Can Women’s Education Arrest India’s Declining Sex Ratio?

| Highlights * Female literacy has gone up in both rural and urban areas from 1999-2000 to 2009-10* Women employment is higher in rural areas than urban areas * Majority of Hindu and Muslim females are illiterate in rural areas |

A poor sex ratio has been often cited as one reason for the increasing number of crimes against women in India.

The country’s sex ratio, defined as the number of women per 1,000 males, in 2011 was 940, which is an improvement from 933 per 1,000 males in 2001.

The question we are asking is: can the twin forces of education and employment improve the situation at hand?

Ideally, education should help a woman figure out what is right for her while employment would give her the financial strength to make the right choice. Studies, like the one done by Aparna Mitra at the University of Oklahoma, point in that direction. And so does the data. At least, that’s what the data on some communities in India tells us.

In many parts of India, a male child is seen as being able to support businesses or agriculture or parents in their old age while girls are viewed more as an economic liability. IndiaSpend had earlier looked at the National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) data on how religious communities are placed on various parameters like income and education. And we observed that some communities were much better compared to others.

Another fact was that the status of women was better in the well-off communities. Christians and Sikhs, for instance, have the highest number of women who have studied in the secondary school and above category in both rural and urban areas. And Christians have better sex ratio compared to other communities.

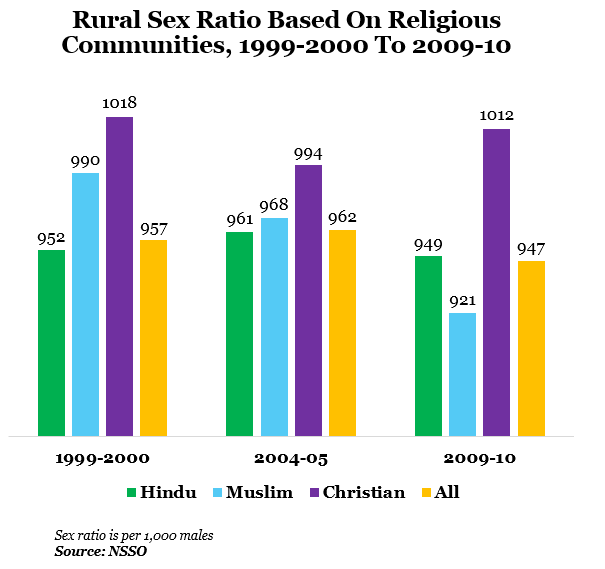

First, a look at the sex ratio of various communities since 1999-2000:

Figure 1(a)

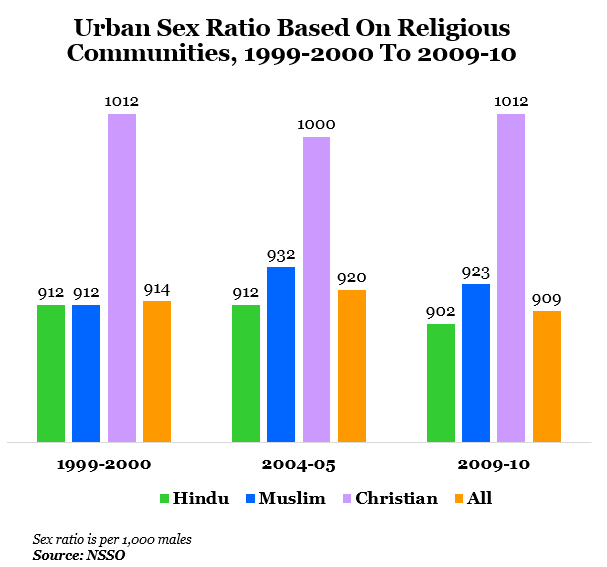

Figure 1(b)

The sex ratio has been improving among Christians over the years. For Hindus, it has come down in rural areas from 952 to 949 during 1999-2000 to 2009-10. In urban areas, it has declined from 912 to 902 in the same period.

The situation is slightly different for Muslims: the ratio declined sharply from 990 to 921 in rural areas but improved to 923 from 912 in urban areas in the same period.

So, why does a particular community do better than the others when it comes to sex ratios? We could look at education and employment numbers to explain the issue. And we could also try and analyse the link between employment and education.

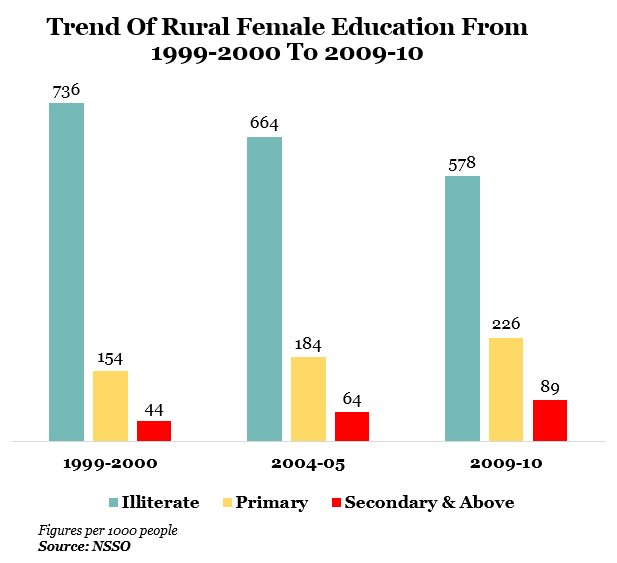

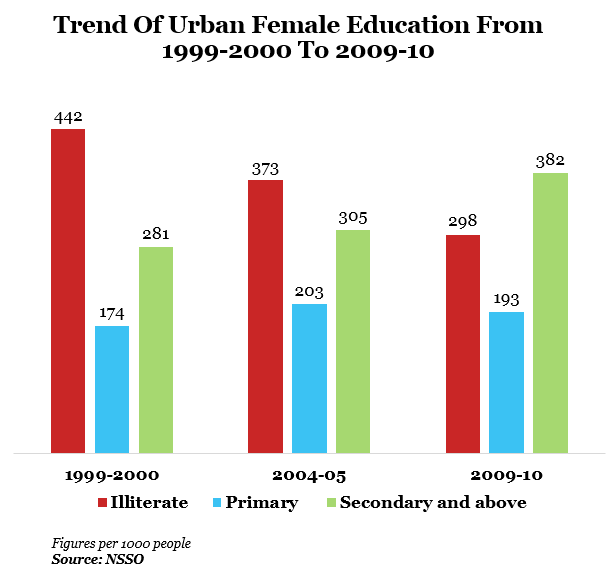

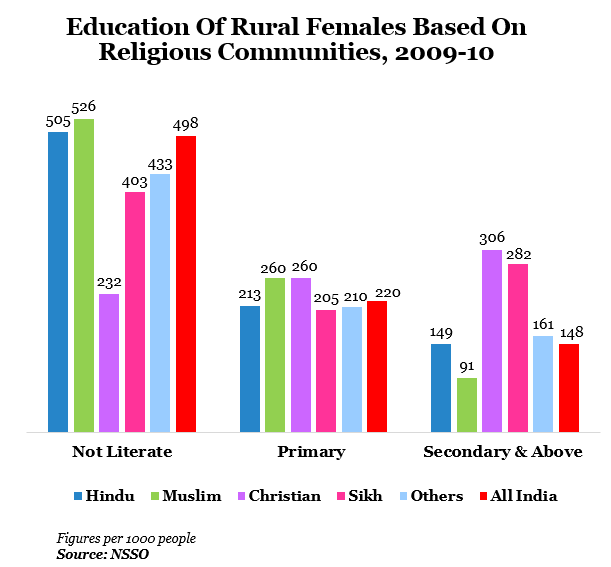

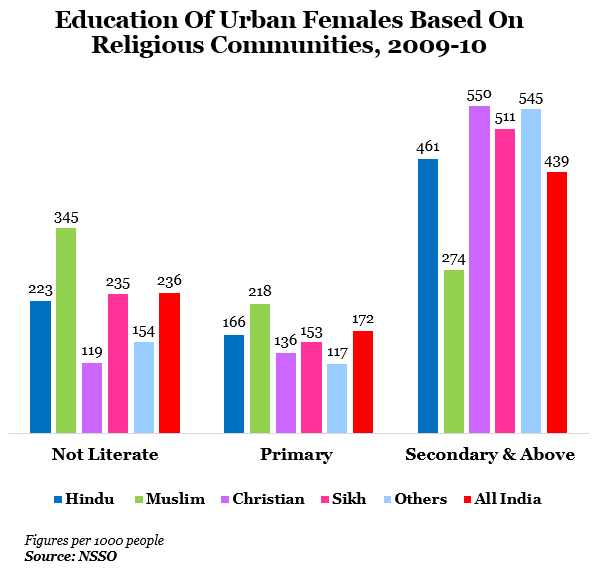

Let us first look at trends in female education from 1999-2000 to 2009-10:

Figure 2(a)

Figure 2(b)

The all-India trend shows that female literacy increased in both rural and urban areas from 1999-2000 to 2009-10. Although the numbers are much lower than their male counterparts, the highest increase was seen in the secondary school level and above for females in rural areas. Here, the numbers almost doubled from 1999-2000 to 2009-10.

The community that reported the highest increase (46%) in literacynumbers among females was Christians in rural areas. While the community that showed the highest increase in femalesaccessing primary education was Muslims with 65% in rural areas.

The Sikhs actually saw a drop of 10% during the same time period for primary education. In secondary education and above category, Sikhwomen have seen the highest increase of 81%.

In urban areas, the number of females accessing secondary education increased 35% and primary education by 11% during the same time. The highest increase in female literacy was seen among Hindu females, and there was an increase of 5.4% among Sikh women during 1999-2000 to 2009-10.

The highest increase in primary education was seen among Sikh females with 44% while Christians actually saw a drop of 17% in the same category. Muslim females have the highest percentage (54%) in the secondary and above category.

Figure 3(a)

Figure 3(b)

It can be seen that the majority of Hindu females are illiterate in rural areas while only 213 females (per 1,000 females) have studied up to the primary level. And only 149 have studied till secondary and above. If we look at the Muslim community, the situation is even bleaker with 526 females who are illiterate while 260 females study up to primary and only 91 study beyond.

The picture changes for Hindu females in urban areas where nearly 461 have studied in secondary and above. But the situation remains more or less the same for Muslim women in urban areas: they have the highest number of illiterates and also the lowest number of females who have gained secondary and above education.

But let’s look at the better-off communities like Christians and Sikhs: both communities have the lowest number of illiterates among females in rural areas. And these communities have the highest numbers in the secondary and above category in both rural and urban areas.

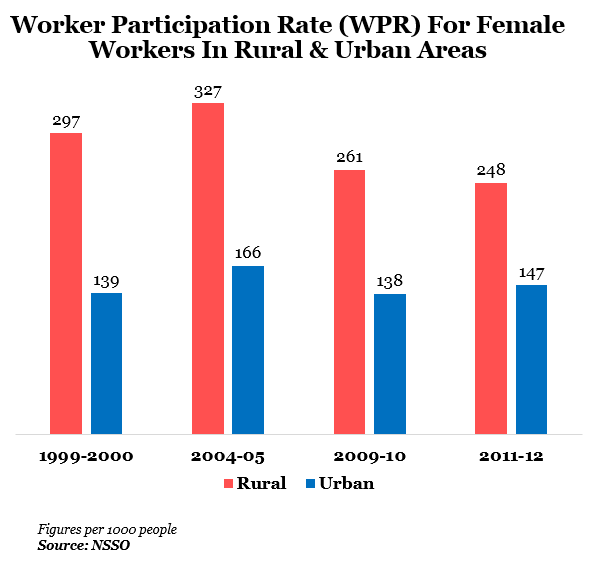

Now, let’s look at the employment data, starting with the overall numbers:

Figure 4

It can be seen that the worker participation rate (WPR), or number of females in the labour force (per 1,000 females)in rural areas is higher even though there are more number of illiterate women in rural areas. However, we can also seea decline in WPR for women in rural areas: from 327 in 2004-05, it has dropped to 248 in 2011-12.

On the other hand, the WPR of working women in urban areas presents a mixed picture: while it was 166 in 2004-05, it dropped sharply to 138 in 2009-10 only to increase again to 147 in 2011-12.

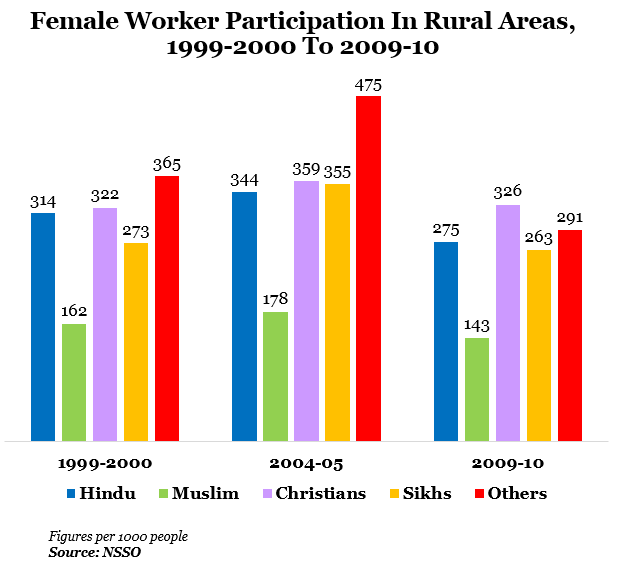

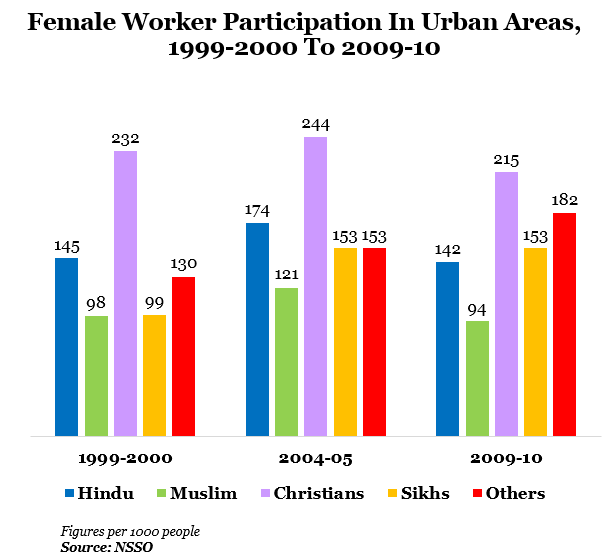

We will now look at the community-wide worker participation ratio.

Figure 5(a)

Figure 5(b)

It can be seen that the female worker participation rate has come down in rural areas for most communities, except Christians. A similar trend can be seen in urban areas as well except the ‘others’ category where it has increased. Overall, it can be seen that Christians, followed by Sikhs, have the highest number of female worker participation.

Conclusion

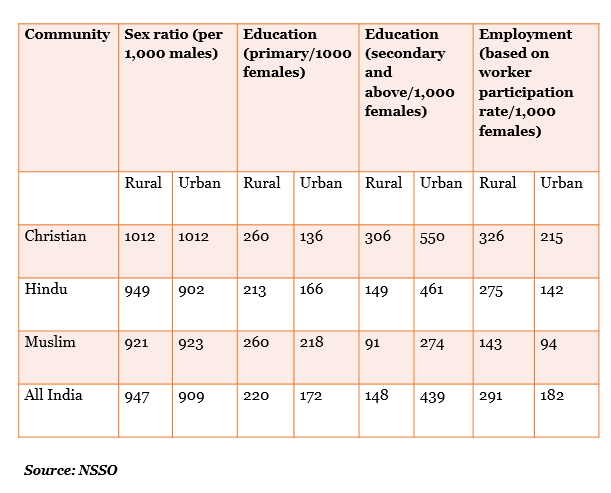

Figure 6

Communities where greater number of females are educated and have a higher worker participation rate tend to have a better sex ratio. For example, the Christian community have a better sex ratio compared to other communities. They also have the highest number of educated females in primary and secondary level in rural areas and the highest worker participation rate in both rural and urban areas.

We must, however, keep in mind that Christians and Sikhs represent only 2.3% and 1.3%, respectively, of the population.

Can the converse be true? The data does not seem to be consistent and varies with change in location (i.e. rural or urban areas). For example, for Muslims, in rural areas, the sex ratio is the lowest of all the communities at 921; with the lowest number of females educated upto the secondary level or above (91) and the lowest number of females in the workforce (143).

What is clear (at least from the reading of these sets of data) is a relationship between the improvement of sex ratio through education and greater employment. Other sociological factors, which cannot be quantified like attitudes of families and the impact of a patriarchal society, would also be playing a role.

Among the factors that policy makers should address to solve a whole lot of larger problems, education for women is clearly an important one. There is no blinding insight perhaps in this. There is, however, the price to pay. As we are only too painfully aware.