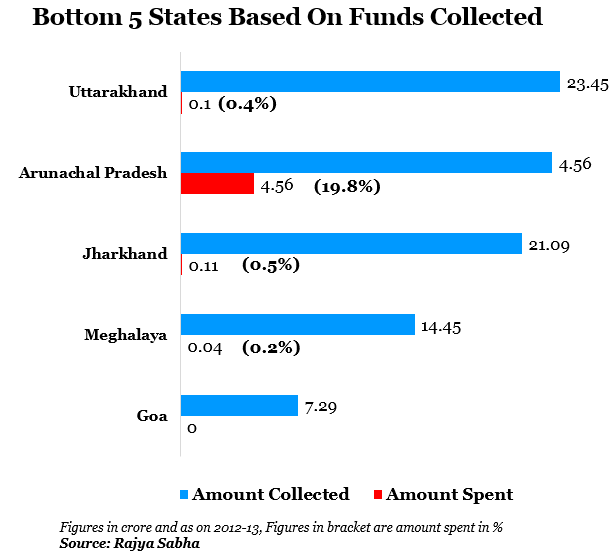

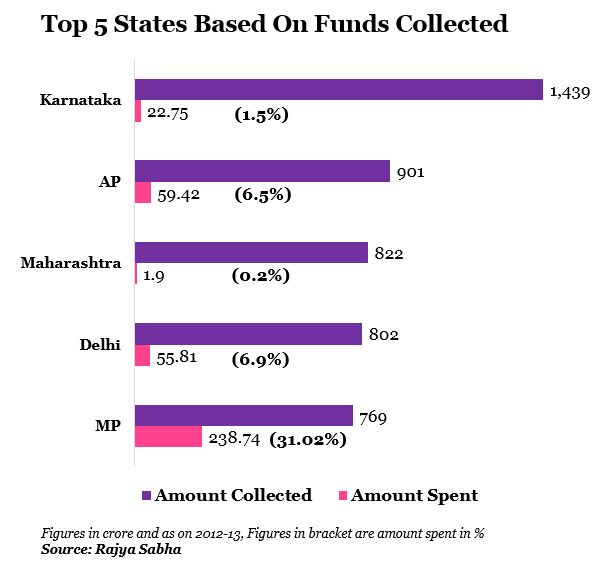

The aim of the Governments in collecting the cess is to utilise it for vocational training and skill development of construction workers and their children. The following table shows the cess collected and spent for the top 5 and bottom 5 states:

Figure 2(a)

Figure 2(b)

Figure 2(c)

The table highlights the fact that even though the amount collected is high, money spent on the welfare of workers is very low. For example, if we look at Karnataka, which has the highest amount of cess collected at Rs 1,439 crore, it has spent only Rs 22.75 crore i.e., only 1.5% of the funds have been used.

A similar story can be observed in Maharashtra where the amount collected is Rs 822 crore but the amount utilised is only Rs 1.9 crore, i.e.an utilisation rate of 0.2%. Even at the all-India level, only 13% funds are utilised while 87% of funds collected lie unutilised.

Some of the reasons highlighted by voluntary organisations like YUVA (Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action), a Mumbai-based organisation that works with the unorganised sector workers, are that workers can only be registered if they are employed for 90 days at a stretch and some casual laborers are employed on an hourly basis, which automatically excludes them from the system.

Another major reason is that contractors have to pay the cess when they register their workers, and that is a financial disincentive for them. Many contractors do not want to pay the cess and end up not registering their workers.

State Governments, on the other hand, claim that workers are not yet aware of the various schemes of the welfare boards. Some states have also pointed that the beneficiaries were not coming forward to claim their rights because most of them belonged to other states and went back to their native places once the work was complete. All this, of course, points to several larger problems than just the issue of workers not turning up to collect their benefits or get registered in the first place.

Bizarrely, another reason also seems to be that the Governments don’t know where to spend the funds on other than Central Government schemes like Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana(RSBY), which provides health insurance coverage for below poverty line (BPL) families in the unorganised sector.

RSBY, incidentally, has been selected by International Labor Organization and United Nations Development Programme as one of the 18 innovative case studies from around the world in the field of social protection.

So, the failure of the welfare boards seems to be on 2 levels – non-registration of workers and under-utilisation of funds. This only goes to show, no matter how well-planned a scheme is, if the machinery to execute is not functioning properly, it will not yield the desired results.

That sounds familiar?